This page has information on the military of ancient Greece. The tactical warfare page and the armor and weapons page are both about field tactics and armaments; these in turn also show us the mentality and perception of soldiers in ancient Greece. Their armaments as well as their field tactics were fairly crude; however, significant increases in technology, such as shields and javelins, and the growing professionalism in infantry organization thanks to the creation of the phalanx resulted in a revolutionary movement both on and off the field. The military hierarchy parallels their social hierarchy, resulting in an effectivly stratified order of command from which the upper class could retain more power but still relied on the lower classes because of their significance on the battle field, such as the reserves and hoplite soldiers who fulfilled the ranks in the phalanxes. Military pay was fairly nonexistent. Soldiers' pay came from booty from conquests. They could also become mercenaries, though eventually monetary funds were given to regular soldiers. Their military duty ran in accordance to their duty to the state as well as their gods. The act of war was either an act of piety or an act of patriotism to their city state, resulting in warfare that was primarily fought for nonterritoirial gains.

Organized Infantry

Prior to the evolution of the phalanx during the seventh-century BC, war was fought by very limited forces derived exclusively from the social infrastructure of Greek city-states. Quite commonly the aristocratic class constituted the majority of the army. Battles were usually won with specialized offensive charges from which the strongest forces in the army, being that of the chariots and cavalry, often became the decisive factor.

Chariots and horses were obtained solely for the nobility; through their wealth and social supremacy nobles could afford to purchase these military luxuries and would have the leisure time to practice them. Often battles were clashes between the noble classes of differing city-states, henceforth, leading to their hegemony over the rest of the population.

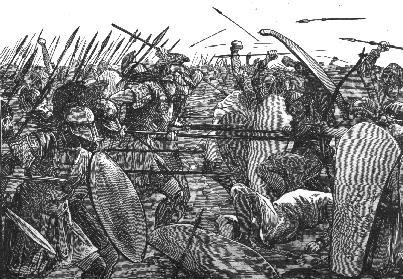

The integration of the phalanx into tactical warfare became a military revolutionary idea as well as a social evolution. The phalanx was composed of a compact unit of men, often longer in length than in depth. The phalanx was not a permanent formation,in that its dimensions and approach to attack varied according to the general's tactics and the size of the army.

The creation of the phalanx made an attack by chariots obsolete. No longer could chariots be considered a significant factor in the tide of battle, which transfered the power of military dominance into the hands of the phalanx's soldiers, known as hoplites. Hoplites were soldiers derived from the yeoman class; this social class was comprised of wealthy men who could not essentially afford a horse but could furnish themselves as heavy-infantry soldiers.

The reallocation of military power into the yeomen class helped to significantly dilute political power among a wider range of the populace leading to a society that still retained its stratified social mentality but helped maintain social order through increased political unity and military prowess.

The new construction of military warfare based on the phalanx helped the Greeks maintain their independence from foreigners who had not yet acquired the phalanx formations.

Behind the phalanx fronts, light-infantry soldiers, who were from a lower social class, came to be a factor in warfare as well. The light-infantry soldier's military role was quite often indirectly linked to victories in battles, in that they were scouts and reserves often lacking sufficient armaments to yield any great threat. During victories over cities or regions the light-infantry were often left to garrison conquered cities or to maintain a rearguard in retreat or frontal movements, leading to their small but somewhat important role in military affairs which ran in accordance to their social subordination at home. The phalanx continued its tactical supremacy for many centuries only to be subdued and rendered obsolete by the professional and perfectionist soldiers in the Roman legions.

Armor and Weapons

The armor and weapons used during war varied in accordance to the wealth of the soldier, technological advancements, and battle tactics. The heavy-infantry soldier was perhaps the most formidable soldier because of his wealth and social stature. The hoplites, who were armed with a variety of armaments, were formed into heavy-infantry phalanxes. These armaments consisted of a javelin varying in length from to the average two and a half meters and a short sword for hand to hand combat, usually ending with one opponent sustaining a prolonged death through a fatal wound (which would often become infected). The defensive armor worn by the hoplites varied over the centuries. The shield evolved from a round mediocre shield about half the size of a man to a large rectangular shield that could better deflect projectile attacks. Later some shields were decreased in size to the point where the shield became a large shoulder plate attached onto the upper arm, which allowed both hands to be free for offensive attacks. The composition of the shield varied from region to region and represented the military identity of the bearer.

