The Byzantine Empire, Part One

Eastern Europe, And Russia To 1600

Donald MacGillivray Nicol: Koraës Professor Emeritus of Byzantine and Modern Greek History, Language, and Literature, King's College, University of London. Director, Gennadius Library, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1989–92. Author of The Last Centuries of Byzantium and others.

Byzantium: The Shining Fortress

Introduction

When we speak of the fall of the Roman Empire, we should not forget that in fact only the western portion of that empire succumbed to the Germanic invaders. In the east, the eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire stood for a thousand years as a citadel against the threats of expansion by the Muslims.

The Byzantine Empire made great contributions to civilization: Greek language and learning were preserved for posterity; the Roman imperial system was continued and Roman law codified; the Greek Orthodox church converted some Slavic peoples and fostered the development of a splendid new art dedicated to the glorification of the Christian religion. Situated at the crossroads of east and west, Constantinople acted as the disseminator of culture for all peoples who came in contact with the empire. Called with justification "The City," this rich and turbulent metropolis was to the early Middle Ages what Athens and Rome had been to classical times. By the time the empire collapsed in 1453, its religious mission and political concepts had borne fruit among the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe and especially among the Russians. The latter were to lay claim to the Byzantine tradition and to call Moscow the "Third Rome."

Byzantium: The Shining Fortress

At the southern extremity of the Bosphorus stands a promontory that juts out from Europe toward Asia, with the Sea of Marmora to the south and a long harbor known as the Golden Horn to the north. On this peninsula stood the ancient Greek city of Byzantium, which Constantine the Great enlarged considerably and formally christened "New Rome" in A.D. 330 (see chap. 5).

Constantine had chosen the site for his new capital with care. He placed Constantinople (now Istanbul) on the frontier of Europe and Asia, dominating the waterway connecting the Mediterranean and Black seas. Nature protected the site on three sides with cliffs; on the fourth side, emperors fortified the city with an impenetrable three-wall network. During the fourth and fifth centuries Visigoths, Huns, and Ostrogoths unsuccessfully threatened the city. In the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries, first Persians, then Arab forces, and finally the Bulgarians besieged - but failed to take - Constantinople. Until 1453, with the exception of the Fourth Crusade's treachery, the city withstood all attacks.

The security and wealth provided by its setting helped Byzantium survive for more than a thousand years. Constantinople was a state-controlled, world trade center which enjoyed the continuous use of a money economy - in contrast to the localized systems found in the west. The city's wealth and taxes paid for a strong military force and financed an effective government. Excellent sewage and water systems supported an extremely high standard of living. Food was abundant, with grain from Egypt and Anatolia and fish from the Aegean. Constantinople could support a population of a million, at a time when it was difficult to find a city in Europe that could sustain more than 50,000.

Unlike Rome, Constantinople had several industries producing luxury goods, military supplies, hardware, and textiles. After silkworms were smuggled out of China about A.D. 550, silk production flourished and became a profitable state monopoly. The state paid close attention to business, controlling the economy: A system of guilds to which all tradesmen and members of the professions belonged set wages, profits, work hours, and prices and organized bankers and doctors into compulsory corporations.

Security and wealth encouraged an active political, cultural, and intellectual life. The widespread literacy and education among men and women of various segments of society would not be matched in Europe until, perhaps, eighteenth-century France. Until its fall in 1453, the Byzantine Empire remained a shining fortress, attracting both invaders and merchants.

The Latin Phase

Constantine and his successors struggled to renew the empire. Rome collapsed under the pressure of the Germanic invaders in 476 (see ch. 5). Thanks to its greater military and economic strength, Constantinople survived for a thousand years, despite revolutions, wars, and religious controversy.

Justinian (527-565) was the last emperor to attempt seriously to return the Roman Empire to its first-century grandeur. Aided by his forceful wife Theodora and a corps of competent assistants, he made lasting contributions to Western civilization and gained short-term successes in his foreign policy.

The damage caused by devastating earthquakes (a perennial problem in the area) in the 520s and 530s gave Justinian the opportunity he needed to carry out a massive project of empire-wide urban renewal. He strengthened the walls defending Constantinople and built the Church of the Holy Wisdom, which still stands in the city. The dome of the church is an architectural triumph with forty windows circling its base, producing a quality of light that creates the illusion that the ceiling is floating.

