The eclipse of the Roman Empire in the West (c. 395-500) and the German migrations

Invasions in the early 5th century

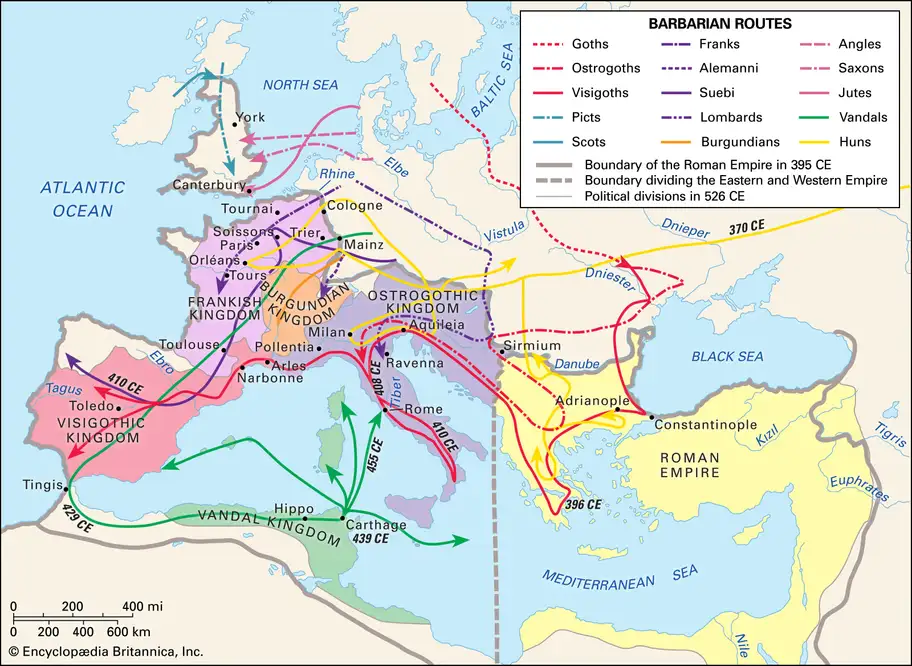

The barbarian invasions.

After the death of Theodosius the Western empire was governed by young Honorius. Stilicho, an experienced statesman and general, was charged with assisting him and maintaining unity with the East, which had been entrusted to Arcadius. The Eastern leaders soon rejected Stilicho's tutelage. An antibarbarian reaction had developed in Constantinople, which impeded the objectives of the half-Vandal Stilicho. He wanted to intervene on several occasions in the internal affairs at Constantinople but was prevented from doing so by a threat from the Visigoth chieftain Alaric, whom he checked at Pollentia in 402, then by the Ostrogoth Radagaisus' raid in 406, and finally by the great invasion of the Gauls in 407. The following year he hoped to restore unity by installing a new emperor in Constantinople, Theodosius II, the son of Arcadius, who had died prematurely; but he succumbed to a political and military plot in August 408. The division of the two partes imperii was now a permanent one.

Honorius, seated in Ravenna, a city easier to defend than Milan, had only incompetent courtiers surrounding him, themselves animated by a violent hatred of the barbarians. Alaric soon reappeared, at the head of his Visigoths, demanding land and money. Tired of the Romans' double-dealing, he descended on Rome itself. The city was taken and pillaged for three days, thus putting an end to an era of Western history (August 410). An Arian, Alaric spared the churches. He died shortly thereafter in the south; his successor, Athaulf, left the peninsula to march against the Gauls.

Fleeing from the terrifying advance of the Huns, on Dec. 31, 406, the Vandals, Suebi, and Alani, immediately followed by the Burgundians and bands of Alemanni, crossed the frozen Rhine and swept through Gaul, effortlessly throwing back the federated Franks and Alemanni from the frontiers. Between 409 and 415 a great many of these barbarians arrived in Spain and settled in Lusitania (Suebi) and in Baetica (Vandals, whence the name Andalusia). As soon as Gaul had become slightly more peaceful, Athaulf's Visigoths arrived, establishing themselves in Narbonensis and Aquitania. After recognizing them as "federates," Honorius asked them to go to Spain to fight the Vandals. Meanwhile, the Roman general Constantius eliminated several usurpers in Gaul, confined the Goths in Aquitania, and reorganized the administration (the Gallic assembly of 418). But he was unable to expel the Franks, the Alemanni, and the Burgundians, who had occupied the northern part of the country, nor to eliminate the brigandage of the Bagaudae. He was associated with the empire and was proclaimed Augustus in 421, but he died shortly afterward. His son, Valentinian III, succeeded Honorius in 423 and reigned until 455.

The beginning of Germanic hegemony in the West

During the first half of the 5th century the barbarians gradually installed themselves, in spite of the efforts of the Roman general Aetius at the head of a small army of mercenaries and of Huns. Aetius took back Arles and Narbonne from the Visigoths in 436, either pushed back the Salian and Ripuarian Franks beyond the Rhine or incorporated them as federates, settled the defeated Burgundians in Sapaudia (Savoy), and established the Alani in Orléans. The other provinces were lost: Britain, having been abandoned in 407 and already invaded by the Picts and Scots, fell to the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes; a great Suebi kingdom, officially federated but in fact independent, was organized in Spain after the departure of the Vandals, and it allied itself to the Visigoths of Theodoric I, who were settled in the country around the Garonne.

In 428 the Vandal Gaiseric led his people (80,000 persons, including 15,000 warriors) to Africa. St. Augustine died in 430 in besieged Hippo, Carthage fell in 435, and in 442 a treaty gave Gaiseric the rich provinces of Byzacena and Numidia. From there he was able to starve Rome, threaten Sicily, and close off the western basin of the Mediterranean to the Byzantines.

Shortly afterward, in 450, Attila's Huns invaded the West--first Gaul, where, after having been kept out of Paris, they were defeated by Aetius on the Campus Mauriacus (near Troyes), then Italy, which they evacuated soon after having received tribute from the pope, St. Leo. Attila died shortly afterward; and this invasion, which indeed left more legendary memories than actual ruins, had shown that a solidarity had been created between the Gallo-Romans and their barbarian occupiers, for the Franks, the Alemanni, and even Theodoric's Visigoths had come to Aetius' aid.

After the death of Aetius, in 454, and of Valentinian III, in 455, the West became the stake in the intrigues of the German chiefs Ricimer, Orestes, and Odoacer, who maintained real power through puppet emperors. In 457-461 the energetic Majorian reestablished imperial authority in southern Gaul until he was defeated by Gaiseric and assassinated shortly afterward. Finally, in 476, Odoacer deposed the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, had himself proclaimed king in the barbaric fashion, and governed Italy with moderation, being de jure under the emperor of the East. The end of the Roman Empire of the West passed almost unperceived.