The Great Depression

The story of the World Wide Great Depression and how it effected the 20th Century

The Twentieth Century In World History

Book: One-Half Century Of Crisis, 1914-1945

Author: Adas, Michael

Date: 1992

The Great Depression

The next step in a mounting spiral of international crisis came with the

onset of a global economic depression, which hit the headlines with the crash

of key Western banks in 1929 but which in fact had begun, sullenly, in many

parts of the world economy even earlier.

The depression resulted from new problems in the industrial economy of

Europe and the United States, combined with the long-term weakness in

economies, like those of Latin America, that depended on sales of cheap

exports in the international market. The result was a worldwide collapse that

spared only a few economies and brought political and economic pressures on

virtually every society.

Causation

The impact of the First World War on the European economy had led to

several rocky years into the early 1920s. War-induced inflation was a

particular problem in Germany, as prices soared daily and ordinary purchases

required huge quantities of currency. Forceful government action finally

resolved this crisis in 1923, but only by a massive devaluation of the mark,

which did nothing to restore lost savings. More generally, a sharp, brief

recession in 1920 and 1921 had reflected other postwar dislocations, though by

1923 production levels had regained or surpassed prewar levels. Great Britain,

an industrial pioneer that was already victim of a loss of dynamism before the

war, recovered more slowly, in part because of its unusually great dependence

on an export market now open to wider competition.

Structural problems affected other areas of Europe besides Britain and

lasted well beyond the predictable readjustments to peacetime. Farmers

throughout much of the Western world including the United States faced almost

chronic overproduction of food and resulting low prices. Food production had

soared in response to wartime needs, and then during postwar inflation many

farmers, both in western Europe and in North America, borrowed heavily to buy

new equipment, overconfident that their good markets would be sustained. But

rising European production combined with large imports from the Americas sent

prices down, which made debts harder to repay. One response was continued

flight from the countryside, as urbanization continued. Remaining farmers were

hard-pressed and unable to sustain high demand for manufactured goods.

Thus, although economies in nations such as France and Germany seemed to

have recovered by 1925, there were continued problems: the fears inflation had

generated, which in turn limited the capacity of governments to respond to

other problems, plus the weaknesses in the buying power of key groups. In this

situation, part of the mid- decade prosperity rested on exceedingly fragile

grounds. Loans from United States banks to various European enterprises helped

sustain demand for goods, but on condition that additional loans pour in to

help pay off the resultant debts.

Furthermore, most of the dependent areas in the world economy, colonies

and noncolonies alike, were suffering badly. Pronounced tendencies toward

overproduction developed in the smaller nations of eastern Europe, which sent

agricultural goods to western Europe, as well as among tropical producers in

Africa and Latin America. Here, continued efforts to win export revenue drove

local estate owners to drive up output in such goods as coffee, sugar, and

rubber. As European governments and businessmen organized their African

colonies for more profitable exploitation, they set up large estates devoted

to goods of this type. Again, production frequently exceeded demand, which

drove prices and earnings down not only in Africa but also in Latin America.

This meant in turn that many colonies and dependent economies were unable to

buy many industrial exports, which weakened demand for Western products

precisely when output tended to rise amid growing United States and Japanese

competition.

Governments of the leading industrial nations provided scant leadership

during the emerging crisis of the 1920s. Knowledge of economics was often

feeble amid a Western leadership group not noteworthy for its quality even in

more conventional areas. Nationalistic selfishness predominated. Western

nations were more concerned about insisting on repayment of any debts owed to

them or about constructing tariff barriers to protect their own industries

than in facilitating balanced world economic growth. Protectionism, in

particular, as practiced even by traditionally free-trade Great Britain and by

the many new nations in eastern Europe, simply reduced market opportunities

and made a bad situation worse. By the later 1920s employment in key export

industrial sectors in the West - coal (also beset by new competition from

imported oil), iron, and textiles - began to decline, the foretaste of more

general collapse.