Justinian also reformed the government and ordered a review of Roman law. This undertaking led to the publication of the Code of Justinian, a digest of Roman and church law, texts, and other instructional materials that became the foundation of modern Western law. Justinian also participated actively in the religious arguments of his day.

The emperor's expensive and ambitious projects triggered outbreaks of violence among the political gangs of Constantinople, the circus crowds of the Greens and Blues. ^1 Since ancient times city dwellers throughout the Mediterranean formed groups, each pursuing a set of economic, social, and religious goals. Much like contemporary urban gangs, members of the circus factions moved about in groups and congregated at public events.

[Footnote 1: Alan Cameron, Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), pp. 310-311.]

In Constantinople the Circus took place in the Hippodrome, a structure that could hold 80,000 spectators. There contests of various types were held, including chariot races. The Blues and Greens backed opposing drivers and usually neutralized each other's efforts. In 532, however, the Blues and Greens united to try to force Justinian from the throne. The so-called Nike rebellion, named after the victory cry of the rioters, nearly succeeded. In his Secret Histories, Procopius relates that Justinian was on the verge of running away, until Theodora stopped him and told the frightened emperor:

I do not choose to flee. Those who have worn the crown should

never survive its loss. Never shall I see the day when I am not

saluted as empress. If you mean to flee, Caesar, well and good.

You have the money, the ships are ready, the sea is open. As for

me, I shall stay. ^2

[Footnote 2: Procopius of Caesarea, History of the Wars, I, XXIV, 36-38, trans. S. R. Rosenbaum in Charles Diehl, Theodora: Empress of Byzantium (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1972), pp. 87-88.]

Assisted by his generals, the emperor remained and put down the rebellion.

Justinian momentarily achieved his dream of re-establishing the Mediterranean rim of the Roman Empire. To carry out his plan for regaining the lost half of the empire from the Germanic invaders, he first had to buy the neutrality of the Persian kings who threatened not only Constantinople butalso Syria and Asia Minor. After securing his eastern flank through diplomacy and bribery, he took North Africa in 533 and the islands of the western Mediterranean from the Vandals.

The next phase of the conquest was much more exhausting. Like warriors before and after him, Justinian had a difficult time taking the Italian peninsula. After twenty years, he gained his prize from the Ostrogoths, but at the cost of draining his treasury and ruining Rome and Ravenna. Justinian's generals also reclaimed the southern part of Spain from the Visigoths, but no serious attempt was ever made to recover Gaul, Britain, or southern Germany.

By a decade after Justinian's death, most of the reconquest had been lost. The Moors in Africa, Germanic peoples across Europe, and waves of Asiatic nomadic tribes threatened the imperial boundaries. Ancient enemies such as the Persians, who had been bribed into a peaceful relationship, returned to threaten Constantinople when the money ran out. In addition, the full weight of the Slavic migrations came to be felt. Peaceful though they may have been, the primitive Slavs severely strained and sometimes broke the administrative links of the empire. Finally, the empire was split by debates over Christian doctrine. Two of Justinian's successors succumbed to madness under the stress of trying to maintain order in the empire.

[See Justinian Byzantium: The Byzantine Empiere under Justinian.]

Heraclius: The Empire Redefined

Salvation appeared from the west when Heraclius (610-641), the Byzantine governor of North Africa, returned to Constantinople to overthrow the mad emperor Phocas. Conditions were so dismal and the future appeared so perilous when Heraclius arrived in the capital that he considered moving the government from Constantinople to Carthage in North Africa.

The situation did not improve soon. The Persians marched through Syria, took Jerusalem - capturing the "True Cross" - and entered Egypt. When Egypt fell to the Persians, the Byzantine Empire lost a large part of its grain supply. Two Asiatic invaders, the Avars and the Bulgars, pushed against the empire from the north. Pirates controlled the sea lanes and the Slavs cut land communication across the Balkans. At this moment of ultimate peril, the emperor decided to throw out the state structure that had been in place since the time of Diocletian and Constantine.

Heraclius created a new system that strengthened his army, tapped the support of the church and people, and erected a more efficient, streamlined administration. He determined that the foundation for the redefined empire would be Anatolia (present-day Turkey) and that the main supply of soldiers for his army would be the free peasants living there, rather than mercenaries. In place of the sprawling realm passed on by Justinian, Heraclius designed a compact state and an administration conceived to deal simultaneously with the needs of government and the challenges of defense.

