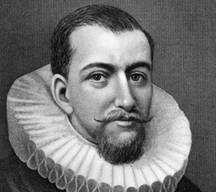

Henry Hudson Explores The Hudson River

Author: Cleveland, Henry R.

Henry Hudson Explores The Hudson River

1609

Although Henry Hudson was not the first discoverer of the waters to which

his name was given, he was a bold sailor whose achievements justly gave him

rank with the foremost navigators and explorers of his time. He was well

versed in scientific navigation. His first recorded voyage was made in the

service of the Muscovy or Russia Company of England in 1607. His object was

to find a passage across the north pole to the Spice Islands (Moluccas), in

the Malay Archipelago. Though failing in this purpose, he reached a higher

latitude than had before been attained by any navigator.

His next venture (1608), for the same company, was for "finding a passage

to the East Indies by the northeast," but he failed to pass in that direction

beyond Nova Zembla, and returned to England. These two failures discouraged

the Muscovy Company, but did not daunt Henry Hudson. Again he determined to

sail the northern seas, and the story of his third great voyage and its

results is here given to the reader.

Hudson, whose mind was completely bent upon making the discovery which he

had undertaken, now sought employment from the Dutch East India Company. The

fame of his adventures had already reached Holland, and he had received from

the Dutch the appellations of the bold Englishman, the expert pilot, the

famous navigator. The company were generally in favor of accepting the offer

of his services, though the scheme was strongly opposed by Balthazar

Moucheron, one of their number, who had some acquaintance with the arctic

seas. They accordingly gave him the command of a small vessel, named the Half

Moon, with a crew of twenty men, Dutch and English, among whom was Robert

Juet, who had accompanied him as mate on his second voyage. The journal of

the present voyage, which is published in Purchas' Pilgrims, was written by

Juet.

He sailed from Amsterdam March 25, 1609, and doubled the North Cape in

about a month. His object was to pass through the Vaygats, or perhaps to the

north of Nova Zembla, and thus reach China by the northeast passage. But

after contending for more than a fortnight with head winds, continual fogs,

and ice, and finding it impossible to reach even the coast of Nova Zembla, he

determined to abandon this plan, and endeavor to discover a passage by the

northwest. He accordingly directed his course westerly, doubled the North

Cape again, and in a few days saw a part of the western coast of Norway, in

the latitude of 68 degrees. From this point he sailed for the Faroe Islands,

where he arrived about the end of May.

Having replenished his water-casks at one of these islands he again

hoisted sail, and steered southwest, in the hope of making Buss Island, which

had been discovered by Sir Martin Frobisher, in 1578, as he wished to

ascertain if it was correctly laid down on the chart. As he did not succeed

in finding it, he continued this course for nearly a month, having much severe

weather and a succession of gales, in one of which the foremast was carried

away. Having arrived at the 45th degree of latitude, he judged it best to

shape his course westward, with the intention of making Newfoundland. While

proceeding in this direction he one day saw a vessel standing to the eastward,

and wishing to speak her he put the ship about and gave chase; but finding as

night came on that he could not overtake her he resumed the westerly course

again.

On July 2nd he had soundings on the Grand Bank of Newfoundland, and saw a

whole fleet of Frenchmen fishing there. Being on soundings for several days

he determined to try his luck at fishing; and the weather falling calm he set

the whole crew at work to so much purpose that, in the course of the morning,

they took between one and two hundred very large cod. After two or three days

of calm the wind sprang up again, and he continued his course westward till

the 12th, when he first had sight of the coast of North America. The fog was

so thick, however, that he did not venture nearer the coast for several days;

but at length, the weather clearing up, he ran into a bay at the mouth of a

large river, in the latitude of 44 degrees. This was Penobscot Bay, on the

coast of Maine.

He already had some notion of the kind of inhabitants he was to find

here, for a few days before he had been visited by six savages, who came on

board in a very friendly manner and ate and drank with him. He found that

from their intercourse with the French traders they had learned a few words of

their language. Soon after coming to anchor he was visited by several of the

natives, who appeared very harmless and inoffensive; and in the afternoon two

boats full of them came to the ship, bringing beaver-skins and other fine

furs, which they wished to exchange for articles of dress. They offered no

violence whatever, though we find in Juet's journal constant expressions of

distrust, apparently without foundation.

