New research is shedding light on the fascinating bouleuterion, the ancient city hall, of Teos, an ancient Greek city located in present-day Turkey.

The ruins of temples, roads, a harbor, and a rainwater cistern near Turkey's western coast reveal the once-thriving metropolis of Teos. Founded around the 10th century B.C.E., Teos grew into a major cultural hub, attracting renowned philosophers and artists. The Greek historian Herodotus even called it "the center of Ionia," referring to the Greek territory in modern-day Turkey.

Now, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania have uncovered new details about Teos’ bouleuterion, its city council building. This site is significant because it offers a glimpse into the civic and cultural life of the city. As Marilyn Perkins reports in Omnia, the University’s arts and sciences alumni magazine, researchers have revealed the building’s construction timeline, deciphered a “monumental” inscription, and uncovered detailed mosaics of animals and dueling cupids. The project, funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation, is a collaboration with the Teos Archaeological Project at Ankara University.

“This is the best-preserved building in the city of Teos, and it seems to preserve for us the early history of Teos underneath it,” says Mantha Zarmakoupi, a classical archaeologist and architectural historian at the University of Pennsylvania.

Zarmakoupi, who has been working in Teos for about four years, became interested in the bouleuterion due to its multiple phases of renovation over the centuries. The ruined structure resembles a Greek theater, with rows of stone bench seating that slope toward a central platform, capable of holding several hundred people.

The bouleuterion was central to civic life in Teos, hosting both government meetings and cultural performances. As Amber Morgan from All That’s Interesting explains, the building served as the "center of democratic decision-making" for the city.

“This building is extremely important for understanding the ancient communities that lived here and their institutions,” notes historian Peter Satterthwaite.

Excavations show that the bouleuterion was originally built around the late third century B.C.E., during the Hellenistic period. Later, during the Roman occupation of Teos, additional structures like a portico and a stage were added, allowing the building to serve theatrical functions.

However, the most significant discoveries made by the team predate the Roman period. The researchers unearthed two well-preserved mosaics from the third century B.C.E. that once adorned the floors of two rooms. One mosaic features a pair of winged cupids, symbols of Eros, the Greek god of love. Eros was often depicted alongside Dionysus, the god of wine, who was also Teos’ patron deity. Teos even boasts a temple dedicated to Dionysus, designed by the famous Hellenistic architect Hermogenes.

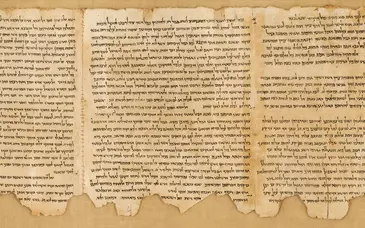

In addition to the mosaics, the team discovered a set of architrave blocks, which were placed above the columns of the building. These blocks were carved with large letters, nearly a foot tall, though someone had attempted to erase the inscription. Using 3D modeling techniques, the researchers were able to reconstruct the blocks and read part of the inscription. It appears to be a dedication to the sponsors who funded the bouleuterion's construction.

“The inscription gives us a really valuable indication of the process by which the structures were built and who was involved,” Satterthwaite explains. “The fact that it’s erased suggests another chapter in the city’s history, when they no longer wished to commemorate certain individuals.”

Though part of the inscription remains missing, Zarmakoupi plans to continue excavations in hopes of completing the text. “Every piece of this process has been revealing itself like an onion,” she says. “It peels off, and another thing arrives.”

This new research provides fresh insights into Teos, offering a clearer picture of its civic structure, artistic achievements, and the cultural exchanges that made it a vital part of ancient Greece.