Galileo Overthrows Ancient Philosophy

Author: Lodge, Sir Oliver

Galileo Overthrows Ancient Philosophy

The Telescope And Its Discoveries, A.D. 1610

When the Copernican system of astronomy was published to the world (1543)

it had to encounter, as all capital theories and discoveries in science have

done, the criticism, and, for some time, the opposition, of men holding other

views. After Copernicus, the next great name in modern science is that of

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), who rejected the theory of Copernicus in favor of a

modified form of the Ptolemaic system. This was still taught in the schools

when two mighty contemporaries, geniuses of science, rose to overthrow it

forever.

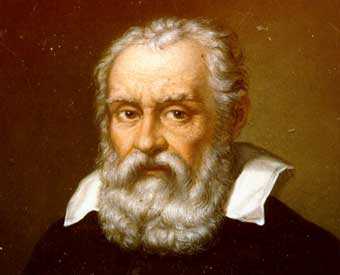

These men were Galileo Galilei - commonly known as Galileo - and Kepler,

both astronomers, though Galileo's scientific work covered also a much wider

field. He is regarded to-day as marking a distinct epoch in the progress of

the world, and the following account of his work by the eminent scientist, Sir

Oliver Lodge, expresses no more than a just appreciation of his great services

to mankind.

Galileo exercised a vast influence on the development of human thought. A

man of great and wide culture, a so-called universal genius, it is as an

experimental philosopher that he takes the first rank. In this capacity he

must be placed alongside of Archimedes, and it is pretty certain that between

the two there was no man of magnitude equal to either in experimental

philosophy. It is perhaps too bold a speculation, but I venture to doubt

whether in succeeding generations we find his equal in the domain of purely

experimental science until we come to Faraday. Faraday was no doubt his

superior, but I know of no other of whom the like can unhesitatingly be said.

In mathematical and deductive science, of course, it is quite otherwise.

Kepler, for instance, and many men before and since, have far excelled Galileo

in mathematical skill and power, though at the same time his achievements in

this department are by no means to be despised.

Born at Pisa on the very day that Michelangelo lay dying in Rome, he

inherited from his father a noble name, cultivated tastes, a keen love of

truth, and an impoverished patrimony. Vincenzo de Galilei, a descendant of

the important Bonajuti family, was himself a mathematician and a musician, and

in a book of his still extant he declares himself in favor of free and open

inquiry into scientific matters, unrestrained by the weight of authority and

tradition. In all probability the son imbibed these precepts: certainly he

acted on them.

Vincenzo, having himself experienced the unremunerative character of

scientific work, had a horror of his son's taking to it, especially as in his

boyhood he was always constructing ingenious mechanical toys and exhibiting

other marks of precocity. So the son was destined for business - to be, in

fact, a cloth-dealer. But he was to receive a good education first, and was

sent to an excellent convent school.

Here he made rapid progress, and soon excelled in all branches of

classics and literature. He delighted in poetry, and in later years wrote

several essays on Dante, Tasso, and Ariosto, besides composing some tolerable

poems himself. He played skillfully on several musical instruments,

especially on the lute, of which indeed he became a master, and on which he

solaced himself when quite an old man. Besides this, he seems to have had

some skill as an artist, which was useful afterward in illustrating his

discoveries, and to have had a fine sensibility as an art critic, for we find

several eminent painters of that day acknowledging the value of the opinion of

the young Galileo.

Perceiving all this display of ability, the father wisely came to the

conclusion that the selling of woollen stuffs would hardly satisfy his

aspirations for long, and that it was worth a sacrifice to send him to the

university. So to the university of his native town he went, with the avowed

object of studying medicine, that career seeming the most likely to be

profitable. Old Vincenzo's horror of mathematics or science as a means of

obtaining a livelihood is justified by the fact that while the university

professor of medicine received two thousand scudi a year, the professor of

mathematics had only sixty; that is thirteen pounds a year, or seven and a

half pence a day. So the son had been kept properly ignorant of such

poverty-stricken subjects, and to study medicine he went.