They remained in this bay long enough to cut and rig a new foremast, and

being now ready for sea the men were sent on shore upon an expedition that

disgraced the whole company. What Hudson's sentiments or motives with regard

to this transaction were we can only conjecture from a general knowledge of

his character, as we have no account of it from himself. But it seems highly

probable that, if he did not project it, he at least gave his consent to its

perpetration. The account is in the words of Juet, as follows: "In the

morning we manned our scute with four muskets and six men, and took one of

their shallops and brought it aboard. Then we manned our boat and scute with

twelve men and muskets, and two stone pieces, or murderers, and drave the

salvages from their houses, and took the spoil of them, as they would have

done us." After this exploit they returned to the ship and set sail

immediately. It does not appear from the journal that the natives had ever

offered them any harm or given any provocation for so wanton an act. The

writer only asserts that they would have done it if they could. No plea is

more commonly used to justify tyranny and cruelty than the supposed bad

intentions of the oppressed.

He now continued southward along the coast of America. It appears that

Hudson had been informed by his friend, Captain John Smith, that there was a

passage to the western Pacific Ocean south of Virginia, and that, when he had

proved the impossibility of going by the northeast, he had offered his crew

the choice either to explore this passage spoken of by Captain John Smith or

to seek the northwest passage by going through Davis Strait. Many of the men

had been in the East India service, and in the habit of sailing in tropical

climates, and were consequently very unwilling to endure the severities of a

high northern latitude. It was therefore voted that they should go in search

of the passage to the south of Virginia.

In a few days they saw land extending north, and terminating in a

remarkable headland, which he recognized to be Cape Cod. Wishing to double

the headland, he sent some of the men in the boat to sound along the shore,

before venturing nearer with the ship. The water was five fathoms deep within

bowshot of the shore, and, landing, they found, as the journal informs us,

"goodly grapes and rose-trees," which they brought on board with them. He then

weighed anchor and advanced as far as the northern extremity of the headland.

Here he heard the voice of someone calling to them, and, thinking it possible

some unfortunate European might have been left there, he immediately

despatched some of the men to the shore. They found only a few savages; but,

as these appeared very friendly, they brought one of them on board, where they

gave him refreshments and also a present of three or four glass buttons, with

which he seemed greatly delighted. The savages were observed to have green

tobacco and pipes, the bowls of which were made of clay and the stems of red

copper.

The wind not being favorable for passing west of this headland into the

bay, Hudson determined to explore the coast farther south, and the next day he

saw the southern point of Cape Cod, which had been discovered and named by

Bartholomew Gosnold in the year 1602. He passed in sight of Nantucket and

Martha's Vineyard, and continued a southerly course till the middle of August,

when he arrived at the entrance of Chesapeake Bay. "This," says the writer of

the journal, "is the entrance into the King's river, in Virginia, where our

Englishmen are." The colony, under the command of Newport, consisting of one

hundred five persons, among whom were Smith, Gosnold, Wingfield, and

Ratcliffe, had arrived here a little more than two years before, and if Hudson

could have landed he would have enjoyed the satisfaction of seeing and

conversing with his own countrymen, and in his own language, in the midst of

the forests of the New World. But the wind was blowing a gale from the

northeast, and, probably dreading a shore with which he was unacquainted, he

made no attempt to find them.

He continued to ply to the south for several days, till he reached the

latitude of 35 degrees 41 minutes, when he again changed his course to the

north. It is highly probable that if the journal of the voyage had been kept

by Hudson himself we should have been informed of his reasons for changing the

southerly course at this point. The cause, however, is not difficult to

conjecture. He had gone far enough to ascertain that the information given

him by Captain Smith with respect to a passage into the Pacific south of

Virginia was incorrect, and he probably did not think it worth while to spend

more time in so hopeless a search. He therefore retraced his steps, and on

August 28th discovered Delaware Bay, where he examined the currents,

soundings, and the appearance of the shores, without attempting to land. From

this anchorage he coasted northward, the shore appearing low, like sunken

ground, dotted with islands, till September 2d, when he saw the highlands of

Navesink, which, the journalist remarks, "is a very good land to fall with and

a pleasant land to see."

The entrance into the southern waters of New York is thus described in

the journal: "At three of the clock in the afternoon we came to three great

rivers. So we stood along to the northern-most, thinking to have gone into

it, but we found it to have a very shoal bar before it, for we had but ten

foot water. Then we cast about to the southward and found two fathoms, three

fathoms, and three and a quarter, till we came to the southern side of them;

then we had five and six fathoms, and anchored. So we sent in our boat to

sound, and they found no less water than four, five, six, and seven fathoms,

and returned in an hour and a half. So we weighed and went in and rode in

five fathoms, oozy ground, and saw many salmons, and mullets, and rays very

great." The next morning having ascertained by sending in the boat that there

was a very good harbor before him, he ran in and anchored at two cables'

length from the shore. This was within Sandy Hook Bay.

