| Quick Facts | |

| Type | Logophonetic |

| Genealogy | Cuneiform |

| Location | West Asia > Mesopotamia |

| Time | ~2500 BCE to 100 CE |

| Direction | Variable |

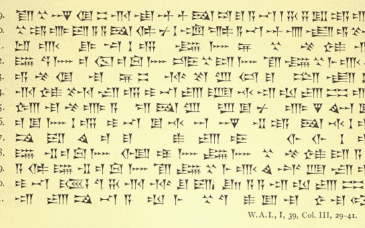

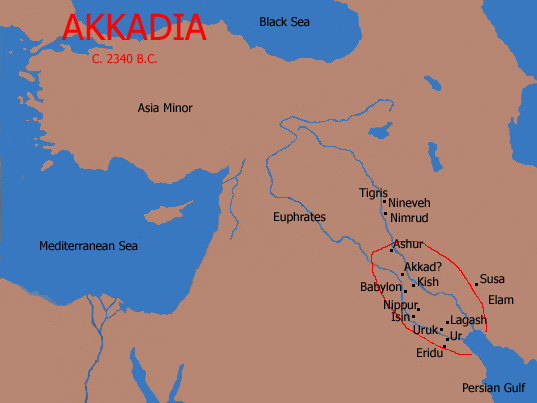

While the cuneiform writing system was created and used at first only by the Sumerians, it did not take long before neighboring groups adopted it for their own use. By about 2500 BCE, the Akkadian, a Semitic-speaking people that dwelled north of the Sumerians, starting using cuneiform to write their own language. However, it was the ascendency of the Akkadian dynasty in 2300 BCE that positioned Akkadian over Sumerian as the primary language of Mesopotamia. While Sumerian did enjoy a quick revival, it eventually became a dead language used only in literary contexts, whereas Akkadian would continue to be spoken for the next two millenium and evolved into later (more famous) forms known as Babylonian and Assyrian.

Syllabic Writing

Sumerian and Akkadian are vastly different languages. Sumerian is a more agglutinative language, where phonetically unchanging words and particles are joined together to form phrases with increasingly complex meaning. Akkadian, however, is infectional, meaning that the basic form of a word, called a root, can be modified in a myriad of ways to create words of related but different meanings. In particular, the basis of Semitic languages is the triconsonantal root, which is a sequence of three consonants representing the most basic and abstract form of a word. Inflections include added vowels between consonants of the root as well as added prefixes and suffixes to the root. For example, in Arabic, the triconsonantal root ktb represent the idea of writing, but by itself it doesn't mean anything. Inflections of this root, however, creates a breadth of words, such as /kitāb/ "book", /kutub/ "books", /kātib/ "writer", /kataba/ "he writes", and so on.

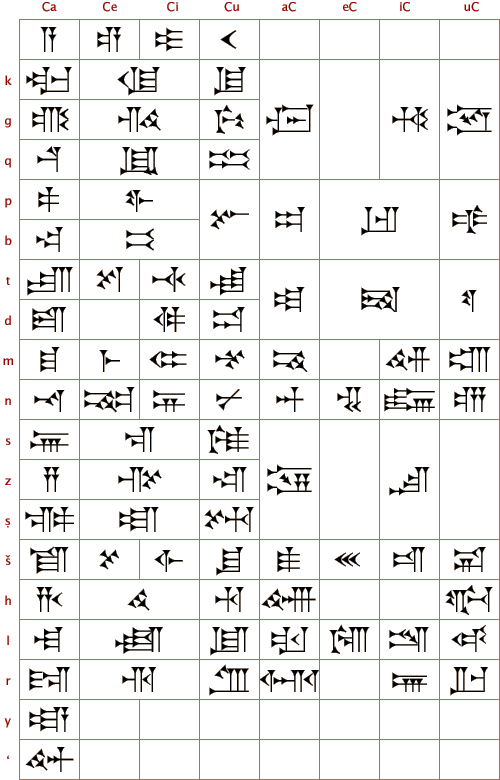

The implication of this is that whereas it was acceptable to simply juxtapose logographic signs in Sumerian to write out a sentence, using the same logograms in Akkadian would not convey the exact meaning of a word. In order to more faithfully reproduce the correct inflection of a word, some signs were used for their phonetic values rather than their meanings. Eventually, Akkadians came to regularly use a group of signs for their phonetic values. We call these signs phonograms. Many of these signs are "simple" These signs became the Akkadian "syllabary", as illustrated below:

Note that the first four columns (with headings "Ca", "Ce", "Ci", and "Cu") represent syllabic signs that start with a consonant on the left side of the chart, the exception being the first row which are pure vowels. The last four columns ("aC", "eC", "iC", and "uC") are signs that end with a consonant.

