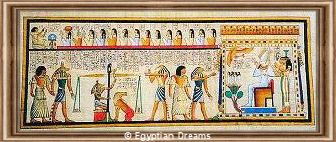

The ancient Egyptians believed that, when they died, they would be judged on their behaviour during their lifetime before they could be granted a place in the Afterlife. This judgement ceremony was called "Weighing of the Heart" and was recorded in Chapter 125 of the funerar text known as the "Book of the Dead".

The ceremony was believed to have taken place before Osiris, the chief god of the dead and Afterlife, and a tribunal of 43 dieties. Standing before the tribunal the deceased was asked to name each of the divine judges and swear that he or she had not committed any offences, ranging from raising the voice to stealing. This was the "negative confession". If found innocent, the deceased was declared "true of voice" and allowed to proceed into the Afterlife.

The proceedings were recorded by Thoth, the scribe of the gods, and the deity of wisdom. Thoth was often dipicted as a human with an ibis head, writing on a scroll of papyrus. His other animal form, the baboon, was often depicted sitting on the pivot of the scales of justice.

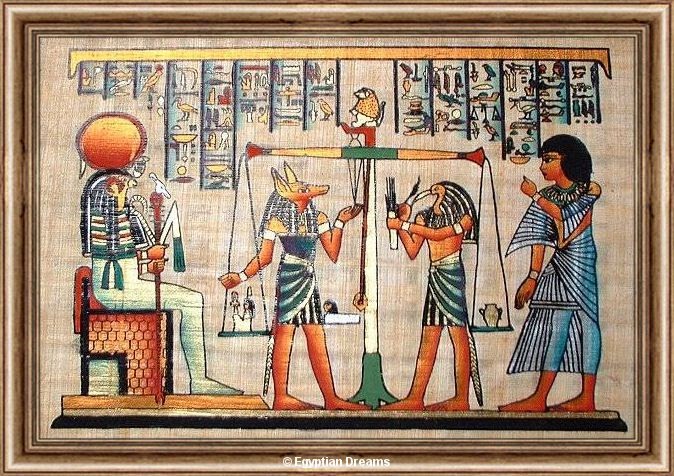

The symbolic ritual that accompanied this ritual was the weighing of the heart of the deceased on a pair of enormous scales. It was weighed against the principle of truth and justice ( known as maat ) represented by a feather, the symbol of the goddess of truth, order and justice, Maat. If the heart balanced against the feather then the deceased would be granted a place in the Fields of Hetep and Iaru. If it was heavy with the weight of wrongdoings, the balance would sink and the heart would be grabbed and devoured by a terrifying beast that sat ready and waiting by the scales. This beast was Ammit, "the gobbler", a composite animal with the head of a crocodile, the front legs and body of lion or leopard, and the back legs of a hippopotamus.

The ancient Egyptians considered the heart to be the centre of thought, memory and emotion. It was thus associated with interlect and personality and was considered the most important organ in the body. It was deemed to be essential for rebirth into the Afterlife. Unlike the other internal organs, it was never removed and embalmed separately, because its presence in the body was crucial.

If the deceased was found to have done wrong and the heart weighed down the scales, he or she was not though to enter a place of tourment like hell, but to cease to exist at all. This idea would have terrified the ancient Egyptians. However, for those who could afford to include Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead in their tombs, it was almost guaranteed that they would pass successfully into the Afterlife. This is because the Egyptians believed in the magical qualities of the actual writings and illustrations in funerary texts. By depicting the heart balancing in the scales against the feather of Maat they ensured that would be the favourable outcome. The entire ceremony was, after all, symbolic.

Following the Weighing of the Heart, the organ was returned to its owner. To make quite sure that this did happen, Chapters 26-29 of the Book of the Dead were spells to ensure that the heart was returned and this it could never be removed again.