He was very soon visited by the natives, who came on board his vessel,

and seemed to be greatly rejoiced at his arrival among them. They brought

green tobacco, which they desired to exchange for knives and beads, and Hudson

observed that they had copper pipes and ornaments of copper. They also

appeared to have plenty of maize, from which they made good bread. Their dress

was of deerskins, well cured, and hanging loosely about them. There is a

tradition that some of his men, being sent out to fish, landed on Coney

Island. They found the soil sandy, but supporting a vast number of plum-trees

loaded with fruit, and grapevines growing round them.

The next day, the men, being sent in the boat to explore the bay still

farther, landed, probably on the Jersey shore, where they were very kindly

received by the savages, who gave them plenty of tobacco. They found the land

covered with large oaks. Several of the natives also came on board, dressed

in mantles of feathers and fine furs. Among the presents they brought were

dried currants, which were found extremely palatable.

Soon afterward five of the men were sent in the boat to examine the north

side of the bay and sound the river, which was perceived at the distance of

four leagues. They passed through the Narrows, sounding all along, and saw "a

narrow river to the westward, between two islands," supposed to be Staten

Island and Bergen Neck. They described the land as covered with trees, grass,

and flowers, and filled with delightful fragrance. On their return to the ship

they were assaulted by two canoes; one contained twelve and the other fourteen

savages. It was nearly dark, and the rain which was falling had extinguished

their match, so that they could only trust to their oars for escape. One of

the men, John Colman, who had accompanied Hudson on his first voyage, was

killed by an arrow shot into his throat, and two more were wounded. The

darkness probably saved them from the savages, but at the same time it

prevented their finding the vessel, so that they did not return till the next

day, when they appeared, bringing the body of their comrade. Hudson ordered

him to be carried on shore and buried, and named the place, in memory of the

event, Colman's Point.

He now expected an attack from the natives, and accordingly hoisted in

the boat and erected a sort of bulwark along the sides of the vessel, for the

better defence. But these precautions were needless. Several of the natives

came on board, but in a friendly manner, wishing to exchange tobacco and

Indian corn for the trifles which the sailors could spare them. They did not

appear to know anything of the affray which had taken place. But the day

after two large canoes came off to the vessel, the one filled with armed men,

the other under the pretence of trading. Hudson, however, would only allow

two of the savages to come on board, keeping the rest at a distance. The two

who came on board were detained, and Hudson dressed them up in red coats; the

remainder returned to the shore. Presently another canoe, with two men in it,

came to the vessel. Hudson also detained one of these, probably wishing to

keep him as a hostage, but he very soon jumped overboard and swam to the

shore. On the 11th Hudson sailed through the Narrows and anchored in New York

Bay.

He prepared to explore the magnificent river which came rolling its

waters into the sea from unknown regions. Whither he would be conducted in

tracing its course he could form no conjecture. A hope may be supposed to

have entered his mind that the long-desired passage to the Indies was now at

length discovered; that here was to be the end of his toils; that here, in

this mild climate, and amid these pleasant scenes, was to be found that object

which he had sought in vain through the snows and ice of the Arctic zone.

With a glad heart, then, he weighed anchor on September 12th, and commenced

his memorable voyage up that majestic stream which now bears his name.

The wind only allowed him to advance a few miles the first two days of

the voyage, but the time which he was obliged to spend at anchor was fully

occupied in trading with the natives, who came off from the shore in great

numbers, bringing oysters and vegetables. He observed that they had copper

pipes, and earthen vessels to cook their meat in. They seemed very harmless

and well disposed, but the crew were unwilling to trust these appearances, and

would not allow any of them to come on board. The next day, a fine breeze

springing up from the southeast, he was able to make great progress, so that

he anchored at night nearly forty miles from the place of starting in the

morning. He observes that "here the land grew very high and mountainous," so

that he had undoubtedly anchored in the midst of the fine scenery of the

Highlands.

When he awoke in the morning he found heavy mist overhanging the river

and its shores and concealing the summits of the mountains. But it was

dispelled by the sun in a short time, and taking advantage of a fair wind he

weighed anchor and continued the voyage. A little circumstance occurred this

morning which was destined to be afterward painfully remembered. The two

savages, whom he held as hostages, made their escape through the portholes of

the vessel and swam to the shore, and as soon as the ship was under sail they

took pains to express their indignation at the treatment they had received, by

uttering loud and angry cries. Toward night he came to other mountains,

which, he says, "lie from the river's side," and anchored, it is supposed,

near the present site of Catskill Landing. "There," says the journal, "we

found very loving people and very old men, where we were well used. Our boat

went to fish and caught great store of very good fish."

