Mexico, A brief History

The International History Project

Before the Spanish arrival in 1519, Mexico was occupied by a large number of Indian groups with very different social and economic systems. In general the tribes in the arid north were relatively small groups of hunters and gatherers who roamed extensive areas of sparsely vegetated deserts and steppes. These people are often referred to as Chichimecs, though they were a mixture of several linguistically distinctive cultural groups.

In the rest of the country the natives were agriculturalists, which allowed the support of dense populations. Among these were the Maya of the Yucatan, Totonac, Huastec, Otomi, Mixtecs, Zapotecs, Tlaxcalans, Tarascans, and Aztecs. A number of these groups developed high civilizations with elaborate urban centers used for religious, political, and commercial purposes. The Mayan cities of Chichen Itza, Uxmal, and Palenque, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, Tzintzuntzan of the Tarastec, and Monte Alban of the Zapotecs are examples.

By AD 1100 the Toltecs had conquered much of central and southern Mexico and had established their capital at Tula in the Mesa Central. They also built the city of Teotihuacan near present-day Mexico City. At about the same time, the Zapotecs controlled the Oaxaca Valley and parts of the Southern Highlands. The cities they built at Mitla and Monte Alban remain, though they were taken over by the Mixtecs prior to the arrival of the Spanish.

When the Spanish arrived in central Mexico, the Aztecs controlled most of the Mesa Central through a state tribute system that extracted taxes and political servility from conquered tribal groups. The Aztecs migrated into the Mesa Central from the north and fulfilled a tribal prophesy by establishing a city where an eagle with a snake in its beak rested on a cactus. This became the national symbol of Mexico and adorns the country's flag and official seal. The Aztecs founded the city of Tenochtitlan in the early 1300s, and it became the capital of their empire. The Tlaxcalans to the east, the Tarascans on the west, and the Chichimecs in the north were outside the Aztec domain and frequently warred with them. The nation's name derives from the Aztecs' war god, Mexitli.

Spanish Conquest

From the time of Hernando Cortez's conquest until 1821, Mexico was a colony of Spain. Cortez first entered the Valley of Mexico on the Mesa Central in 1519 after marching overland from Veracruz, the town he had founded on the Gulf Coastal Plain. With fewer than 200 soldiers and a few horses, the initial conquest of the Aztecs was possible only with the assistance of the large Indian armies Cortez assembled from among the Aztecs' enemies. After a brief initial success at Tenochtitlan, the Spanish were driven from the city on the Noche Triste but returned in 1521 to destroy the city and to overwhelm the Aztecs. Within a short time the rest of central and southern Mexico and much of Central America were conquered from Mexico City.

The Spanish usurped the Indian lands and redistributed them among themselves, first as encomiendas, a system of tribute grants, and later as haciendas, or land grants. During the early contact with Indians, millions died from such European diseases as measles and smallpox, for which the natives had no immunity. Central Mexico did not regain its pre-Columbian population numbers until perhaps 1900.

Independence

Along with other Spanish colonies in the New World, Mexico fought for and gained its independence in the early 1800s. On Sept. 16, 1810, in the town of Dolores Hidalgo, the priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla rang his church's bells and exorted the local Indians to "recover from the hated Spaniards the land stolen from your forefathers. . ." This is celebrated as Mexican Independence Day. Padre Hidalgo was hanged in July 1811.

Hidalgo was succeeded by Jose Maria Morelos y Pavon, another parish priest but a more able leader than his predecessor. Morelos called a national congress, which on Nov. 6, 1812, officially declared Mexico to be independent from Spain. Morelos was executed by a Spanish firing squad in 1815, but his army, led by Vicente Guerrero, continued fighting until 1821. Because of weaknesses and political divisions in Spain, the revolutionary movement gained strength. Agustin de Iturbide, a royalist officer, joined forces with Guerrero and drafted the Plan of Iguala, which provided for national independence under a constitutional monarchy--the Mexican Empire. Not surprisingly, Iturbide was crowned emperor of Mexico in July 1822, and the newly formed empire lasted less than a year. Iturbide was exiled from the country but returned and was executed.

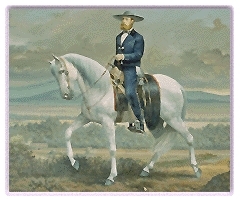

General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna then emerged as the dominant political force for some 30 years. Santa Anna was president of Mexico when Texas revolted and during the Mexican-American War of 1846.