The Debacle

The formal advent of depression occurred in October 1929, when the New

York stock market crashed. Stock values tumbled, as investors quickly lost

confidence in issues that had been pushed ridiculously high. United States

banks, which had depended heavily on their stock investments, rapidly echoed

the financial crisis, and many institutions failed, dragging their depositors

along with them. Even before this collapse, Americans had begun to call back

earlier loans to Europe. Yet the European credit structure depended

extensively on American loans, which had fueled some industrial expansion but

also less productive investments such as German reparation payments and the

construction of fancy town halls and other amenities. In Europe, as in the

United States, many commercial enterprises existed on the basis not of real

production power but of continued speculation. When one piece of the

speculative spiral was withdrawn, the whole edifice quickly collapsed. Key

bank failures in Austria and Germany followed the American crisis. Throughout

most of the industrial West, investment funds dried up as creditors went

bankrupt or tried to pull in their horns.

With investment receding, industrial production quickly began to fall,

beginning in the industries that produced capital goods and extending quickly

to consumer products fields. Falling production - levels dropped by as much as

one-third by 1932 - meant falling employment and lower wages, which in turn

withdrew still more demand from the economy and led to further hardship. The

existing weakness of some markets, such as the farm sector or the

nonindustrial world, was exacerbated as demand for foods and minerals

plummeted. New and appalling problems developed among workers - now out of

jobs or suffering from reduced hours and reduced pay - as well as the middle

classes. The depression, in sum, fed on itself, growing steadily worse from

1929 to 1933. Even countries initially less hard hit, such as France and

Italy, saw themselves drawn into the vortex by 1931.

In itself, the Great Depression was not entirely unprecedented. Previous

periods had seen slumps triggered by bank failures and overspeculation,

yielding several years of falling production, unemployment, and real hardship.

But the intensity of the Great Depression had no precedent in the brief

history of industrial societies. Its duration was also unprecedented; in many

countries full recovery came only after a decade, and only with the forced

production schedules provoked by World War II. The depression was also more

marked than its antecedents because it came on the heels of so much other

distress - the economic hardships of war, for example, and the catastrophic

inflation of the 1920s - and because it caught most governments utterly

unprepared to cope.

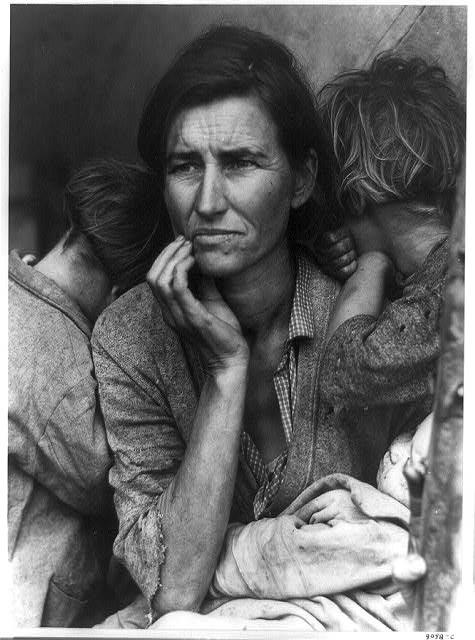

The depression was more, of course, than an economic event. It reached

into countless lives, creating hardship and tension that would be recalled

even as the crisis itself eased. Loss of earnings, loss of work, or simply

fears that loss would come could devastate people at all social levels. The

suicides of ruined investors in New York were paralleled by the vagrants'