The next morning, September 16th, the men were sent again to catch fish,

but were not so successful as they had been the day before, in consequence of

the savages having been there in their canoes all night. A large number of

the natives came off to the ship, bringing Indian corn, pumpkins, and tobacco.

The day was consumed in trading with the natives and in filling the casks with

fresh water, so that they did not weigh anchor till toward night. After

sailing about five miles, finding the water shoal, they came to anchor,

probably near the spot where the city of Hudson now stands. The weather was

hot, and Hudson determined to set his men at work in the cool of the morning.

He accordingly, on the 17th, weighed anchor at dawn and ran up the river about

fifteen miles, when, finding shoals and small islands, he thought it best to

anchor again. Toward night the vessel, having drifted near the shore,

grounded in shoal water, but was easily drawn off by carrying out the small

anchor. She was aground again in a short time in the channel, but, the tide

rising, she floated off.

The two days following he advanced only about five miles, being much

occupied by his intercourse with the natives. Being in the neighborhood of

the present town of Castleton, he went on shore, where he was very kindly

received by an old savage, "the governor of the country," who took him to his

house, and gave him the best cheer he could. At his anchorage also, five

miles above this place, the natives came flocking on board, bringing a great

variety of articles, such as grapes, pumpkins, beaver and otter skins, which

they exchanged for beads, knives, and hatchets or whatever trifles the sailors

could spare them. The next day was occupied in exploring the river, four men

being sent in the boat, under the command of the mate, for that purpose. They

ascended several miles and found the channel narrow and in some places only

two fathoms deep, but after that seven or eight fathoms. In the afternoon

they returned to the ship. Hudson resolved to pursue the examination of the

channel on the following morning, but was interrupted by the number of natives

who came on board. Finding that he was not likely to gain any progress this

day, he sent the carpenter ashore to prepare a new foreyard, and in the mean

time prepared to make an extraordinary experiment on board.

From the whole tenor of the journal it is evident that great distrust was

entertained by Hudson and his men toward the natives. He now determined to

ascertain, by intoxicating some of the chiefs, and thus throwing them off

their guard, whether they were plotting any treachery. He accordingly invited

several of them into the cabin and gave them plenty of brandy to drink. One

of these men had his wife with him, who, the journal informs us, "sate so

modestly as any one of our countrywomen would do in a strange place"; but the

men had less delicacy, and were soon quite merry with the brandy. One of

them, who had been on board from the first arrival of the ship, was completely

intoxicated, and fell sound asleep, to the great astonishment of his

companions, who probably feared that he had been poisoned, for they all took

to their canoes and made for the shore, leaving their unlucky comrade on

board. Their anxiety for his welfare, however, soon induced them to return,

and they brought a quantity of beads, which they gave him, perhaps to enable

him to purchase his freedom from the spell that had been laid upon him.

The poor savage slept quietly all night, and when his friends came to

visit him the next morning they found him quite well. This restored their

confidence, so that they came to the ship again in crowds, in the afternoon,

bringing various presents for Hudson. Their visit, which was one of unusual

ceremony, is thus described in the journal: "So, at three of the clock in the

afternoon, they came aboard and brought tobacco and more beads and gave them

to our master, and made an oration, and showed him all the country round

about. Then they sent one of their company on land, who presently returned

and brought a great platter full of venison, dressed by themselves, and they

caused him to eat with them. Then they made him reverence, and departed, all

save the old man that lay aboard."

At night the mate returned in the boat, having been sent again to explore

the river. He reported that he had ascended eight or nine leagues, and found

but seven feet of water and irregular soundings.

It was evidently useless to attempt to ascend the river any farther with

the ship, and Hudson therefore determined to return. We may well imagine that

he was satisfied already with the result of the voyage, even supposing him to

have been disappointed in not finding here a passage to the Indies. He had

explored a great and navigable river to the distance of nearly a hundred forty

miles; he had found the country along the banks extremely fertile, the climate

delightful, and the scenery displaying every variety of beauty and grandeur;

and he knew that he had opened the way for his patrons to possessions which

might prove of inestimable value.