Heraclius' system, known as the theme system, had been tested when the emperor had ruled North Africa. Acting on the lessons of the past four centuries, he assumed that defense was a constant need and that free peasant soldiers living in the theme (district) they were defending would be the most effective and efficient force. He installed the system first in Anatolia, and his successors spread it throughout the empire for the next two centuries. Heraclius' scheme provided sound administration and effective defense for half of the cost formerly required. ^3 As long as the theme system with its self-supporting, land-owning, free peasantry endured, Byzantium remained strong. When the theme system and its free peasantry were abandoned in the eleventh century, the empire became weak and vulnerable.

[Footnote 3: George Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State, trans. Joan Hussey (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1957), pp. 86-90.]

Heraclius fought history's first holy war to reclaim Jerusalem from the Persians. By 626 he stood poised to strike the final blow and refused to be distracted by the Avar siege of Constantinople. He defeated the Persians at Nineva, marched on to Ctesiphon, and finally reclaimed the "True Cross" and returned it to Jerusalem in 630.

Heraclius was unable to savor his victory for long, because the Muslim advance posed an even greater threat to Byzantium. The Muslims took Syria and Palestine at the battle of Yarmuk in 636. Persia fell the following year, and Egypt in 640. Constantinople's walls and the redefined Byzantine state withstood the challenge, enduring two sieges in 674-678 and in 717. When Byzantium faced a three-sided invasion from the Arabs, Avars, and Bulgarians in 717, the powerful leader Leo the Isaurian (717-741) came forward to save the empire. The Byzantines triumphed by using new techniques such as Greek fire, a sort of medieval equivalent of napalm. The substance, a powerful chemical mixture whose main ingredient was saltpeter, caught fire on contact with water and stuck to the hulls of the Arabs' wooden ships. Over the next ten years, Leo rebuilt those areas ruined by war and strengthened the theme system. He reformed the law, limiting capital punishment to crimes involving treason. He decreed the use of mutilation for a wide range of common crimes, a harsh but still less extreme punishment than execution.

The Iconoclastic Controversy

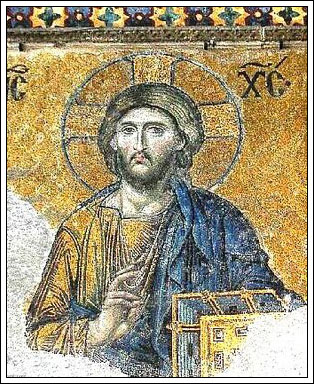

From the beginning, the Byzantine emperors played active roles in the calling of church councils and the formation of Christian doctrine.Leo the Isaurian took seriously his role as religious leader of the empire. He vigorously persecuted heretics and Jews, ordering that the latter must be baptized. In 726 he launched a theological crusade against the use of icons, images or representations of Christ and other religious figures. The emperor was concerned that icons played too prominent a role in Byzantine life and that their common use as godparents, witnesses at weddings, and objects of adoration violated the Old Testament prohibition of the worship of graven images. Accordingly, the emperor ordered the army to destroy icons. This image-breaking, or iconoclastic, policy sparked a violent reaction in the western part of the empire, especially in the monasteries. The government responded by mercilessly persecuting those opposed to the policy. The eastern part of the empire, centered at Anatolia, supported the breaking of the images. By trying to remove what he considered an abuse, Leo split his empire in two.

In Byzantium's single-centered society, this religious conflict had far-reaching cultural, political, and social implications. In 731 Pope Gregory II condemned iconoclasm. Leo's decision to destroy icons stressed the fracturelines that had existed between east and west for the past four centuries, expressed in the linguistic differences between the Latin west and the Greek east. ^4 Leo's successors continued his religious and political policies, and in 754 Pope Stephen II turned to the north and struck an alliance with the Frankish king Pepin. This was the first step in a process that half a century later would lead to the birth of the Holy Roman Empire and the formal political split of Europe into the east and west (see ch. 9).

[Footnote 4: A.N. Stratos, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, I, trans. Marc Ogilvie Grant (Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert, 1968), pp. 37-39.]

There was a brief attempt under the regent, later empress, Irene (797-802), in 787, to restore icons. In 797 she gained power after having her son - the rightful but incompetent heir - blinded in the very room in which she had given him birth. Irene then became the first woman to rule the empire in her own name. She could neither win widespread support for her pro-icon policies, nor could she put together a marriage alliance with the newly proclaimed western emperor Charlemagne, a union which would have brought east and west together. As Irene spent the treasury into bankruptcy, her enemies increased. Finally in 802, they deposed her and exiled her to the island of Lesbos. ^5

[Footnote 5: Romilly Jenkins, Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries, A.D. 610-1071 (New York: Vintage Books, 1969), pp. 90-104.]

The conflict over iconoclasm and Irene's ineptitude placed the empire in jeopardy once again. Her successor, Nicepherous (802-811), after struggling to restore the bases of Byzantine power, was captured in battle with the Bulgarians in 811. The Khan Krum beheaded him and had his skull made into a drinking mug. Soon the iconoclasts made a comeback, but this phase of image-breaking lacked the vigor of the first, and by 842 the policy had been abandoned.

The iconoclastic controversy marked a period when the split between east and west became final. Eastern emperors were strongly impressed by Islamic culture, with its prohibition of images. The emperor Theophilus (829-842), for example, was a student of Muslim art and culture, and Constantinople's painting, architecture, and universities benefited from the vigor of Islamic culture. This focus on the east may have led to the final split with the west, but it also produced an eastern state with its theological house finally in order and its borders fairly secure by the middle of the ninth century.

[See Byzantine Empire 814: The Byzantine Empire about 814]

The Golden Age: 842-1071

For two centuries, roughly coinciding with the reign of the Macedonian dynasty (867-1056), Byzantium enjoyed political and cultural superiority over its western and eastern foes. Western Europe staggered under the blows dealt by the Saracens, Vikings, and Magyars. The Arabs lost the momentum that had carried them forward for two centuries. Constantinople enjoyed the relative calm, wealth, and balance bequeathed by the theme system and promoted by a series of powerful rulers. The time was marked by the flowering of artists, scholars, and theologians as much as it was by the presence of great warriors. It was during this golden age that Constantinople made its major contributions to Eastern Europe and Russia.

Missionaries from Constantinople set out in the 860s to convert the Bulgarian and Slavic peoples and in the process organized their language, laws, esthetics, political patterns, and ethics, as well as their religion. But such transformation did not take place without struggle. Conflict marked the relationship between the Roman and Byzantine churches. The most significant indication of this competition was seen in the contest between the patriarch Photius and Pope Nicholas I in the middle of the ninth century.

Photius excelled both as a scholar and religious leader. He made impressive contributions to universities throughout the Byzantine empire and worked to increase the area of Orthodoxy's influence. Nicholas was his equal in ambition, ego, and intellect. They collided in their attempts to convert the pagan peoples such as the Bulgarians, who were caught between their spheres of influence.

The Bulgarian Khan Boris, as cunning and shrewd as either Photius or Nicholas, saw the trend toward conversion to Christianity that had been developing in Europe since the sixth century and realized the increased power he could gain by the heavenly approval of his rule. He wanted his own patriarch and church and dealt with the side that gave him the better bargain. Between 864 and 866 Boris changed his mind three times over the issue of which holy city to turn to. Finally, the Byzantines gave the Bulgarians the equivalent of an autonomous church, and in return the Bulgarians entered the Byzantine cultural orbit. The resulting schism between the churches set off a sputtering sequence of Christian warfare that went on for centuries. ^6

[Footnote 6: Francis Dvornik, The Photian Schism: History and Legend (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970), passim.]

The work of the Byzantine missionaries Cyril and Methodius was more important than Bulgarian ambitions or churchly competition. The two, who were brothers, were natives of Thessalonica, a city at the mouth of the Vardar-Morava waterway that gave access to the Slavic lands. They learned the Slavic language and led a mission to Moravia, which was ruled by King Rastislav. The king no doubt wanted to convert to Orthodoxy and enter the Byzantine orbit in order to preserve as much independence for his land as he could in the face of pressure from his powerful German neighbors. Cyril and Methodius went north, teaching their faith in the vernacular Slavic language. Cyril devised an alphabet for the Slavs, adapting Greek letters. The two brothers translated the liturgy and many religious books into Slavic. Although Germanic missionaries eventually converted the Moravians by sheer force, the efforts of Cyril and Methodius profoundly affected all the Slavic peoples, whose languages are rooted in the work of the two brothers.

Byzantium continued its military as well as its theological intensity. Arab armies made continual thrusts, including one at Thessalonica in 904 that led to the Byzantine loss of 22,000 people through death or slavery. But during the tenth century the combination of the decline in Muslim combativeness and the solidarity of Byzantine defenses brought an end to that conflict. Basil II (963-1025), surnamed Bulgaroctonus, or Bulgar-slayer, stopped the Bulgarians at the battle of Balathista in 1014. At the same time, the Macedonian emperors dealt from a position of strength with western European powers, especially in Italy, where their interests clashed. Western diplomats visiting the Byzantine court expressed outrage at the benign contempt with which the eastern emperors treated them, but this conduct merely reflected Constantinople's understanding of its role in the world.

By the eleventh century, succession to the Byzantine throne had degenerated into a power struggle between the civil and military aristocracies. On the other hand, the secular and theological universities flourished despite the political instability, and the emperors proved to be generous patrons of the arts. Basil I (867-886) and Leo VI (886-912) oversaw the collection and reform of the law codes. Leo, the most prolific lawgiver since Justinian, sponsored the greatest collection of laws of the medieval Byzantine empire, a work that would affect jurisprudence throughout Europe. Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (912-959) excelled as a military leader, lover of books, promoter of an encyclopedia, and surveyor of the empire's provinces. At a time when scholarship in western Europe was almost nonexistent, Byzantine society featured a rich cultural life and widespread literacy among men and women of different classes.

The greatest contribution to Western civilization made during the golden age was the preservation of ancient learning, especially in the areas of law, Greek science, Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy, and Greek literature. Unlike in the West where the church maintained scholarship, the civil servants of Constantinople perpetuated the Greek tradition in philosophy, literature, and science. Byzantine monasteries produced many saints and mystics but showed little interest in learning and teaching.

Decline And Crusades

Empires more often succumb to internal ailments than to external takeovers and this was the case with the Byzantine empire. As long as Constantinople strengthened the foundations laid by Heraclius - the theme system and reliance on the free peasant-soldier - the empire withstood the military attacks of the strongest armies. When the Byzantine leaders abandoned the pillars of their success, the empire began to falter.

Inflation and narrow ambition ate away at the Heraclian structure. Too much money chased too few goods during the golden age. Land came to be the most profitable investment for the rich, and the landowning magnates needed labor. As prices went up, taxes followed. The peasant villages were collectively responsible for paying taxes, and the rising tax burden overwhelmed them. In many parts of the empire, villagers sought relief by placing themselves under the control of large landowners, thus taking themselves out of the tax pool and lowering the number of peasant-soldiers. Both the state treasury and the army suffered. Until the time of Basil II, the Macedonian emperors tried to protect the peasantry through legislation, but the problem was not corrected. Even though the free peasantry never entirely disappeared and each free person was still theoretically a citizen of the empire, economic and social pressures effectively destroyed the theme system. Exacerbating the problem was the growth of the church's holdings and the large percentage of the population entering church service, thus becoming exempt from taxation.

In the fifty years after the death of Basil II in 1025, the illusion that eternal peace had been achieved encouraged the opportunistic civil aristocracy, which controlled the state, to weaken the army and ignore the provinces. When danger next appeared, no strong leader emerged to save Byzantium. Perhaps this was because no enemies appeared dramatically before the walls of Constantinople.

Instead, a new foe arose, moving haphazardly across the empire. Around the sixth century, the first in a series of waves of Turkish bands appeared in southwest Asia. These nomads converted to Islam and fought with, then against, the Persians, Byzantines, and Arabs. When the Seljuk Turk leader Alp Arslan ("Victorious Lion") made a tentative probe into the empire's eastern perimeter near Lake Van in 1071, the multilingual mercenary army from Constantinople fell apart even before fighting began at the battle of Manzikert. With the disintegration of the army, the only limit to the Turks' march for the next decade was the extent of their own ambition and energy.

Byzantium lost the heart of its empire, and with it the reserves of soldiers, leaders, taxes, and food that had enabled it to survive for the past four centuries. From its weakened position, the empire confronted Venice, a powerful commercial and later political rival. By the end of the eleventh century, the Venetians took undisputed trading supremacy in the Adriatic Sea and turned their attention to the eastern Mediterranean. The Byzantines also faced the challenges of the Normans, led by Robert Guiscard, who took the last Byzantine stronghold in Italy.

