Roman Law One of the greatest legacies of Rome is their legal system. The development of Roman law began with the Twelve Tables in the mid-fifth century B.C. During a period of over 1000 years, the Roman jurists created a rich literature about all aspects of law: property, marriage, guardianship and family, contracts, theft, and inheritance. Roman law laid the foundations for much of Western civil and criminal law.

The Roman Family The family came first for the Romans, before all other obligations; such as, civil, politic, and military obligations. The family was the vehicle for transmission of moral character. The institution of the Roman family was strengthened by a healthiness, a solidarity, and a spirit of uprightness and self-restraint superior to that of perhaps all other ancient peoples. Roman families were very diverse. The Basis of Roman civil law was the familia, a group consisting of a head, the paterfamilias, and his descendants in the male line. Free members and slaves, all under the guardianship and control of the paterfamilias, were also part of the familia. Free members were the wives, unmarried children (biological and adopted) and other dependents. The members of the familia had no voice in the Curiae, yet they were subject to its decisions and laws, as well as to the decisions made on the family level by the patriarch.

Bust of a Roman Couple

Marriage Marriage is the association of a man and woman, the sharing of every aspect of life and a point where human and divine laws meet. A Roman husband and wife came together in order to lead their lives in common and to produce children. Marriage often coincided with the beginning of adulthood for girls and symbolized with this transition. Marriages were arranged between the bride's father and her husband to be. The father also had the power to end the marriage in divorce. There were three types of marriage in ancient Rome; by usus (cohabitation), by confarreatio (religious ceremony), and by coemptio (purchase). Marriage by usus always required the woman to be married with manus. In a marriage involving manus, the father of the bride relinquishes his control over his daughter to the new husband. Usus also required that the woman had to remain and stay in her husband's house for one year, cohabitating with him, assuming the position of daughter in the family. Marriage by confarreatio involved a religious ceremony. This type of marriage was usually reserved for the wealthy. Religious wedding ceremonies were expensive and included difficult rituals. A woman in this situation was married with manus. After Augustus, marriage with manus was a formal requirement only, but was still required forthe ceremony. A woman married with coemptio was symbolically "purchased" by her new husband from her father. She did not become a slave to her new husband, but he had total control over her. She was his property. All women had to have a guardian who handled their finances and legal affairs. It was the Roman ideal that affection between the husband and wife should develop after marriage. Conjugal love was something that should be calm and nondisturbing, something to be cultivated.

Relief Depicting Roman Marriage Ceremony

Purposes and Benefits of Marriage The purpose of marriage was to carry on the family line by having children, and so the spirits of the dead could be honored. Marriage, for both males and females, granted them a larger network of family members and the security that came with it. Through marriage, the woman could also gain her husband's social status. Roman marriage was monogamous, there was only one woman in the household; her role was wife to the paterfamilias and mother to his children. Caesar Augustus encouraged marriage and having children. He assessed heavier taxes on unmarried men and women and, by contrast, offered rewards for marriage and child bearing. Since there were more males than females among the nobility, he permitted that anyone who wished (except for senators) to marry freedwomen could do so, and decreed the children of these marriages to be legitimate, (Suetonius). Some citizens of Rome resented this moral legislation, but it was for the purity of the upperclass descent. Augustus wrote in 17 B.C. "If we could survive without a wife, citizens of Rome, all of us would do without that nuisance; but since nature has so decreed that we cannot live comfortably with them, nor live in any way without them, we must plan for our lasting preservation rather than for our contemporary pleasure." For the Roman, a successful marriage was one that produced children. Marriage was a practice dictated by necessity.

Bust of Caesar Augustus

Expectations of Women in a Marriage Once married, a woman was under the complete jurisdiction of the paterfamilias. A wife was expected to be modest, chaste, obedient, hard working, industrious, and virtuous. She was expected to produce and raise children. Her household chores included spinning, weaving, cooking, ordering the slaves, and teaching the children during their first few years. When men were away at war, it was not uncommon for the woman to take over the family business. Although wives had lots of responsibilities, they were also free to see friends, shop, attend plays and public shows, relax at the baths, and take part in religious activities.

