Kush And The Eastern Mediterranean

The Rise Of Civilization In The Middle East And Africa

Edited By: R. A. Guisepi

Toward the end of the early civilization period, a number of partially

separate civilization centers sprang up on the fringes of the civilized world

in Africa and the Middle East, extending also into parts of southern Europe.

These centers built heavily on the achievements of the great early centers.

They resulted from the expansion efforts of these centers, as in the Egyptian

push southward during the New Kingdom period and from new organizational

problems within the chief centers themselves; in the Middle East, separate

societies emerged during the chaotic centuries following the collapse of the

Hittite empire.

Kush And Axum: Civilization Spreads In Africa

The kingdom of Kush sprang up along the upper (southern) reaches of the

Nile. Kush was the first African state other than Egypt of which there is

record. This was a state on the frontiers of Egyptian activity, where Egyptian

garrisons had been stationed from time to time. By 1000 B.C. it emerged as an

independent political unit, though strongly influenced by Egyptian forms. By

730 B.C., as Egypt declined, Kush was strong enough to conquer its northern

neighbor and rule it for several centuries, though this conquest was soon

ended by Assyrian invasion from the Middle East. After this point the Kushites

began to push their frontiers farther south, gaining a more diverse African

population and weakening the Egyptian influence. It was at this point that the

new capital was established at Meroe. Kushites became skilled in iron use and

had access to substantial African ore and fuel. The use of iron tools extended

the area that could be brought into agriculture. Kush formed a key center of

metal technology in the ancient world, as a basis of both military and

economic strength.

Kushites developed a form of writing derived from Egyptian hieroglyphics

(and which has not yet been fully deciphered). They established a number of

significant cities. Their political organization, also derived from Egypt,

emphasized a strong monarchy with elaborate ceremonies based on the belief

that the king was a god. Kushite economic influence extended widely in

sub-Saharan Africa. Extensive trade was conducted with people to the west, and

this trade may have brought knowledge of iron making to much of the rest of

Africa. The greatest period of the kingdom at Meroe, where activities centered

from the early 6th century onward, lasted from about 250 B.C. to A.D. 50. By

this time the kingdom served as a channel for African goods - animal skins,

ebony and ivory, gold and slaves - into the commerce of the Middle East and

the Mediterranean. Many monuments were built during these centuries, including

huge royal pyramids and an elaborate palace in Meroe. Much fine pottery and

jewelry were produced. Meroe began to decline from about A.D. 100 onward and

was defeated by a kingdom to the south, Axum, around A.D. 300. Prosperity and

extensive political and economic activity did not end in this region, but

extended into the formation of a kingdom in present-day Ethiopia.

The outreach of Kush is not entirely clear beyond its trading network set

up with neighboring regions. Whether African peoples outside the Upper Nile

region learned much from Kush about political forms is unknown. Certainly

there was little imitation of its writing, and the region of Kush and Ethiopia

would long remain somewhat isolated from the wider stream of African history.

Nevertheless, the formation of a separate society stretching below the eastern

Sahara was an important step in setting the bases for technological and

economic change throughout much of upper Africa. Though its achievements flow

less fully into later African development, Kush holds for Africa what Sumer

achieved for the Middle East - it set a wider process of civilization in

motion.

The Mediterranean Region

Smaller centers in the Middle East began to spring up after about 1500

B.C. Though dependent on the larger Mesopotamian culture for many features,

these centers added important new ingredients and in some cases also extended

the hold of civilization westward to the Asian coast of the Mediterranean. The

smaller cultures also added to the diversity of the Middle East, creating a

varied array of identities that would continue to mark the region even under

the impetus of later empires, such as Rome, or the sweeping religion of Islam.

Several of these smaller cultures proved immensely durable and would influence

other parts of the world as well.

The Jews

The most important of the smaller Middle Eastern groups were the Jews,

who gave the world one of its most influential religions. The Jews were a

Semitic people (a population group that also includes the Arabs). They were

influenced by Babylonian civilization but also marked by a period of

enslavement in Egypt. They settled in the southeast corner of the

Mediterranean around 1600 B.C., probably migrating from Mesopotamia. Some

moved into Egypt where they were treated as a subject people. In the 13th

century B.C., Moses led these Jews to Palestine, in search of a homeland

promised by the Jewish God, Yahweh. This was later held to be the central

development in Jewish history. The Jews began at this point to emerge as a

people with a self-conscious culture and some political identity. At most

points, however, the Jewish state was small and relatively weak, retaining

independence only while other parts of the Middle East were disorganized. A

few Jewish kings were able to unify their people, but at many points the Jews

were divided into separate regional states. Most of Palestine came under

foreign (initially Assyrian) domination from 722 B.C. onward, but the Jews

were able to maintain their cultural identity and key religious traditions.

Monotheism

The distinctive achievement of the Jews was the development of a strong

monotheistic religion. Early Jewish leaders probably emphasized a particularly

strong, creator god as the most powerful of many divinities - a hierarchy not

uncommon in animism - but this encouraged a focus on the father God for prayer

and loyalty. By the time of Moses, Jews were urged increasingly to abandon

worship of all other gods and to receive from Yahweh the Torah (a holy Law),

the keeping of which would assure divine protection and guidance. From this

point onward Jews regarded themselves as a chosen people under God's special

guidance. As Jewish politics deteriorated due to increasing foreign pressure,

prophets sprang up to call Jews back to faithful observance of God's laws. By

the 9th century B.C. some religious ideas and the history of the Jews began to

be written down in what would become the Jewish Bible (the Old Testament of

the Christian Bible).