But his natural bent showed itself even here. For praying one day in the

cathedral, like a good Catholic as he was all his life, his attention was

arrested by the great lamp which, after lighting it, the verger had left

swinging to and fro. Galileo proceeded to time its swings by the only watch

he possessed - viz., his own pulse. He noticed that the time of swing

remained, as near as he could tell, the same, notwithstanding the fact that

the swings were getting smaller and smaller.

By subsequent experiment he verified the law, and the isochronism of the

pendulum was discovered. An immensely important practical discovery this, for

upon it all modern clocks are based; and Huyghens soon applied it to the

astronomical clock, which up to that time had been a crude and quite

untrustworthy instrument.

The best clock which Tycho Brahe could get for his observatory was

inferior to one that may now be purchased for a few shillings; and this change

is owing to the discovery of the pendulum by Galileo. Not that he applied it

to clocks; he was not thinking of astronomy, he was thinking of medicine, and

wanted to count people's pulses. The pendulum served; and "pulsilogies," as

they were called, were thus introduced to and used by medical practitioners.

The Tuscan court came to Pisa for the summer months - for it was then a

seaside place - and among the suite was Ostillio Ricci, a distinguished

mathematician and old friend of the Galileo family. The youth visited him,

and one day, it is said, heard a lesson in Euclid being given by Ricci to the

pages while he stood outside the door entranced. Anyhow, he implored Ricci to

help him into some knowledge of mathematics, and the old man willingly

consented. So he mastered Euclid, and passed on to Archimedes, for whom he

acquired a great veneration.

His father soon heard of this obnoxious proclivity, and did what he could

to divert him back to medicine again. But it was no use. Underneath his

Galen and Hippocrates were secreted copies of Euclid and Archimedes, to be

studied at every available opportunity. Old Vincenzo perceived the bent of

genius to be too strong for him, and at last gave way. With prodigious

rapidity the released philosopher now assimilated the elements of mathematics

and physics, and at twenty-six we find him appointed for three years to the

university chair of mathematics, and enjoying the paternally dreaded stipend

of seven and a half pence a day.

Now it was that he pondered over the laws of falling bodies. He

verified, by experiment, the fact that the velocity acquired by falling down

any slope of given height was independent of the angle of slope. Also, that

the height fallen through was proportional to the square of the time.

Another thing he found experimentally was that all bodies, heavy and

light, fell at the same rate, striking the ground at the same time. Now this

was clean contrary to what he had been taught. The physics of those days were

a simple reproduction of statements in old books. Aristotle had asserted

certain things to be true, and these were universally believed. No one

thought of trying the thing to see if it really were so. The idea of making

an experiment would have savored of impiety, because it seemed to tend toward

scepticism, and cast a doubt on a reverend authority.

Young Galileo, with all the energy and imprudence of youth - what a

blessing that youth has a little imprudence and disregard of consequences in

pursuing a high ideal! - as soon as he perceived that his instructors were

wrong on the subject of falling bodies, instantly informed them of the fact.

Whether he expected them to be pleased or not is a question. Anyhow, they

were not pleased, but were much annoyed by his impertinent arrogance.

It is, perhaps, difficult for us now to appreciate precisely their

position. These doctrines of antiquity, which had come down hoary with age,

and the discovery of which had reawakened learning and quickened intellectual

life, were accepted less as a science or a philosophy than as a religion. Had

they regarded Aristotle as a verbally inspired writer, they could not have

received his statements with more unhesitating conviction. In any dispute as

to a question of fact, such as the one before us concerning the laws of

falling bodies, their method was not to make an experiment, but to turn over

the pages of Aristotle; and he who could quote chapter and verse of this great

writer was held to settle the question and raise it above the reach of

controversy.

It is very necessary for us to realize this state of things clearly,

because otherwise the attitude of the learned of those days toward every new

discovery seems stupid and almost insane. They had a crystallized system of

truth, perfect, symmetrical; it wanted no novelty, no additions; every

addition or growth was an imperfection, an excrescence, a deformity. Progress

was unnecessary and undesired. The Church had a rigid system of dogma which

must be accepted in its entirety on pain of being treated as a heretic.

