Archaeologists in southern Iraq have uncovered a remarkable set of carved clay tablets, offering a rare glimpse into the bureaucratic workings of Akkadia, the world’s first empire. These ancient records, found at the Sumerian city of Girsu (modern-day Tello), shine a light on the sophisticated administrative system of one of the earliest Mesopotamian civilizations.

The tablets were excavated from the ruins of Girsu, which was established around 4500 B.C.E. as part of the Sumerian civilization, the world’s oldest known culture. By the third millennium B.C.E., the Sumerians had built Girsu into a flourishing "megacity" dedicated to the god Ningirsu. This discovery was part of the Girsu Project, a collaborative effort between Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage and the British Museum.

In around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadian king Sargon, who hailed from the ancient city of Akkad, conquered Girsu and other Sumerian cities, bringing them under his centralized rule. This marked the creation of what is now considered the world’s first empire. As Girsu Project Director Sébastien Rey, who also serves as the British Museum’s curator for ancient Mesopotamia, explains, “Sargon developed this new form of governance by conquering all the Sumerian cities of Mesopotamia.”

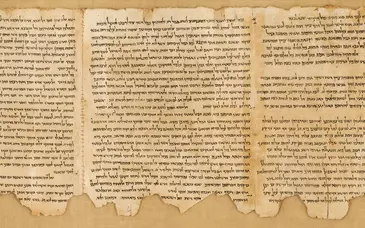

The recent excavation has uncovered more than 200 clay tablets, along with about 50 cylinder seal impressions, depicting Akkadian administrators at work. The tablets provide a fascinating window into the meticulous bureaucracy of the Akkadian Empire.

“These records note absolutely everything,” says Rey. “If a sheep dies at the very edge of the empire, it will be noted. They are obsessed with bureaucracy.”

Written in cuneiform, an ancient script used in the Middle East, the tablets detail a wide range of state affairs. They include blueprints for buildings, maps of irrigation canals, and records of commodities such as livestock, fish, barley, textiles, and even gems. One tablet specifically lists an inventory of goods: “250 grams of gold / 500 grams of silver / … fattened cows … / 30 litres of beer,” according to conservator Dana Goodburn-Brown.

The tablets also reveal the names and roles of people within the society, highlighting a wide array of professions, from stone-cutters to temple-sweepers. Some notable women, such as high priestesses, are also mentioned, though the Akkadian Empire was predominantly governed by men.

Girsu had been known since its rediscovery in the 19th century but had faced significant challenges, including looting and neglect since World War II. The site’s lack of conservation had led to missing or disorganized artifacts, making it difficult to fully understand the scope of the Akkadian government. The newly discovered tablets, however, provide clear evidence of imperial control in the Akkadian Empire and offer unprecedented insights into ancient bureaucracy.

“These new finds were preserved in situ, in their original context, which gives us the first physical evidence of imperial control in the world,” says Rey. “This is completely new.”

This discovery sheds light not only on the administration of the Akkadian Empire but also on the remarkable bureaucratic systems that helped maintain order in one of the earliest known civilizations.