Also, recall in Sumerian very often different signs represent the same sound, a phenomenon called homophony, due to the fact that words in the Sumerian language tends to be monosyllabic. Since Akkadian adopted the Sumerian writing system, it also inherited all its homophonous sounds. For simplicity sake, I only listed one sign per syllable in the previous chart, but in fact it is possible to have multiple signs for the same syllable. In the traditional transliteration scheme, the first homophone of a sign has an acute accent over the vowel, like á. The second homophone has a grave accent over its vowel, like à. All other homophones have a subscript at the end starting with 4, such as a4, a5, a6, etc.

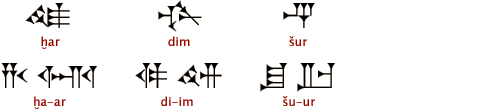

In addition, there are signs that represent a syllable of the structure consonant, vowel, and consonant (CVC). Another way to write these CVC syllables is to write a consonant-initial sign followed by a consonant-final sign, where the vowels of both signs being equal. The following example shows some CVC phonograms on the first row, and the same CVC syllable written as sequences of Cv-VC signs.

However, even though the Akkadian language can be wholly written by phonetic signs, tradition dictated that the full spectrum of signs, namely logograms and determinatives, be used in conjunction.

Logograms and Determinatives

Logograms are signs that represent words or morphemes. Determinatives are unpronounced signs used to denote the general meaning or categorization of following words. However, logograms and determinatives do not form separate groups of signs. In fact, nearly all determinatives are taken from logograms. Moreover, a good amount of phonetic signs also double as logograms and, by extension, determinatives. A sign that has more than one function is polyvalent. Only through the context in which a polyveant sign occurs can one tell if it functions as a phonetic sign, a logogram, or a determinative.

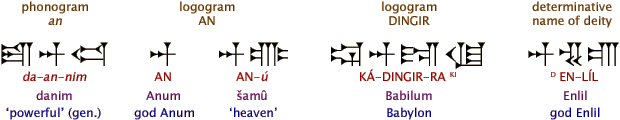

One common sign that can be used as all three types of signs is

, which is a phonetic sign denoting the syllable an. In addition, it also stands for three logograms: the word ilum which means "god" (but transliterated as DINGIR, the Sumerian word for "god"), the god of heaven Anum, and then by extension the word šamû which means "heaven". And on top of all this, it can also function as a determinative for names of deities. The following example illustrates this polyvalency:

Quick note on the traditional transliteration of Akkadian signs: Phonograms are written in italic. Logograms are written in capitals, often transcribing Sumerian words, but also sometimes Akkadian if the logogram has more meanings in Akkadian than in Sumerian. The superscripts are determinatives, and they tend to use the same convention as logograms (capital letters transcribing Sumerian words). The only exception is the determinative for deity names, which is shortened to D instead of DINGIR.

Going back to the example, you have most likely noticed that the same sign can represent different words. This polyvalency originated in Sumerian when the same logogram was used to write related words that had vastly different pronunciations. To distinguish between different readings, contextual information is extremely important. One kind of hint to indicate which word the logogram referes is the phonetic complement. It is a phonogram that spells out part of the word that the logogram represents, and so allow the reader to identify the word. In the example, the sign sequence AN-ú identifies the word šamû, not the deity Anum. Another form of hint is the determinative. The sequence KÁ-DINGIR-RA is followed by the determinative KI, meaning that is must be the name of a city. Only one city is written as KÁ-DINGIR-RA, and that would be Babylon. In fact, the logogram KÁ represents the word babu ("gate"), DINGIR resolves to ilum ("god"), and RA is the genitive case in Sumerian for dingir. Together the sequence gives Babilum, or "Gate of the God", where the god in question would be Marduk, the patron god of Babylon.

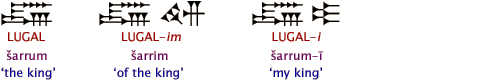

Because of the inflected nature of the Akkadian language, a logogram often only represents the root, or basic form, of a word. To derive other forms of the word, phonetic complements are added to the logogram to indicate inflectional endings.

Note that the logogram for "king", šarrum in Akkadian, is transliterated as LUGAL, which is Sumerian for "king".

As you have no doubtly gathered by now, the Akkadian script was an extremely complex writing system. The number of signs used hover from 200 to 400 (although the total number of signs is between 700 and 800), and homophony and polyvalency give Akkadian scribes multiple ways to spell the same sequence of sounds. However, it remained as one of the great writing systems of the ancient Middle East, preserving the history, literature, and science of the ancient Mesopotamians for the modern world.

Related links: