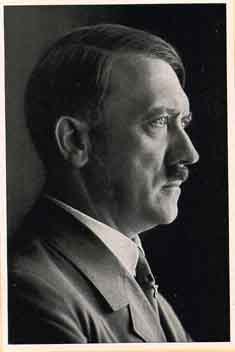

Adolf Hitler, one of history’s most notorious figures, was born on April 20, 1889, in Braunau am Inn, a small town on the Austrian-German border. His life and actions would lead to global devastation and a profound shift in world history. From his humble beginnings, he rose to lead Nazi Germany, leaving a legacy marked by the horrors of the Holocaust, World War II, and the reshaping of 20th-century politics. This article explores the life of Hitler, examining his early years, political ascent, catastrophic rule, and the lasting impact of his actions.

Early Life and Formative Years

Hitler was born into a family with conflicting influences. His father, Alois, was a strict government employee, while his mother, Klara, was a warm and supportive presence in his life. Hitler’s childhood was fraught with tension due to his father’s authoritarian parenting style, and young Adolf often clashed with him. Despite showing some interest in art, his aspirations to become an artist were thwarted when he failed the entrance exam to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts twice, leading to a period of poverty and homelessness in Vienna.

It was during this time in Vienna that Hitler’s worldview began to form. Living in a city where anti-Semitism was prevalent, he was influenced by nationalist and anti-Semitic ideologies that would later define his political platform. Though his personal views at this time remain debated, his exposure to these beliefs laid the groundwork for the prejudices he would later exploit.

World War I: A Turning Point

When World War I broke out in 1914, Hitler enlisted in the German army. He served as a messenger on the Western Front, experiencing the brutal realities of trench warfare. The war was a formative experience for Hitler; he found a sense of purpose in military life and deeply resented Germany’s defeat and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles. The Treaty placed heavy reparations on Germany and limited its military capabilities, which Hitler, along with many Germans, saw as a humiliation. His experiences in the war and resentment of the Treaty’s terms fueled his hatred toward those he believed were responsible for Germany’s loss, particularly the Jewish and socialist communities.

The Birth of the Nazi Party

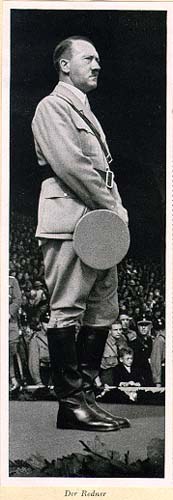

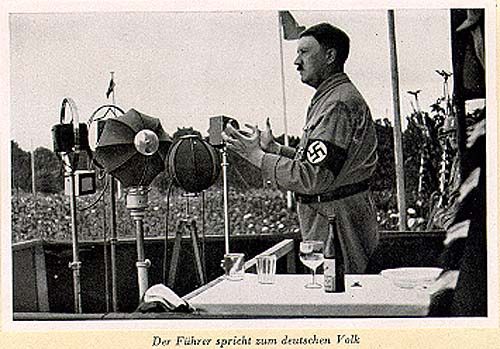

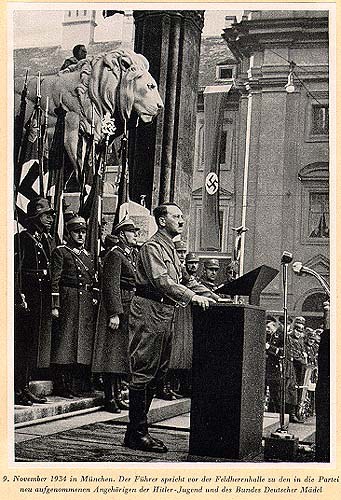

After World War I, Hitler returned to Munich, a city in post-war turmoil. He soon joined the German Workers' Party, which would evolve into the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), or the Nazi Party. In 1920, Hitler became the primary spokesman and leader of the party, known for his powerful oratory skills. His speeches capitalized on the discontent of the German populace, blaming Jews, Marxists, and others he viewed as responsible for Germany's woes.

In 1923, Hitler led the failed Beer Hall Putsch, an attempted coup against the Weimar Republic. Although it resulted in his arrest, this incident brought Hitler and the Nazi Party national attention. While in prison, he wrote Mein Kampf ("My Struggle"), where he outlined his ideology, including ideas of Aryan racial superiority, anti-Semitism, and Lebensraum ("living space"). This book would later serve as the ideological foundation for the Nazi regime.

Rise to Power

Following his release from prison, Hitler focused on legally gaining power. During the 1920s, he restructured the Nazi Party, recruiting a base of supporters that included many who felt abandoned by the economic hardship of the Great Depression. The Nazis promised to restore Germany’s former glory, end unemployment, and reverse the Treaty of Versailles.