A Mother Reads to Her Child

Paterfamilia's Rights Over the Family The formal head of the legally recognized family, the paterfamilias, was the oldest surviving male ascendant, and his authority over his descendants lasted until his death, unless formally resolved by a legal act. He was the anchor of the family, the decision maker, and the financial manager. Women, children, and slaves had a very inferior status. They had a constant awareness of his power and position. Every member of the familia was in the potestas of the paterfamilias. The virtually absolute power of the paterfamilias over the rest of his household may have been necessary or desirable in early days when the state had no regular courts or police force and did not involve itself in private morality. The father of the Roman family had the power over everyone and everything in the home. This power was legally recognized. If any member of the family behaved in any way that he considered exceeding the boundaries of proper behavior he had the power to punish the offender with harsh sentences, such as, banishment, slavery, and death. This power extended to the man's slaves and tenant farmers as well. Only the paterfamilias had the right before law to buy, sell, or hold property. He owned, as agent and trustee, all the property of the extended family and held absolute power over persons within his household. As long as the paterfamilias was alive, the sons could not own property or have legal authority over their own children. Though the paterfamilias had the authority to do all of these things, if he inflicted terrible punishment or wasted family property, his reputation would be ruined. Sometimes a father would let his son go on to rule his own family. Upon the paterfamilia's death, each of the sons became rulers of their own households.

Potestas Potestas was a Roman concept central in expressing relationships within the household. Potestas was endowed upon the paterfamilias. By giving the paterfamilias virtually absolute authority and unfettered power over all the members of the household up until the time of his death, potestas excluded any possibility that the paterfamilia's capacity to manage might be challenged. Potestas in this sense is not a constitutional power, but neither is it extra-legal; it refers to social, not political relationships. The potestas of a paterfamilias over his family was unquestionable.

Pregnancy, Status, and Paternity By having children a woman could increase her status in society. There was a public as well as a private importance attached to childbirth. In Paul's Opinions, he sets up principles of laws regarding pregnancy, status, and paternity.

- (1) If a female slave conceives, and has a child after she has been manumitted, the child will be free. (2) If a freedwoman conceives and has a child after having becoming a slave, the child will be free; for this is demanded by the favour conceded to freedom. (3) If a female conceives, and in the meantime is manumitted, but, having subsequently again become a slave, has a child, it will be free; for the intermediate time can benefit but not injure freedom. (4) A child born to a woman who should have been manumitted under the terms of a trust is born free, if it comes into the world after the grant of freedom is in default. (5) If, after a divorce, a woman finds herself to be pregnant, she should within thirty days notify either her husband or his father to send witness for the purpose of making an examination of her condition: and if this is done, they shall in any event be compelled to recognize the child of the woman. (6) If the woman does not announce that she is pregnant, or does not admit witness sent to make an examination of her, neither the father nor the grandfather will be compelled to support the child, but the neglect of the mother will not offer any impediment to the child's being considered the proper heir of his father. (7) Where a woman denies that she is pregnant by her husband, the latter is permitted to make an examination of her, and to appoint persons to watch her. (8) The physical examination of the woman is made by five midwives, and the decision of the majority shall be held true. (9) It has been decided that a midwife who introduces the child of another in order that it may be substituted shall be punished with death.

Bust of a Typical Roman Mother

Children Sons were preferred over daughters. One old law states that fathers had to raise all of their sons but only their first daughter. Girls did not have their own names, instead, they had the feminine form of their father's first name followed by the rest of the father's name in the genitive case showing possession. Right after a child was born it was laid at its father's feet and if the father took it into his arms, it was his and became part of the family. Otherwise the child would be disowned and left on the street to die or to be taken by slave traders. In a regular Roman marriage, children took their status from that of their father at the time of their conception, otherwise they took the status from that of their mother at the time of their birth.