Philosophers had a cast-iron system of truth to match - a system founded upon

Aristotle - and so interwoven with the great theological dogmas that to

question one was almost equivalent to casting doubt upon the other.

In such an atmosphere true science was impossible. The life-blood of

science is growth, expansion, freedom, development. Before it could appear it

must throw off these old shackles of centuries. It must burst its old skin,

and emerge, worn with the struggle, weakly and unprotected, but free and able

to grow and to expand. The conflict was inevitable, and it was severe. Is it

over yet? I fear not quite, though so nearly as to disturb science hardly at

all. Then it was different: it was terrible. Honor to the men who bore the

first shock of the battle!

Now, Aristotle had said that bodies fell at rates depending on their

weight. A five-pound weight would fall five times as quick as a one pound

weight; a fifty-pound weight fifty times as quick, and so on. Why he said so

nobody knows. He cannot have tried. He was not above trying experiments,

like his smaller disciples; but probably it never occurred to him to doubt the

fact. It seems so natural that a heavy body should fall quicker than a light

one; and perhaps he thought of a stone and a feather, and was satisfied.

Galileo, however, asserted that the weight did not matter a bit; that

everything fell at the same rate - even a stone and a feather, but for the

resistance of the air - and would reach the ground in the same time. And he

was not content to be pooh-poohed and snubbed. He knew he was right, and he

was determined to make everyone see the facts as he saw them. So one morning,

before the assembled university, he ascended the famous leaning tower, taking

with him a one-hundred-pound shot and a one-pound shot. He balanced them on

the edge of the tower, and let them drop together. Together they fell, and

together they struck the ground. The simultaneous clang of those two weights

sounded the death-knell of the old system of philosophy, and heralded the

birth of the new.

But was the change sudden? Were his opponents convinced? Not a jot.

Though they had seen with their eyes and heard with their ears, the full light

of heaven shining upon them, they went back muttering and discontented to

their musty old volumes and their garrets, there to invent occult reasons for

denying the validity of the observation, and for referring it to some unknown

disturbing cause.

They saw that if they gave way on this one point they would be letting go

their anchorage, and henceforward would be liable to drift along with the

tide, not knowing whither. They dared not do this. No; they must cling to

the old traditions; they could not cast away their rotting ropes and sail out

on to the free ocean of God's truth in a spirit of fearless faith.

Yet they had received a shock: as by a breath of fresh salt breeze and a

dash of spray in their faces, they had been awakened out of their comfortable

lethargy. They felt the approach of a new era. Yes, it was a shock, and they

hated the young Galileo for giving it them - hated him with the sullen hatred

of men who fight for a lost and dying cause.

We need scarcely blame these men; at least we need not blame them

overmuch. To say that they acted as they did is to say that they were human,

were narrow-minded, and were the apostles of a lost cause. But they could not

know this; they had no experience of the past to guide them; the conditions

under which they found themselves were novel, and had to be met for the first

time. Conduct which was excusable then would be unpardonable now, in the

light of all this experience to guide us. Are there any now who practically

repeat their error, and resist new truth? who cling to any old anchorage of

dogma, and refuse to rise with the tide of advancing knowledge? There may be

some even now.

Well, the unpopularity of Galileo smouldered for a time, until, by

another noble imprudence, he managed to offend a semiroyal personage, Giovanni

de' Medici, by giving his real opinion, when consulted, about a machine which

De' Medici had invented for cleaning out the harbor of Leghorn. He said it was

as useless as it in fact turned out to be. Through the influence of the

mortified inventor he lost favor at court; and his enemies took advantage of

the fact to render his chair untenable. He resigned before his three years

were up, and retired to Florence.

His father at this time died, and the family were left in narrow

circumstances. He had a brother and three sisters to provide for. He was

offered a professorship at Padua for six years by the Senate of Venice, and

willingly accepted it. Now began a very successful career. His introductory

address was marked by brilliant eloquence, and his lectures soon acquired

fame. He wrote for his pupils on the laws of motion, on fortifications, on

sun-dials, on mechanics, and on the celestial globe: some of these papers are

now lost, others have been printed during the present century.

Kepler sent him a copy of his new book, Mysterium Cosmographicum, and

Galileo, in thanking him for it, writes him the following letter:

"I count myself happy, in the search after truth, to have so great an

ally as yourself, and one who is so great a friend of the truth itself. It is

really pitiful that there are so few who seek truth, and who do not pursue a

perverse method of philosophizing. But this is not the place to mourn over

the miseries of our times, but to congratulate you on your splendid

discoveries in confirmation of truth. I shall read your book to the end, sure

of finding much that is excellent in it. I shall do so with the more

pleasure, because I have been for many years an adherent of the Copernican

system, and it explains to me the causes of many of the appearances of nature

which are quite unintelligible on the commonly accepted hypothesis. I have

collected many arguments for the purpose of refuting the latter; but I do not

venture to bring them to the light of publicity, for fear of sharing the fate

of our master, Copernicus, who, although he has earned immortal fame with

some, yet with very many (so great is the number of fools) has become an

object of ridicule and scorn. I should certainly venture to publish my

speculations if there were more people like you. But this not being the case,

I refrain from such an undertaking."

Kepler urged him to publish his arguments in favor of the Copernican

theory, but he hesitated for the present, knowing that his declaration would

be received with ridicule and opposition, and thinking it wiser to get rather

more firmly seated in his chair before encountering the storm of controversy.

The six years passed away, and the Venetian Senate, anxious not to lose so

bright an ornament, renewed his appointment for another six years at a largely

increased salary.

Soon after this appeared a new star - the stella nova of 1604 - not the

one Tycho had seen - that was in 1572 - but the same that Kepler was so much

interested in. Galileo gave a course of three lectures upon it to a great

audience. At the first the theatre was overcrowded, so he had to adjourn to a

hall holding one thousand persons. At the next he had to lecture in the open

air. He took occasion to rebuke his hearers for thronging to hear about an

ephemeral novelty, while for the much more wonderful and important truths

about the permanent stars and facts of nature they had but deaf ears.

But the main point he brought out concerning the new star was that it

upset the received Aristotelian doctrine of the immutability of the heavens.

According to that doctrine the heavens were unchangeable, perfect, subject

neither to growth not to decay. Here was a body, not a meteor but a real

distant star, which had not been visible and which would shortly fade away

again, but which meanwhile was brighter than Jupiter.

The staff of petrified professorial wisdom were annoyed at the appearance

of the star, still more at Galileo's calling public attention to it; and

controversy began at Padua. However, he accepted it, and now boldly threw

down the gauntlet in favor of the Copernican theory, utterly repudiating the

old Ptolemaic system, which up to that time he had taught in the schools

according to established custom.

The earth no longer the only world to which all else in the firmament

were obsequious attendants, but a mere insignificant speck among the host of

heaven! Man no longer the centre and cynosure of creation, but, as it were,

an insect crawling on the surface of this little speck! All this not set down

in crabbed Latin in dry folios for a few learned monks, as in Copernicus'

time, but promulgated and argued in rich Italian, illustrated by analogy, by

experiment, and with cultured wit; taught not to a few scholars here and there

in musty libraries, but proclaimed in the vernacular to the whole populace

with all the energy and enthusiasm of a recent convert and a master of

language! Had a bombshell been exploded among the fossilized professors it

had been less disturbing.

But there was worse in store for them. A Dutch optician, Hans Lippershey

by name, of Middleburg, had in his shop a curious toy, rigged up, it is said,

by an apprentice, and made out of a couple of spectacle lenses, whereby, if

one looked through it, the weather-cock of a neighboring church spire was seen

nearer and upside down. The tale goes that the Marquis Spinola, happening to

call at the shop, was struck with the toy and bought it. He showed it to

Prince Maurice of Nassau, who thought of using it for military reconnoitring.

All this is trivial. What is important is that some faint and inaccurate echo

of this news found its way to Padua and into the ears of Galileo.

The seed fell on good soil. All that night he sat up and pondered. He

knew about lenses and magnifying-glasses. He had read Kepler's theory of the

eye, and had himself lectured on optics. Could he not hit on the device and

make an instrument capable of bringing the heavenly bodies nearer? Who knew

what marvels he might not so perceive! By morning he had some schemes ready

to try, and one of them was successful. Singularly enough it was not the same

plan as the Dutch optician's: it was another mode of achieving the same end.