Besides the emphasis on a single God, Jewish religion had two important

features. First was the idea of an overall divine plan. God guided Jewish

history, and when disasters came they constituted punishment for failures to

live up to divine laws. Second was the concept of a divinely organized

morality. The Jewish God demanded not empty sacrifices or selfish prayers, but

righteous behavior. God, though severe, was ultimately merciful and would help

the Jews to regain morality. This system was not only monotheistic but also

intensely ethical; God was actively concerned with the doings of people and so

enjoined good behavior. By the 2d century B.C., these concepts were clearly

spelled out in the Torah and the other writings that were formed into the Old

Testament of the Bible. By their emphasis on a written religion the Jews were

able to retain their identity under foreign rule and even under outright

dispersion from their Mediterranean homeland.

The impact of Jewish religion beyond the Jewish people was complex. The

Jews saw God's guidance in all of human history, and not simply their own.

Ultimately all peoples would be led to God. But God's special pact was with

the Jews, and there was little premium placed on missionary activity or

converting others to the faith. This limitation helps explain the intensity

and durability of the Jewish faith; it also kept the Jewish people a minority

within the Middle East though at various points substantial conversions to

Judaism did spread the religion somewhat more widely. Jewish monotheism,

though a landmark in world religious history, is noteworthy for sustaining a

distinctive Jewish culture to our own day, not for immediately altering a

wider religious map.

Yet the elaboration of monotheism had a wide significance. In Jewish

hands the concept of God became less humanlike, more abstract - a basic change

not only in religion but in overall outlook. Yahweh had a power and a planning

quality far different from the attributes of the traditional gods of the

Middle East or Egypt. The gods, particularly in Mesopotamia, were whimsical

and capricious; Yahweh was orderly and just, and individuals could know what

to expect if they adhered to God's rules. The link to ethical conduct and

moral behavior was also central. Religion for the Jews was a system of life,

not merely a set of rituals and ceremonies. The full impact of this religious

transformation on Middle Eastern and Mediterranean civilization would come

only later, when Jewish ideas were taken up by the proselytizing faiths of

Christianity and Islam. But the basic concept formed one of the legacies of

the twilight period from the first great civilizations to the new cultures

that would soon arise in their place.

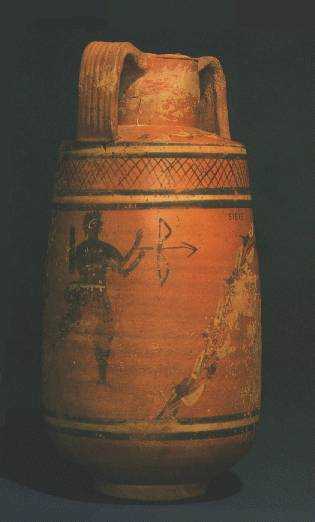

The Minoans

The Jews were not alone among the distinct societies popping up in the

eastern Mediterranean. Around 1600 B.C. a civilized society developed on the

island of Crete. This Minoan society traded widely with both Mesopotamia and

Egypt, and probably acquired many of its civilized characteristics from this

exchange. Minoan society, for example, copied Egyptian architectural forms and

mathematics, though it developed important new artistic styles in the colossal

palace built in the capital city, Knossos. The alphabet, too, was adapted from

Egypt. Political structures similar to those of Egypt or the Mesopotamian

empires emphasized elaborate bureaucratic con- trols, complete with massive

record keeping, under a powerful monarch. Minoan navies at various points

conquered parts of the mainland of Greece, eventually leading to the

establishment of the first civilization there. Centered particularly in the

kingdom of Mycenae, this early Greek civilization developed considerable

capacity for monumental building, and also conducted important wars with

city-states in the Middle East, including the famous conflict with Troy.

Civilizations in Crete and in Greece were overturned by a wave of

Indo-European invasions, culminating around 1000 B.C., that temporarily

reduced the capacities of these societies to maintain elaborate art or

writing, or extensive political or economic organizations. While the

civilization that would arise later, to form classical Greece, had somewhat

separate origins, it would build extensively on the memories of this first

civilized society and on its roots in Egyptian and Mesopotamian achievements.

The Phoenicians

Another distinct society grew up in the Middle East itself, in what is

now the nation of Lebanon. Around 2000 B.C. a people called the Phoenicians

settled on the Mediterranean coast. Like the Minoans, they quickly turned to

seafaring because their agricultural hinterland was not extensive. The

Phoenicians used their elaborate trading contacts to gain knowledge from the

major civilization centers, and then in several key cases improved upon what

they learned. Around 1300 B.C. they devised a much simplified alphabet based

on the Mesopotamian cuneiform. The Phoenician alphabet had only 22 letters,

and so was learned relatively easily. It served as ancestor to the Greek and

Latin lettering systems. The Phoenicians also upgraded the Egyptian numbering

system.

The Phoenicians were, however, a merchant people, not vested in extensive

cultural achievements. They advanced manufacturing techniques in several

areas, particularly the production of dyes for cloth. Above all, for

commercial purposes, they dispersed and set up colonies at a number of points

along the Mediterranean. They benefited from the growing weakness of Egypt and

the earlier collapse of Minoan society and its Greek successor, for there were

few competitors for influence in the Mediterranean by 1000 B.C. Phoenician

sailors moved steadily westward, setting up a major trading city on the coast

of North Africa at Carthage, and lesser centers in Italy, Spain, and southern

France. The Phoenicians even traded along the Atlantic coast of Europe,

reaching Britain where they sought a supply of tin. Ultimately Phoenicia

collapsed in the wake of the Assyrian invasions of the Middle East, though

several of the colonial cities long survived.