Bust of a Young Girl

Roman Boy Wearing a Toga

Laws on Adultery Despite the fact that law frowned upon adultery, many men and women resorted to adultery out of dissatisfaction from their own marriages. In 18 B.C., Caesar Augustus turned his attention to social problems in Rome. Extravagance and adultery were widespread. Augustus, hoping to elevate the morals, increase the numbers of the upper classes in Rome and the population of native Italians in Italy enacted new laws. Those laws encouraged marriage, procreation, and established adultery as a crime. The laws against adultery made the offense a crime punishable by exile and confiscation of property. Fathers were permitted to kill daughters and their partners in adultery. Husbands could kill the partners under certain circumstances and were required to divorce adulterous wives.

The Consequences of Adultery Paul wrote of the consequences of adultery in his Opinions. Macer and Ulpian also wrote laws concerning the consequences of adultery.

- (1) In the second chapter of the lex Julia concerning adultery, either an adoptive or a natural father is permitted to kill with his own hands an adulterer caught in the act with his daughter in his own house or in that of his son-in-law, no matter what his rank may be. (2) If a son under paternal power, who is the father, should surprise his daughter in the act of adultery, while it is inferred from the words of the law that he cannot kill her, still, he ought to be permitted to do so. (3) Again, it is provided in the fifth chapter of the lex Julia that it is permitted to detain an adulterer who has been caught in the act for twenty hours, calling neighbours to witness. (4) A husband cannot kill anyone taken in adultery except persons who are infamous, and those who sell their bodies for gain, as well as slaves. His wife, however, is excepted, and he is forbidden to kill her. (5) It has been decided that a husband who kills his wife when caught with an adulterer should be punished more leniently, for the reason that he committed the act through impatience caused by just suffering. (6) After having killed the adulterer, the husband should at once dismiss his wife, and publicly declare within the next three days with what adulterer, and in what place he found his wife. (7) A husband who surprises his wife in adultery can only kill the adulterer when he catches him in his own house. (8) It has been decided that a husband who does not at once dismiss his wife whom he has taken in adultery can be prosecuted as a pimp. (10) It should be noted that two adulterers can be accused at the same time with the wife, but more than that number cannot be. (11) It has been decided that adultery cannot be committed with women who have charge of any business or shop. (12) Anyone who has sexual relations with a free male without his consent shall be punished with death. (13) It has been held that women convicted of adultery shall be punished with the loss of half of their dowry and the third of their goods, and by relegation to an island. The adulterer, however, shall be deprived of half his property, and shall also be punished by relegation to an island; provided the parties are exiled to different islands. (14) It has been decided that the penalty for incest, which in case of a man is deportation to an island, shall not be inflicted upon the woman; that is to say when she has not been convicted under the lex Julia concerning adultery. (15) Sexual intercourse with female slaves, unless they are deteriorated in value or an attempt is made against their mistress through them, is not considered an injury. (16) In a case of adultery a postponement cannot be granted. Papinian, Ulpian, and Macer also wrote on adultery. (Papinian) The right is granted to the father to kill an adulterer with a daughter while she is under his power. Therefore no other relative can legally do this, nor can a son in paternal power, who is a father. (Ulpian) Hence it can happen that neither the father nor the grandfather can kill the adulterer. This is not unreasonable, for he cannot be considered to have anyone in his power who is not subject to his power. (Papinian) In this law, the natural father is not distinguished from the adoptive father. (1) In the accusation of his daughter, who is a widow, the father is not entitled to the preference. (2) The right to kill the adulterer is granted to the father in his own house, even though his daughter does not live there, or in the house of his son-in-law ... (4) Hence the father, and not the husband, has the right to kill the woman and any adulterer; for the reason that, in general, paternal affection is solicitous for the interests of the children, but the heat and impetuosity of the husband, who decides too quickly, had to be restrained. (Ulpian) What the law says, that is, 'if he finds the adulterer in his daughter,' does not seem to be superfluous; for it signifies that the father shall have this power only if he surprises his daughter in the very act of adultery. Labeo also adopts this opinion; and Pomponius says that the man is killed when caught in the very performance of the sexual act. This is what Solon and Dracho mean by "in the act" (en ergôi). (1) It is sufficient for the father for his daughter to be subject to his power at the time when he kills her, although she may not have been at the time when he gave her in marriage; for suppose that she had afterwards come under his power. (2) Therefore the father shall not be permitted to kill the parties wherever he surprises them, but only in his own house, or in that of his son-in-law. The reason for this is, that the legislator thought that the injury was greater where the daughter caused the adulterer to be introduced into the house of her father or her husband. (3) If, however, her father lives elsewhere, and has another house in which he does not reside, and his daughter is caught there, he cannot kill her. (4) Where the law says, 'He may kill his daughter at once,' this must be understood to mean that having today killed the adulterer he cannot reserve his daughter to be killed some days later; and vice versa; for he should kill both of them with one blow and one attack, being inflamed by the same resentment against both. But if, without any connivance on his part, his daughter should take to flight, while he is killing the adulterer, and she should be caught and put to death some hours afterwards by her father, who pursued her, he will be considered to have killed her immediately. (Macer) A husband is also permitted to kill a man who commits adultery with his wife, but not everyone without distinction, as the father is; for it is provided by this law that the husband can kill the adulterer if he surprises him in his own house (but not in the house of his father-in-law), nor if the adulterer was formerly a pimp; or formerly exercised the profession of an actor or appeared on the stage to dance or sing; or had been convicted in a criminal prosecution and not been restored to his civil rights; or if he is the freedman of the husband or the wife, or of the father or mother, or of the son or the daughter of either of them (nor does it make any difference whether he belonged exclusively to one of the persons above mentioned, or was held in common with another), or if he is a slave. (1) It is also provided that a husband who has killed any one of these must dismiss his wife without delay. (2) It is held by many authorities to make no difference whether the husband is his own master, or a son in paternal power. (3) With reference to both parties, the question arises, in accordance with the spirit of the law, whether the father can kill a magistrate, and also where his daughter is of bad reputation, or a wife has been illegally married, whether the father or the husband will still retain his right; and what should be done if the father or husband is a pimp, or is branded with ignominy for some reason or other. It may properly be held that those have a right to kill who can bring an accusation as a father or a husband. (Ulpian) It is provided as follows in the fifth section of the Julian law: 'That where a husband has caught an adulterer in the act of sexual intercourse with his wife, and is either unwilling or not allowed to kill him, he can hold him lawfully and without deceit for not more than twenty consecutive hours of the day and night, in order to obtain evidence of the crime.' (Ulpian) A woman cannot be accused of adultery during marriage by anyone who, in addition to the husband, is permitted to bring the accusation; for a third party should not annoy a wife who is approved by her husband, and disturb a quiet marriage, unless he has previously accused the husband of pimping (for his wife). (1) When, however, the charge has been abandoned by the husband, it is proper for it to be prosecuted by another.