He took an old small organ-pipe, jammed a suitably chosen spectacle glass into

either end, one convex, the other concave, and, behold! he had the half of a

wretchedly bad opera-glass capable of magnifying three times. It was better

than the Dutchman's, however: it did not invert.

Such a thing as Galileo made may now be bought at a toy-shop for I

suppose half a crown, and yet what a potentiality lay in that "glazed optic

tube," as Milton called it. Away he went with it to Venice and showed it to

the Seigniory, to their great astonishment. "Many noblemen and senators,"

says Galileo, "though of advanced age, mounted to the top of one of the

highest towers to watch the ships, which were visible through my glass two

hours before they were seen entering the harbor, for it makes a thing fifty

miles off as near and clear as if it were only five." Among the people, too,

the instrument excited the greatest astonishment and interest, so that he was

nearly mobbed. The Senate hinted to him that a present of the instrument

would not be unacceptable, so Galileo took the hint and made another for them.

They immediately doubled his salary at Padua, making it one thousand florins,

and confirmed him in the enjoyment of it for life.

He now eagerly began the construction of a larger and better instrument.

Grinding the lenses with his own hands with consummate skill, he succeeded in

making a telescope magnifying thirty times. Thus equipped he was ready to

begin a survey of the heavens. The first object he carefully examined was

naturally the moon. He found there everything at first sight very like the

earth, mountains and valleys, craters and plains, rocks, and apparently seas.

You may imagine the hostility excited among the Aristotelian philosophers,

especially, no doubt, those he had left behind at Pisa, on the ground of his

spoiling the pure, smooth, crystalline, celestial face of the moon as they had

thought it, and making it harsh and rugged, and like so vile and ignoble a

body as the earth.

He went further, however, into heterodoxy than this: he not only made the

moon like the earth, but he made the earth shine like the moon. The

visibility of "the old moon in the new moon's arms" he explained by

earth-shine. Leonardo had given the same explanation a century before. Now,

one of the many stock arguments against Copernican theory of the earth being a

planet like the rest was that the earth was dull and dark and did not shine.

Galileo argued that it shone just as much as the moon does, and in fact rather

more - especially if it be covered with clouds. One reason of the peculiar

brilliancy of Venus is that she is a very cloudy planet. ^1 Seen from the moon

the earth would look exactly as the moon does to us, only a little brighter

and sixteen times as big - four times the diameter.

[Footnote 1: It is of course the "silver lining" of clouds that outside

observers see.]

Wherever, Galileo turned his telescope new stars appeared. The Milky

Way, which had so puzzled the ancients, was found to be composed of stars.

Stars that appeared single to the eye were some of them found to be double;

and at intervals were found hazy nebulous wisps, some of which seemed to be

star clusters, while others seemed only a fleecy cloud.

Now we come to his most brilliant, at least his most sensational,

discovery. Examining Jupiter minutely on January 7, 1610, he noticed three

little stars near it, which he noted down as fixing its then position. On the

following night Jupiter had moved to the other side of the three stars. This

was natural enough, but was it moving the right way? On examination it

appeared not. Was it possible the tables were wrong? The next evening was

cloudy, and he had to curb his feverish impatience. On the 10th there were

only two, and those on the other side. On the 11th two again, but one bigger

than the other. On the 12th the three reappeared, and on the 13th there were

four. No more appeared. Jupiter, then, had moons like the earth - four of

them in fact! - and they revolved round him in periods which were soon

determined.

The news of the discovery soon spread and excited the greatest interest

and astonishment. Many of course refused to believe it. Some there were who,

having been shown them, refused to believe their eyes, and asserted that

although the telescope acted well enough for terrestrial objects, it was

altogether false and illusory when applied to the heavens. Others took the

safer ground of refusing to look through the glass. One of these who would

not look at the satellites happened to die soon afterward. "I hope," says

Galileo, "that he saw them on his way to heaven."

