Even though much ancient Egyptian written material is still extant, it surely represents only a fraction of what originally existed.

To produce such a mass, there must have been an impressive arsenal of scribes. In fact the word sesh, "scribe," was among the most frequently used titles in ancient Egypt. It is also one of the earliest recorded, and there are representations of scribes carrying the tools of their craft (pigments, water pot, and pen) over their shoulders from various periods beginning with the Old Kingdom.

Eventually scribes made up an entire level of the bureaucracy. They must have had the only profession in the country whose members were aware of almost all that was going on in the empire. Personal letters, diplomatic communications, wills and other legal documents, official proclamations, tax records, administrative, economic, and religious documents, and so forth, all went through their hands. Indeed, even the closing phrase of ancient letters, "May you be well when you hear this," implies that it was in actuality the scribes who not only wrote but also read communications between two people.

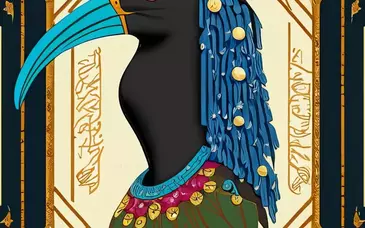

The profession of writing is known among the deities. Thoth, the scribe of the gods, was the patron deity of those in the profession. He is depicted as a baboon, an ibis, or an ibis- headed human. It was he who recorded the verdict at the last judgment of the deceased. His female counterpart was Seshat, and these deities were often shown in their roles as recorders at the coronation of a new pharaoh. The Pharaoh Tutankhamen (Dynasty XVIII, ca. 1336-1327 B.C.) even included writing equipment among the necessities he had with him for the afterlife.

The training of the scribes is well documented and the harsh treatment of apprentices is recorded both in texts and representations. It is perhaps no accident that the ancient Egyptian word for "teach," seba, also means "beat." Today, there are preserved copies of the efforts of some scribal apprentices whose works have been corrected in red by their masters.