Property Ownership The basic concept of property has two aspects: the object or thing itself and the social web of behavior and attitudes that recognizes a defined status relationship between the object and persons. Ownership status acknowledges the right to use or exercise control over an object or thing. The individual who holds such rights is termed the owner, proprietor or domini. In the Roman family this individual was the paterfamilias. The right is exclusive and controlling; it excludes nonowners from decisions regarding private property and the legitimate use or disposal of property without the express or tacit of the owner. If the status of an individual in relation to the use of an object or thing is such that he alone has the predominate priority in using or disposing of it, then the object becomes his "private property."

Cicero on Laws Marcus Tullus Cicero was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, and writer. He served as Roman Consul in 63 B.C. Here Cicero addresses Quintus with his opinions of the law. To Quintus: "But we must come to the true understanding of the matter, which is as follows: this and other commands and prohibitions of nations have the power to summon to righteousness and away from wrong doing; but this power is not merely older than the existance of nations and States, it is coeval with that God who guards and rules heaven and earth.....laws were invented for the safety of citizens, the preservation of States, and the tranquillity and happiness of human life; and that those who first put statutes of this kind in force convinced their people that it was their intention to write down and put into effect such rules as, once accepted and adopted, would make possible for them an honourable and happy life; and when such rules were drawn up and put in force, it is clear that men called them "laws".....It may thus be clear that in the very definition of the term "law" there inheres the idea and principle of choosing what is just and true.....And if a State lacks Law, must it for that reason be considered no State at all?.....Then Law must be considered one of the greatest goods."