It is supposed that the highest place which the Half Moon reached in the

river was the neighborhood of the present site of Albany, and that the boats

being sent out to explore ascended as high as Waterford, and probably some

distance beyond. The voyage down the river was not more expeditious than it

had been in ascending; the prevalent winds were southerly, and for several

days the ship could advance but very slowly. The time, however, passed

agreeably in making excursions on the shore, where they found "good ground for

corn and other garden herbs, with a great store of goodly oaks and

walnut-trees, and chestnut-trees, ewe-trees and trees of sweetwood in great

abundance, and great store of slate for houses, and other good stones"; or in

receiving visits from the natives, who came on the ship in numbers. While

Hudson was at anchor near the spot where the city bearing his name now stands,

two canoes came from the place where the scene of the intoxication had

occurred, and in one of them was the old man who had been the sufferer under

the strange experiment. He brought another old man with him, who presented

Hudson with a string of beads, and "showed all the country there about, as

though it were at his command." Hudson entertained them at dinner, with four

of their women, and in the afternoon dismissed them with presents.

He continued the voyage down the river, taking advantage of wind and tide

as he could, and employing the time when at anchor in fishing or in trading

with the natives, who came to the ship nearly every day, till on October 1st

he anchored near Stony Point.

The vessel was no sooner perceived from the shore to be stationary than a

party of the native mountaineers came off in their canoes to visit it, and

were filled with wonder at everything it contained. While the attention of

the crew was taken up with their visitors upon deck, one of the savages

managed to run his canoe under the stern and, climbing up the rudder, found

his way into the cabin by the window, where, having seized a pillow and a few

articles of wearing-apparel, he made off with them in the canoe. The mate

detected him as he fled, fired at and killed him. Upon this, all the other

savages departed with the utmost precipitation, some taking to their canoes

and others plunging into the water. The boat was manned, and sent after the

stolen goods, which were easily recovered; but as the men were returning to

the vessel, one of the savages, who were in the water, seized hold of the keel

of the boat, with the intention, as was supposed, of upsetting it. The cook

took a sword and lopped his hand off, and the poor wretch immediately sank.

They then weighed anchor and advanced about five miles.

The next day Hudson descended about seven leagues and anchored. Here he

was visited in a canoe by one of the two savages who had escaped from the ship

as he was going up. But fearing treachery, he would not allow him or his

companions to come on board. Two canoes filled with armed warriors then came

under the stern and commenced an attack with arrows. The men fired at them

with their muskets and killed three of them. More than a hundred savages now

came down upon the nearest point of land to shoot at the vessel. One of the

cannon was brought to bear upon these warriors, and at the first discharge two

of them were killed and the rest fled to the woods.

The savages were not yet discouraged. They had doubtless been instigated

to make this attack by the two who escaped near West Point, and who had

probably incited their countrymen by the story of their imprisonment, as well

as by representing to them the value of the spoil, if they could capture the

vessel, and the small number of men who guarded it. Nine or ten of the

boldest warriors now threw themselves into a canoe and put off toward the

ship, but a shot from the cannon made a hole in the canoe and killed one of

the men. This was followed by a discharge of musketry, which destroyed three

or four more. This put an end to the battle, and in the evening, having

descended about five miles, Hudson anchored in a part of the river out of the

reach of his enemies, probably near Hoboken.

Hudson had now explored the bay of New York and the noble stream which

pours into it from the north. For his employers he had secured a possession

which would beyond measure reward them for the expense they had incurred in

fitting out the expedition. For himself he had gained a name that was

destined to live in the gratitude of a great nation through unnumbered

generations. Happy in the result of his labors and in the brilliant promise

they afforded, he spread his sails again for the Old World on October 4th, and

in a little more than a month arrived safely at Dartmouth, in England.

The journal kept by Juet ends abruptly at this place. The question

therefore immediately arises whether Hudson pursued his voyage to Holland, or

whether he remained in England and sent the vessel home. Several Dutch

authors assert that Hudson was not allowed, after reaching England, to pursue

his voyage to Amsterdam; and this seems highly probable when we remember the

well-known jealousy with which the maritime enterprises of the Dutch were

regarded by King James.

Whether Hudson went to Holland himself or not, it seems clear from

various circumstances that he secured to the Dutch Company all the benefits of

his discoveries, by sending to them his papers and charts. It is worthy of

note that the earliest histories of this voyage, with the exception of Juet's

journal, were published by Dutch authors. Moreover, Hudson's own journal, or

some portion of it at least, was in Holland, and was used by De Laet

previously to the publication of Juet's journal in Purchas' Pilgrims. But the

most substantial proof that the Dutch enjoyed the benefit of his discoveries

earlier than any other nation, is the fact that the very next year they were

trading in Hudson River, which it is not probable would have happened if they

had not had possession of Hudson's charts and journal.