The way in which Kepler received the news is characteristic, though by

adding four to the supposed number of planets it might have seemed to upset

his notions about the five regular solids.

He says: "I was sitting idle at home thinking of you, most excellent

Galileo, and your letters, when the news was brought me of the discovery of

four planets by the help of the double eyeglass. Wachenfels stopped his

carriage at my door to tell me, when such a fit of wonder seized me at a

report which seemed so very absurd, and I was thrown into such agitation at

seeing an old dispute between us decided in this way, that between his joy, my

coloring, and the laughter of us both, confounded as we were by such a

novelty, we were hardly capable, he of speaking, or I of listening.

"On our separating, I immediately fell to thinking how there could be any

addition to the number of planets without overturning my Mysterium

Cosmographicon, published thirteen years ago, according to which Euclid's five

regular solids do not allow more than six planets round the sun. But I am so

far from disbelieving the existence of the four circumjovial planets that I

long for a telescope to anticipate you if possible in discovering two round

Mars - as the proportion seems to me to require - six or eight round Saturn,

and one each round Mercury and Venus."

As an illustration of the opposite school I will take the following

extract from Francesco Sizzi, a Florentine astronomer, who argues against the

discovery thus:

"There are seven windows in the head - two nostrils, two eyes, two ears,

and a mouth; so in the heavens there are two favorable stars, two

unpropitious, two luminaries, and Mercury alone undecided and indifferent.

From which and many other similar phenomena of nature, such as the seven

metals, etc., which it were tedious to enumerate, we gather that the number of

planets is necessarily seven.

"Moreover, the satellites are invisible to the naked eye, and therefore

can have no influence on the earth, and therefore would be useless, and

therefore do not exist.

"Besides, the Jews and other ancient nations as well as modern Europeans

have adopted the division of the week into seven days, and have named them

from the seven planets: now if we increase the number of the planets this

whole system falls to the ground."

To these arguments Galileo replied that whatever their force might be as

a reason for believing beforehand that no more than seven planets would be

discovered, they hardly seemed of sufficient weight to destroy the new ones

when actually seen. Writing to Kepler at this time, Galileo ejaculates:

"Oh, my dear Kepler, how I wish that we could have one hearty laugh

together! Here, at Padua, is the principal professor of philosophy whom I

have repeatedly and urgently requested to look at the moon and planets through

my glass, which he pertinaciously refuses to do. Why are you not here? What

shouts of laughter we should have at this glorious folly! And to hear the

professor of philosophy at Pisa laboring before the Grand Duke with logical

arguments, as if with magical incantations, to charm the new planets out of

the sky."

A young German protege of Kepler, Martin Horkey, was travelling in Italy,

and meeting Galileo at Bologna was favored with a view through his telescope.

But supposing that Kepler must necessarily be jealous of such great

discoveries, and thinking to please him, he writes: "I cannot tell what to

think about these observations. They are stupendous, they are wonderful, but

whether they are true or false I cannot tell." He concludes, "I will never

concede his four new planets to that Italian from Padua, though I die for it."

So he published a pamphlet asserting that reflected rays and optical illusions

were the sole cause of the appearance, and that the only use of the imaginary

planets was to gratify Galileo's thirst for gold and notoriety.

When after this performance he paid a visit to his old instructor Kepler

he got a reception which astonished him. However, he pleaded so hard to be

forgiven that Kepler restored him to partial favor, on this condition, that he

was to look again at the satellites, and this time to see them and own that

they were there.

By degrees the enemies of Galileo were compelled to confess to the truth

of the discovery, and the next step was to outdo him. Scheiner counted five,

Rheiter nine, and others went as high as twelve. Some of these were

imaginary, some were fixed stars, and four satellites only are known to this

day. ^1

[Footnote 1: A fifth satellite of Jupiter has been recently discovered; and

Kepler's guess at two moons for Mars has also been justified.]

Here, close to the summit of his greatness, we must leave him for a time.

A few steps more and he will be on the brow of the hill; a short piece of

table-land, and then the descent begins.