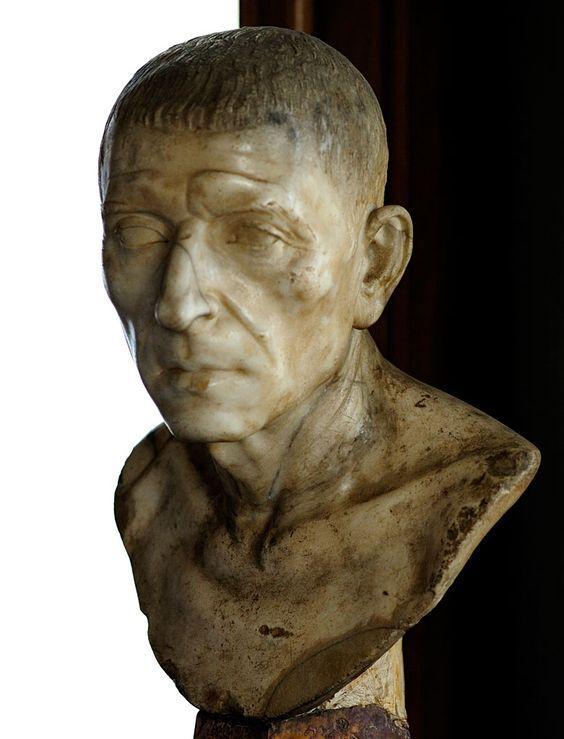

Bust of Cicero

The Law of the Twelve Tables The Law of the Twelve Tables was the earliest code of Roman law. It was formalized in 451-450 B.C. The Twelve Tables were written by the Decemviri Consulari Imperio Legibus Scribundis, (the 10 Consuls) who were given unprecedented powers to draft the laws of the young Republic. Originally ten laws were drafted ; two later statutes were added prohibiting marriage between the classes and affirming the binding nature of customary law. The new code promoted the organization of public prosecution of crimes and instituted a system whereby injured parties could seek just compensation in civil disputes. The plebeians were protected from the legal abuses of the ruling patricians, especially in the enforcement of debts. Serious punishments were levied for theft and the law gave male heads of families enormous social power (patria potestas). The important basic principle of a written legal code for Roman law was established , and justice was no longer based solely on the interpretation of judges. The Twelve Tables covered all catagories of the law and also included specific penalties for various infractions. The code underwent frequent changes but reamined in effact for almost 1000 years. These laws formed an important part of the foundation of all subsequent Western civil and criminal law.

- The following are the laws from the Twelve Table that pertain to family law specifically. Included are laws of inheritance (of wealth and debt), marriage, rights of fathers, and guardianship.

Table III: Debt

1-6. When debt has been acknowledged, or judgment about the matter had been pronounced in court, thirty days must be the legitimate time of grace. After that, then arrest of debtor may be made by laying on hands. Bring him into court. If he does not satisfy the judgment, or no one in court offers himself as surety on his behalf, the creditor may take the defaulter with him. He may bind him either in stocks or in chains; he may bind him with weight not less than fifteen pounds or with more if he shall so desire. The debtor, if he shall wish it, may live on his own. If he does not live on his own, the person [who shall hold him in bonds] shall give him one pound of grits for each day. He may give more if he shall so desire. On the third market day, creditors shall cut pieces (divide the debt?). Should they have cut more or less than their due, it shall be with impunity.

Table IV: Rights of fathers

1. A dreadfully deformed child shall be quickly killed.

2. If a father surrenders his son for sale three times, the son shall be free from his father.

4. A child born after ten months since the father's death will not be admitted into a legal inheritance.

Table V: Guardianship

1. Females should remain in guardianship even when they have attained their majority.

7a. If a man is raving mad, rightful authority over his person and chattels shall belong to his agnates or to his clansmen.

Table VI: Acquisition; possession.

Table XI: Supplementary laws

1. (Marriages) should not take place between plebeians and patricians.

