Holy Roman Empire, The

Book: Chapter I: Introductory.

Author: Bryce, James

Page One

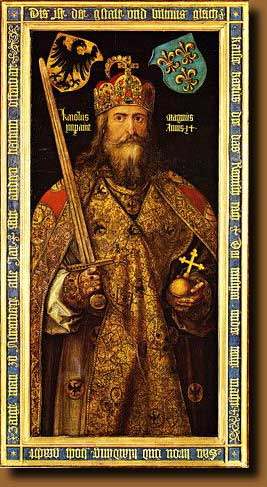

From Christmas Day in AD 800 until Aug. 6, 1806, there existed in Europe a peculiar political institution called the Holy Roman Empire. The name of the empire as it is known today did not come into general use until 1254. It has truly been said that this political arrangement was not holy, or Roman, or an empire. Any holiness attached to it came from the claims of the popes in their attempts to assert religious control in Europe. It was Roman to the extent that it tried to revive, without success, the political authority of the Roman Empire in the West as a countermeasure to the Byzantine Empire in the East. It was an empire in the loosest sense of the word--at no time was it able to consolidate unchallenged political control over the vast territories it pretended to rule. There was no central government, no unity of language, no common system of law, no sense of common loyalty among the many states within it. Over the centuries the empire's boundaries shifted and shrank drastically.

Chapter I: Introductory.

Of those who in August, 1806, read in the English newspapers that the

Emperor Francis II had announced to the Diet his resignation of the imperial

crown, there were probably few who reflected that the oldest political

institution in the world had come to an end. Yet it was so. The Empire which

a note issued by a diplomatist on the banks of the Danube extinguished, was

the same which the crafty nephew of Julius had won for himself, against the

powers of the East, beneath the cliffs of Actium; and which had preserved

almost unaltered, through eighteen centuries of time, and through the greatest

changes in extent, in power, in character, a title and pretensions from which

all meaning had long since departed. Nothing else so directly linked the old

world to the new - nothing else displayed so many strange contrasts of the

present and the past, and summed up in those contrasts so much of European

history. From the days of Constantine till far down into the middle ages it

was, conjointly with the Papacy, the recognised centre and head of

Christendom, exercising over the minds of men an influence such as its

material strength could never have commanded. It is of this influence and of

the causes that gave it power rather than of the external history of the

Empire, that the following pages are designed to treat. That history is

indeed full of interest and brilliancy, of grand characters and striking

situations. But it is a subject too vast for any single canvas. Without a

minuteness of detail sufficient to make its scenes dramatic and give us a

lively sympathy with the actors, a narrative history can have little value and

still less charm. But to trace with any minuteness the career of the Empire,

would be to write the history of Christendom from the fifth century to the

twelfth, of Germany and Italy from the twelfth to the nineteenth; while even a

narrative of more restricted scope, which should attempt to disengage from a

general account of the affairs of those countries the events that properly

belong to imperial history, could hardly be compressed within reasonable

limits. It is therefore better, declining so great a task, to attempt one

simpler and more practicable though not necessarily inferior in interest; to

speak less of events than of principles, and endeavour to describe the Empire

not as a State but as an Institution, an institution created by and embodying

a wonderful system of ideas. In pursuance of such a plan, the forms which the

Empire took in the several stages of its growth and decline must be briefly

sketched. The characters and acts of the great men who founded, guided, and

overthrew it must from time to time be touched upon. But the chief aim of the

treatise will be to dwell more fully on the inner nature of the Empire, as the

most signal instance of the fusion of Roman and Teutonic elements in modern

civilization: to shew how such a combination was possible; how Charles and

Otto were led to revive the imperial title in the West; how far during the

reigns of their successors it preserved the memory of its origin, and

influenced the European commonwealth of nations.

Strictly speaking, it is from the year 800 A.D., when a King of the

Franks was crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III, that the beginning

of the Holy Roman Empire must be dated. But in history there is nothing

isolated, and just as to explain a modern Act of Parliament or a modern

conveyance of lands we must go back to the feudal customs of the thirteenth

century, so among the institutions of the Middle Ages there is scarcely one

which can be understood until it is traced up either to classical or to

primitive Teutonic antiquity. Such a mode of inquiry is most of all needful

in the case of the Holy Empire, itself no more than a tradition, a fancied

revival of departed glories. And thus, in order to make it clear out of what

elements the imperial system was formed, we might be required to scrutinize

the antiquities of the Christian Church; to survey the constitution of Rome in

the days when Rome was no more than the first of the Latin cities; nay, to

travel back yet further to that Jewish theocratic policy whose influence on

the minds of the mediaeval priesthood was necessarily so profound.

Practically, however, it may suffice to begin by glancing at the condition of

the Roman world in the third and fourth centuries of the Christian era. We

shall then see the old Empire with its scheme of absolutism fully matured; we

shall mark how the new religion, rising in the midst of a hostile power, ends

by embracing and transforming it; and we shall be in a position to understand

what impression the whole huge fabric of secular and ecclesiastical government

which Roman and Christianity had piled up made upon the barbarian tribes who

pressed into the charmed circle of the ancient civilization.