In 1081 the Comnenian family claimed the Byzantine throne. In an earlier time, with the empire in its strength this politically astute family might have accomplished great things. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, though, the best they could do was play a balance-of-power game between east and west. Fifteen years later, in 1096, the first crusaders appeared (see ch. 10), partially in response to the Council of Clermont, partially in response to the opportunity for gold and glory. Alexium Comnenus (1081-1118) had appealed to Pope Urban II for help against the Turks, but the emperor had not bargained on finding a host of crusaders, including the dreaded Normans, on his doorstep. Alexius sent them quickly across the Dardanelles where they won some battles and permitted the Byzantines to reclaim some of their losses in Asia Minor. ^7

[Footnote 7: For an eastern perspective, see Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes (New York: Schocken Books, 1985).]

Subsequent crusades, however, failed to bring good relations between east and west, whose churches had excommunicated each other in 1054. By the time of the Fourth Crusade, the combination of envy, hatred, and frustration that had been building up for some time led to an atrocity. The Venetians controlled the ships and money for this crusade and persuaded the fighters to attack the Christian city of Zara in Dalmatia - a commercial rival of Venice - and Constantinople before going on to the Holy Land. Venice wanted a trade monopoly in the eastern Mediterranean more than a fight with the Muslims. Constantinople was paralyzed by factional strife, and for the first time, an invading force captured the city and devastated it far more than the Turks would 250 years later. A French noble described the scene:

The fire...continued to rage for a whole week and no one

could put it out....What damage was done, or what riches

and possessions were destroyed in the flames was beyond the

power of man to calculate....The army...gained much booty;

so much, indeed, that no one could estimate its amount or

its value. It included gold and silver, table-services and

precious stones, satin and silk, mantles of squirrel fur,

ermine and miniver, and every choicest thing to be found on

this earth...so much booty had never been gained in any city

since the creation of the world. ^8

[Footnote 8: Geoffrey de Villehardouin, The Conquest of Constantinople in M. R. B. Shaw, Chronicles of the Crusades (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1963), pp. 79, 92. ]

The Venetians made sure they got their share of the spoils, such as the bronze horses now found at St. Mark's Cathedral in Venice, and played a key role in placing a new emperor on the throne. The invaders ruled Constantinople until 1261. The Venetians put a stranglehold on commerce in the region and then turned their hostility toward the Genoese, who threatened their monopoly.

The Paleologus Dynasty (1261-1453), which ruled the empire during its final two centuries, saw the formerly glorious realm become a pawn in a new game. Greeks may have regained control of the church and the state, but there was little strength left to carry on the ancient traditions. The free peasant became ever rarer, as a form of feudalism (see ch. 8) developed in which nobles resisted the authority of the emperor and the imperial bureaucracy. The solidus, the Byzantine coin which had resisted debasement from the fourth through the eleventh century, now fell victim to inflation. The church, once a major support for the state, became embroiled in continual doctrinal disputes. Slavic peoples such as the Serbs, who had posed no danger to the empire in its former strength became threats. After the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century destroyed the exhausted Seljuq Turks, a new, more formidable threat appeared - the Ottoman, or Osmanli, Turks.

Blessed after 1296 with a strong line of male successors and good fortune, the Ottomans rapidly expanded their power through the Balkans. They crossed the Straits into Europe in 1354 and moved up the Vardar-Morava valleys to take Serres (1383), Sofia (1385), Nish (1386), Thessalonica (1387), and finally Kossovo from the South Slavs in 1389. The Turks won their victories by virtue of their overwhelming superiority in both infantry and cavalry. But their administrative effectiveness, which combined strength and flexibility, solidified their rule in areas they conquered. In contrast to the Christians, both Roman and Byzantine, who were intolerant of religious differences, the Turks allowed monotheists, or any of the believers in a "religion of the book" (the Bible, Torah, or Koran), to retain their faith and be ruled by a religious superior through the millet system, a network of religious ghettoes.

In response to the Ottoman advance, the west mounted a poorly conceived and ill-fated crusade against the Turks at Nicopolis on the Danube in 1396 that led to the capture and slaughter of 10,000 knights and their attendants. Only the overwhelming force of Tamerlane (Timur the Lame), a Turko-Mongol ruler who devastated the Ottoman army in 1402, gave Constantinople and Europe some breathing space.

The end came finally in May 1453. The last emperor, Constantine XI, led his forces of 9,000, half of whom were Genoese, to hold off the 160,000 Turks for seven weeks. Finally, the Ottomans, with the help of Hungarian artillerymen, breached the walls of the beleaguered city. After 1123 years, the Christian capital fell. ^9

[Footnote 9: Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965), passim.]