Table XII: Supplementary laws

5. Whatever the people had last ordained should be held as binding by law.

Curia (Senate House of Ancient Rome-Where All Laws Were Passed and Ordained)

The Roman Republican Constitution The Romans never had a written constitution, but their form of government roughly parallels the modern American division of executive, legislative, and judicial branches, although the Senate does not fit into any of these categories. All the branches of Roman governent had a role in passing and ordaining laws that affected the Roman family.

EXECUTIVE BRANCH: The Elected Magistrates

- Consuls (2): chief civil and military magistrates; invested with imperium (power) greaterthen that of the Praetors; convened senate, curiate, and centuriate assemblies

- Praetors (2-8): had imperium; main functions included: military commands and administering civil law in Rome

- Aediles (2): plebian and curule; in charge of religious festivals, public games, temples, upkeep of the city, regulation of market places, and grain supply

- Quaestors (2-40): financial officers and administrative assistants; in charge of the state treasury in Rome

- Tribunes (2-10): charges with the protection of the lives and property of plebians; had power to veto (forbid) over elections, laws, decrees of the senate and the acts of other magistrates (except the dictator)

- Censors (2): elected every five years to conduct census, enroll new citizens, and review roll of senate; controlled public morals and supervised leasing of public contracts; in protocol ranked below praetors and above aediles; a position of high prestige and influence

- Dictator (1): in times of military emergency appointed by consuls; dictator appointed a Master of Horse to lead cavalry; tenure limited to six months or duration of crisis; not subject to veto

LEGISLATIVE BRANCH: The Three Citizen Assemblies

- Curiate Assembly: oldest of Rome; based on clan and family associations; eventually became obsolete as a legislative body but preserved functions of endowing senior magistrates with imperium ad witnessing religious affairs; the head of each curia was at least 50 years of age and elected for life

- Centuriate Assembly: most important unit of organization; membership based on wealth and age; elected censors and magistrates; a body for declaring war; passed some laws; served as highest court of appeal cases involving capital punishment

- Tribal Assembly: membership based on place of residence; elected lower magistrates; controlled by landed aristocracy (villa owners); eventually became chief law making body; presided over civil litigation - determined nature of suit, defined legal point or points at issue, and assigned case to be tried before a delegated judge or board of arbitrators; judge or arbitrators heard case, rendered judgement, and imposed fines

SENATE

- Originally and advisory board composed of the heads of patrician families, came to be an assembly of former magistrates

- The most powerful organ of Republican government and the only body of the state that could develop consistent long-term policy

- Enacted "decrees of the senate" which apparently had no formal authority, but often in practice decided matters

- Took heed of virtually all public matters; most important areas of provision were in foreign policy (including the conduct of war) and financial administration

Biblography Bradley, Keith R. Discovering the Roman Family, Oxford University Press: 1991. Crook, John. Law and Life of Rome, Cornell University Press: 1967. Dixon, Suzanne. The Roman Family, The John hopkins University Press: 1992. Dupont, Florence; translated by Christopher Woodall. Daily Life in Ancient Rome, Blackwell: 1994. Gardner, Jane F. Women in Roman Law and Society, Indiana University Press: 1986. Gardner, Jane F. and Thomas Wiedmann. The Roman Household: A Sourcebook, London: 1991. Lefkowitz and Fant. Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book In Translation, John Hopkins University Press: 1982. Rawson, Beryl. The Family in Ancient Rome, Cornell University Press: 1986. Rawson, Beryl and Paul Weaver. The Roman Family in Italy, Clarendon Press: 1997. Robbins, Sara. Law: A Treasury of Art and Literature, Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, Inc.: 1990. Schulz, F. Classical Roman Law, Clarendon Press: 1951.

Ancient References Cassius, History of Rome. Catullus, Poems. Cicero, Laws. Macer, Criminal Proceedings. Palpinian, On Adultery. Paul, Opinions. Pliny the Younger, Letters. Suetonius, Life of Augustus. Ulpian, Disputations. Ulpian, Lex Julia on Adultery. Ulpian, On Adultery.