camps and begging that spread among displaced workers. The statistics were

grim: up to one-third of all blue-collar workers in the West lost their jobs

for prolonged periods. White-collar unemployment, though not quite as severe,

was also unparalleled. In Germany 600,000 of four million white-collar workers

had lost their jobs by 1931. Graduating students could not find work or had to

resort to jobs they regarded as insecure or demeaning. Figures of six million

overall unemployed in Germany and 22 percent of the labor force unemployed in

Britain were statistics of stark misery and despair. Families were disrupted,

as men felt emasculated at their inability to provide and women and children

were disgusted at authority figures whose authority was now hollow. In some

cases wives and mothers found it easier to gain jobs in a low-wage economy

than their husbands did, and although this development had some promise in

terms of new opportunities for women, it could also be confusing for standard

family roles. Again, the agony and personal disruption of the depression

constituted no short shock. For many it was desperately prolonged, with

renewed recession around 1937 and with unemployment still averaging ten

percent or more in many countries by 1939.

Just as World War I had been, the depression was an event that blatantly

contradicted the optimistic assumptions of the later 19th century. To many, it

showed the fragility of any idea of progress, any belief that Western

civilization was becoming more humane. To still more it challenged the notion

that standard Western governments - the parliamentary democracies - were able

to control their own destinies. And because it was a second catastrophic event

within a generation, the depression led to even more extreme results than the

war itself had done - more bizarre experiments, more paralysis in the face of

deepening despair.

Worldwide Impact

Just as the depression had been caused by a combination of specifically

Western problems and wider weaknesses in the world economy, so its effects had

both Western twists and international repercussions.

A few economies were buffered from the depression. The Soviet Union, busy

building an industrial society under communist control, had cut off all but

the most insignificant economic ties with other nations under the heading

"socialism in one country." The result placed great hardships on many Russian

people, called to sustain rapid industrial development without outside

capital, but it did prevent anything like a depression during the 1930s.

Soviet leaders pointed with pride to the lack of serious unemployment and

steadily rising production rates, in a telling contrast with the miseries of

Western capitalism at the time.

For most of the rest of the world, however, the depression worsened an

already bleak economic picture. Western markets could absorb fewer commodity

imports as production fell and incomes dwindled. Hence the nations that

produced foods and raw materials saw prices and earnings drop even more than

before. Unemployment rose rapidly in the export sectors of the Latin American

economy, creating a major political challenge not unlike that faced by the

Western leaders.

Japan, as a new industrial country still heavily dependent on export

earnings for financing its imports of essential fuel and raw materials, was

hit hard too. The Japanese silk industry, an export staple, was already

suffering from the advent of artificial silk-like fibers produced by Western

chemical giants. Now luxury purchases collapsed, leading to severe

unemployment and, again, a crucial political crisis.

Between 1929 and 1931, the value of Japanese exports plummeted by 50

percent. Workers' real income dropped by almost one-third, and there were over

three million unemployed. Depression was compounded by bad harvests in several

regions, leading to rural begging and near-starvation.

The Great Depression, though most familiar in its Western dimensions, was

a truly international collapse, a sign of the tight bonds and serious

imbalances that had developed in world trading patterns. The results of the

collapse, and particularly the varied responses to it, are best traced in

individual cases. For Latin America, the depression marked a pronounced

stimulus to new kinds of effective political action, and particularly greater

state involvement in planning and direction. New government vigor did not cure

the economic effects of the depression, which escaped the control of most

individual states, but it did set an important new phase in the civilization's

political evolution. For Japan, the depression increased suspicions of the

West and helped promote new expansionism designed among other things to win

more assured markets in Asia. In the West the depression led to new welfare

programs that stimulated demand and helped restore confidence, but it also led

to radical social and political experiments such as German Nazism. What was

common in this welter of reactions was the intractable global quality of the

depression itself, which made it impossible for any purely national policy to

restore full prosperity. Even Nazi Germany, which boasted of regaining full

employment, continued to suffer from low wages and other dislocations aside

from its obvious and growing dependence on military production.

The reactions to the depression, including a sense of weakness and

confusion in many quarters inside and outside policy circles, finally helped

to bring the final great crisis of the first half of the 20th century: a

second, and more fully international, world war.