A popular folklore phrase of ancient Sparta represents their military heroism on the field, in which the wives of the soldiers would say to their husbands as they left for war "Come back carrying your shields or come back on them." The large rectangular shields of the third century B.C. were commonly used as stretchers for the dead and wounded. Heavy-infantry soldiers wore bronze breastplates that were contoured to their bodies, often in ideal forms to perhaps evoke fear in their enemies. The helmet was decorated according to rank, which also represented social stature, and greaves were also worn. Often the hoplite soldiers who were wealthy enough hired armament bearers, whereas the light-infantry carried their own armaments. Eventually the responsibility of furnishing oneself with weapons and armor was passed to the government, allowing lower class individuals to participate in war. Throughout the centuries armor and weapons became much more technologically efficient and attainable to the greater populace leading to massive offensive fronts which were fought with heavy and light-infantry units along with the support of cavalry. As warfare became much more professional and organized, the need to sufficiently arm and defend the soldiers was prioritized along with military training.

Military Hierarchy

The military hierarchy of ancient Greece could in retrospect be viewed as running parallel to its social hierarchy. The aristocratic class were the wealthiest and most politically powerful individuals of the populace. Their social position gave them an identical stature in the military hierarchy, for they assumed complete authority as trierarchs of both land and sea forces. Not only did they instigate wars but they also led them on the battle fields.

Cavalry members were quite wealthy but were subordinates to the first census class. They supplied chariots and horses and equipped themselves handsomely with armaments; often they were commanders of small units. The hoplite soldiers who formed the phalanx were composed of third class members, and were capable of attaining the necessary skills and equipment to become heavy-infantry soldiers. The lowest class was conscripted into the light-infantry in which they were massed together under the leadership of the generals and commanders. Although the military hierachy was imbued with the same social hierarchy as in their city states the military was much more than an obligatory service. It was a unifying patriotic force that was shared between all social classes on the battle field where each citizen saw himself as a soldier equal to any other.

Military Pay

Pay for military services rendered was essentially nonexistent. Military duty was concieved of as a duty to the state which meant that warfare was part of a citizen's responsibilities. Prior to military salaries, soldiers obtained pay through their victories; they sacked cities and confiscated booty which came to be their reward for military service. Not until the early fifth-century B.C. did payments for military service become common. The Athenians initiated their pay system in a time of peace during the thirty-year truce between the Delian League and the Peloponnesian League .

Although their military payments were smaller than their nonmilitary funds, some soldiers who had no specialized skills in civilian fields found an adventurous and profitable lifestyle through mercenary work. The pay system initiated in Athens gave rise to a new aspect of military duties and the increased growth of professionalism in warfare. Mercenaries also began to play significant roles in battles over both domestic and international disputes, henceforth, leading to a growing theater of war in the Mediterranean states who were no longer bound by their own domestic limits but could now purchase international mercenaries.

Military Duty

Military duty in ancient Greece was perceived and practiced by citizens as an important component of civic duty as well as piety to the gods. The causes of war were usually political , naturally imbued with pious issues, and were also instigated by breaches in good faith between city-states. The citizen of ancient Greece was also a soldier, allowing him to engage in war and to become involved in civic duties. The predominant duty of the citizen was his participation in war, through which he was partaking in the act of defence of the values and honor of his city-state, regardless of whether the war was defensive or offensive.

Military duty also ran in accordance with piety to the gods, which also correllated with civic responsibilities. Piety to the gods appears to been important in warfare, in that the soldier felt it an obligation to uphold his courage and hardships in war as an act of piety; also, in defending a city state, a soldier was also protecting the city's overseer, either a god or goddess.

In essence, military duty was composed of two themes which were integrated into a whole institutional form of duty. Piety was upheld through sacrifices and obedience, which evolved on the battlefield through personal acts of piety by means of virtue and valour. Civic duties were instituted on the battlefield by the citizen's direct involvment in war, henceforth, spreading civil duties into the domain of military duties. The composition of the citizen's military duty was essentially the integration of pious and civil obligations into that duty, from which the city-state and its god both instituted a parallel function into military responsibilities.

Questions

1. What was the most significant creation of warfare in ancient Greece?

2. How did the hoplite soldier affect social evolution in ancient Greece?

3. What did the women of ancient Sparta state to their husbands as they left for war?

4. Were soldiers paid money for their services?

5. Why would soldiers fight without receiving anything in return for their hardships?