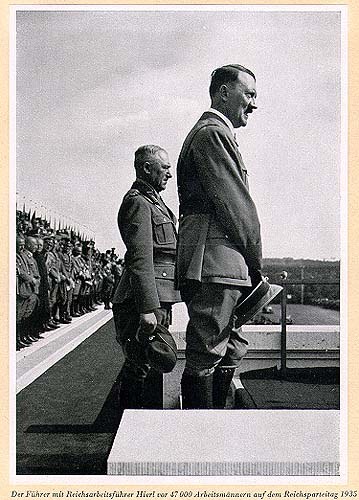

In 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany, a strategic move by conservative politicians who believed they could control him. However, Hitler quickly consolidated power. The Reichstag Fire in February 1933 allowed him to push through the Enabling Act, granting him dictatorial powers. By 1934, with the death of President Paul von Hindenburg, Hitler declared himself Führer (leader), establishing a totalitarian regime.

The Nazi Regime: Repression and Expansion

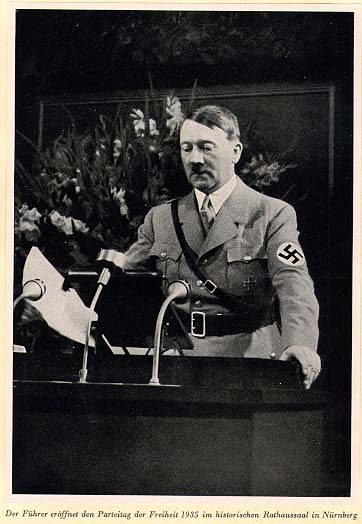

Under Hitler, the Nazi government pursued policies aimed at creating a racially “pure” German state. Anti-Semitic laws, like the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, stripped Jews of citizenship and forbade marriage or sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews. The Nazi regime also targeted political opponents, homosexuals, people with disabilities, and others they deemed "undesirable." The Gestapo, Hitler’s secret police, silenced dissent, and concentration camps were established to imprison those the Nazis considered threats.

With Germany rearmed, Hitler’s ambitions turned outward. He pursued a policy of expansion, annexing Austria in 1938 in the Anschluss and demanding the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia. In 1939, Germany invaded Poland, sparking World War II. Hitler’s strategy relied on blitzkrieg, or "lightning war," which swiftly overwhelmed much of Europe.

The Holocaust: The “Final Solution”

One of the darkest aspects of Hitler’s legacy is the Holocaust. Starting in 1941, the Nazis implemented the "Final Solution," a systematic plan to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population. Six million Jews, along with millions of others, were murdered in concentration camps like Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Sobibor. The genocide represented the brutal culmination of Hitler’s anti-Semitic ideology, carried out with chilling efficiency.

The Holocaust left an indelible scar on history, and its atrocities have since defined global conversations on human rights and genocide. Hitler’s role in this mass extermination remains one of the most studied and condemned aspects of his rule.

World War II: Conquests and Defeat

World War II initially saw major German victories, but Hitler’s ambition eventually led to critical strategic errors. The invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 was perhaps the most significant, as it stretched German resources thin and exposed the army to the harsh Russian winter. The war in the East, particularly the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942-43, marked the beginning of Germany’s decline.

In 1944, Allied forces landed in Normandy, opening a Western Front. By 1945, Germany was surrounded, with Soviet forces advancing from the East and the Allies from the West. As defeat loomed, Hitler retreated to his bunker in Berlin, where he continued to issue orders, detached from the reality of Germany’s dire situation.

Death and Legacy

On April 30, 1945, as Soviet forces closed in on Berlin, Hitler committed suicide in his bunker alongside his wife, Eva Braun, whom he had married shortly before. His death symbolized the collapse of Nazi Germany, which surrendered on May 8, 1945, ending the war in Europe.

Hitler's Enduring Impact

The impact of Hitler’s dictatorship reshaped global history. World War II resulted in an estimated 70-85 million deaths, including those of civilians, soldiers, and victims of the Holocaust. His regime's brutality, propaganda, and militarism led to the establishment of the United Nations and a restructured international order aimed at preventing future atrocities.

In post-war Germany, denazification and the Nuremberg Trials brought Nazi leaders to justice. Hitler’s ideology has been studied as a case of radical authoritarianism, serving as a warning of the dangers of extremism. The world has since grappled with the lessons of the Holocaust, promoting human rights and legislation to combat genocide and racial hatred.

Adolf Hitler remains one of history’s most reviled figures, with his life representing the devastating potential of unchecked power and racial hatred. His policies led to unprecedented suffering, and his influence continues to echo as a reminder of the profound consequences of extremism. The world’s collective response to his legacy has shaped modern political systems, human rights protections, and global unity efforts, underscoring the lessons of tolerance, peace, and vigilance against totalitarianism.