Juarez Years

After nearly a half century of independence, Mexico had made relatively little economic or political progress, and the peasantry continued to suffer. In 1858 Benito Juarez, a Zapotec from Oaxaca, became president. He attempted to eliminate the role of the Roman Catholic church in the nation by appropriating its land and prerogatives. In 1859 the Ley Lerdo was issued--separating church and state, abolishing monastic orders, and nationalizing church property. Juarez had anticipated that Indians and peasants would reacquire the 50 percent of the nation's land formerly held by the church, but the properties were quickly purchased by the elite.

Because of the many years of economic and political chaos that had elapsed, Mexico was financially insolvent. In 1861 Juarez announced a suspension of payment on foreign loans, and the British, Spanish, and French occupied Veracruz in order to collect the Mexican debts. The British and Spanish quickly withdrew, but France overthrew the Mexican government and in 1864 declared Mexico an empire with Maximilian I of Austria as emperor. During the war with the French, the Mexican armies won a major battle on May 5, 1862, despite being severely outnumbered and underarmed. That victory is celebrated as Cinco de Mayo, a national holiday. Because of its own Civil War, the United States was unable to enforce its Monroe Doctrine, which prohibited European involvement in the Americas. At the close of the Civil War, however, the United States threatened to send troops into Mexico, and the French army withdrew from the country. Maximilian was executed by the Mexicans in 1867.

After the fall of the French and several years of turmoil, Porfirio Diaz emerged to become president in 1877 and, except for four years, ruled as an absolute dictator until 1910. During his reign Diaz encouraged foreign investment and attempted to modernize the nation. He helped to increase the GDP fivefold, expanded both exports and imports, saw gold and silver production increase from 25 million to 160 million dollars a year, and built more than 15,000 miles (24,000 kilometers) of railway. During this same period Diaz lined his pockets and gave away huge concessions of land to friends and foreign speculators. By 1910 more than 95 percent of rural families had become landless--debt peons because of government expropriation of communally held farm villages.

Mexican Revolution

Because Diaz had surrounded himself with friends and cronies who gained economic and political power, there was little opportunity for outsiders in the process even if they were upper-class Mexicans. Francisco Madero, born into a wealthy mining and ranching family of northern Mexico, is credited with instigating the Mexican Revolution. After the fraudulent election of 1910, Madero led a revolutionary movement that in 1911 captured the isolated border city of Ciudad Juarez. An old man in ill health, Diaz was forced to resign, and Madero was elected president on a platform promising social reform.

Madero was idealistic but politically inept. As a result his presidency was short-lived and chaotic. Felix Diaz, Porfirio's nephew, and Gen. Victoriano Huerta joined together in a rebellion that ousted Madero. He and his vice-president, Pino Suarez, were executed by the military in February 1913.

Huerta became president, but counterrevolutions broke out in the north. They were led by Gen. Venustiano Carranza, a follower of Madero and governor of Coahuila, with Pancho Villa and Gen. Alvaro Obregon. Peasants in the south, disillusioned with Madero's ineffectiveness, rallied behind the charismatic Indian revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. While the northern revolutionaries were largely interested in access to power, Zapata and his followers, the zapatistas, demanded land and liberty for the peasantry.

During the next few years disorder and chaos reigned. In 1915 Carranza overthrew Huerta to became president, but in the process he alienated Villa, among others. Zapata was killed shortly after Carranza came to power, but his ideal of agrarian reform became a cornerstone of the revolution. Villa returned to Chihuahua and raided border towns in the southwest- ern United States, including Columbus, N.M., where a number of Americans were killed. American Gen. John J. Pershing was sent into Mexico to capture Villa but was unsuccessful. (See also Villa, Pancho; Zapata, Emiliano.)

The major accomplishment of the Carranza period was the Constitution of 1917, which sought to destroy the feudalism that had existed in Mexico for 400 years. After Carranza's assassination in 1920, General Obregon ascended to the presidency. A strong individual, he was both willing and able to push through social reforms. His successor in 1924 was Gen. Plutarco Elias Calles, a longtime political ally. Calles was vigorously antichurch and was also unfriendly to foreign capital investment. Only through diplomatic intervention was Calles persuaded to reopen churches that had closed and to become less hostile to the foreign governments he had alienated.