In dealing with these historic events will you allow me to repudiate once

for all the slightest sectarian bias or meaning? I have nothing to do with

Catholic or Protestant as such. I have nothing to do with the Church of Rome

as such. I am dealing with the history of science. But historically at one

period science and the Church came into conflict. It was not specially one

church rather than another - it was the Church in general, the only one that

then existed in those countries. Historically, I say, they came into

conflict, and historically the Church was the conqueror. It got its way; and

science, in the persons of Bruno, Galileo, and several others, was vanquished.

Such being the facts, there is no help but to mention them in dealing with the

history of science. Doubtless now the Church regards it as an unhappy

victory, and gladly would ignore this painful struggle. This, however, is

impossible. With their creed the churchmen of that day could act in no other

way. They were bound to prosecute heresy, and they were bound to conquer in

the struggle or be themselves shattered.

But let me insist on the fact that no one accuses the ecclesiastical

courts of crime or evil motives. They attacked heresy after their manner, as

the civil courts attacked witchcraft after their manner. Both erred

grievously, but both acted with the best intentions.

We must remember, moreover, that his doctrines were scientifically

heterodox, and the university professors of that day were probably quite as

ready so condemn them as the Church was. To realize the position we must

think of some subjects which to-day are scientifically heterodox, and of the

customary attitude adopted toward them by persons of widely differing creeds.

If it be contended now, as it is, that the ecclesiastics treated Galileo

well, I admit it freely: they treated him as well as they possibly could. They

overcame him, and he recanted; but if he had not recanted, if he had persisted

in his heresy, they would - well, they would still have treated his soul well,

but they would have set fire to his body. Their mistake consisted not in

cruelty, but in supposing themselves the arbiters of eternal truth; and by no

amount of slurring and glossing over facts can they evade the responsibility

assumed by them on account of this mistaken attitude.

We left Galileo standing at his telescope and beginning his survey of the

heavens. We followed him indeed through a few of his first great discoveries

- the discovery of the mountains and other variety of surface in the moon, of

the nebulae and a multitude of faint stars, and lastly of the four satellites

of Jupiter.

This latter discovery made an immense sensation, and contributed its

share to his removal from Padua, which quickly followed it. Before the end of

the year 1610 Galileo had made another discovery - this time on Saturn. But to

guard against the host of plagiarists and impostors he published it in the

form of an anagram, which, at the request of the Emperor Rudolph - a request

probably inspired by Kepler - he interpreted; it ran thus: The farthest planet

is triple.

Very soon after he found that Venus was changing from a full-moon to a

half-moon appearance. He announced this also by an anagram, and waited till

it should become a crescent, which it did. This was a dreadful blow to the

anti-Copernicans, for it removed the last lingering difficulty to the

reception of the Copernican doctrine. Copernicus had predicted, indeed, a

hundred years before, that, if ever our powers of sight were sufficiently

enhanced, Venus and Mercury would be seen to have phases like the moon. And

now Galileo with his telescope verifies the prediction to the letter.

Here was a triumph for the grand old monk, and a bitter morsel for his

opponents.

Castelli writes, "This must now convince the most obstinate." But

Galileo, with more experience, replies: "You almost make me laugh by saying

that these clear observations are sufficient to convince the most obstinate;

it seems you have yet to learn that long ago the observations were enough to

convince those who are capable of reasoning and those who wish to learn the

truth; but that to convince the obstinate and those who care for nothing

beyond the vain applause of the senseless vulgar, not even the testimony of

the stars would suffice, were they to descend on earth to speak for

themselves. Let us, then, endeavor to procure some knowledge for ourselves,

and rest contended with this sole satisfaction; but of advancing in popular

opinion, or of gaining the assent of the book-philosophers, let us abandon

both the hope and the desire."

What a year's work it had been! In twelve months observational astronomy

had made such a bound as it has never made before or since ^1. Why did not

others made any of these observations? Because no one could make telescopes

like Galileo. He gathered pupils round him, however, and taught them how to

work the lenses, so that gradually these instruments penetrated Europe, and

astronomers everywhere verified his splendid discoveries.

[Footnote 1: The next year Galileo discovered also the spots upon the sun and

estimated roughly its time of rotation.]