Obregon was elected to a second term in 1928 but was assassinated that same year. Calles, who had founded the National Revolutionary party, the predecessor of the Institutional Revolutionary party (PRI) that still controls the nation, filled the office of interim president with three successive puppet presidents.

Peaceful Reforms

The election of Gen. Lazaro Cardenas in 1934 changed the politics of the nation. Cardenas expelled Calles and developed a vigorous six-year plan to modernize the country. He redistributed more land than did all of his predecessors combined, built rural schools, nationalized the petroleum industry and strengthened the unions.

Miguel Aleman Valdes, president from 1946 to 1952, was responsible for massive public-works projects, including irrigation schemes in the northwest and hydroelectric power in the south. Luis Echeverria Alvarez (1970-76) devalued the peso after nearly 25 years of parity with the United States dollar. Jose Lopez Portillo (1976-82) directed the frantic economic growth of the oil boom. Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado (1982-88) inherited an economy that had been transformed by a rapid decrease in international oil prices as well as huge foreign debts. In July 1988 the PRI candidate Carlos Salinas de Gortari was elected president in a vote marred by charges of widespread fraud. In 1991, President Salinas ordered the immediate closing of Mexico City's largest government-operated refinery in a move to combat the city's air-pollution crisis. The giant refinery would be replaced by public parks and green spaces. Salinas was succeeded in 1994 by Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de Leon, who was elected after the leading candidate, Luis Donaldo Colosio, was assassinated. In July 1996 Zedillo and the country's main opposition parties signed a landmark agreement toward political reform. The pact eliminated the PRI's control of election procedures and ballot counting and placed limits on campaign spending. The agreement added 17 new amendments to Mexico's constitution.

Sixty-eight years of uninterrupted legislative rule by PRI came to an end in July 1997 as Mexican voters handed control of the country's lower house of parliament to two opposition parties nominally allied against the PRI. While the PRI won the largest individual share of the vote, finishing with approximately 39 percent of the vote, it failed to win an independent majority in the lower house for the first time since 1929. The National Action party (PAN) finished second in the election, capturing 27 percent of the vote, and the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) won nearly 26 percent of the vote. Political analysts were nearly unanimous in stating that the election results indicated that the Mexican political system had begun to move away from thinly veiled one-party rule and toward genuine multiparty democracy. Nowhere was the changing political atmosphere more evident than in Mexico City, where PRD leader Cuahtemoc Cardenas Solorzano won a landslide victory in the mayoral race.

Recent Relations with the United States

Relations between the United States and Mexico fluctuated in the 20th century. A long-standing border dispute was settled in 1963, and in 1992 the two countries, along with Canada, signed the broadest trade agreement ever reached between them. The continent-wide North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect in 1994. In addition, the United States and Mexico have worked cooperatively to deal with the flow of illegal narcotics traffic from Mexico to the United States. The question of illegal The question of illegal immigration and the treatment of illegals in the United States is also a source of irritation between the nations.

Unrest in Chiapas

Tensions between pro-government paramilitary forces and the anti-government Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) exploded during the first two weeks of January in 1994, when EZLN guerrillas staged an uprising throughout Chiapas in protest against the Mexican government's treatment of Mexico's large but impoverished Indian community. The 1994 uprising left at least 140 people dead, and it sparked an ongoing struggle that raged throughout the southern state of Chiapas and claimed between 300 and 600 lives in the ensuing years. In December 1997 the village of Acteal in Chiapas became the site of one of the bloodiest massacres in recent Mexican history, as an armed paramilitary group slaughtered at least 45 people and wounded dozens more. Although the motive for the attack, as well as the identities of the perpetrators, remained unclear, villagers from Acteal suggested that pro-government guerrillas had staged the attack to retaliate for Acteal's support of the EZLN, noting that Acteal's villagers had been strong supporters of the anti-government peasant rebellion that began in Chiapas in 1994.

Before the Spanish arrival in 1519, Mexico was occupied by a large number of Indian groups with very different social and economic systems. In general the tribes in the arid north were relatively small groups of hunters and gatherers who roamed extensive areas of sparsely vegetated deserts and steppes. These people are often referred to as Chichimecs, though they were a mixture of several linguistically distinctive cultural groups.