Ming Dynasty to 1500

Rebellion against Mongol Rule

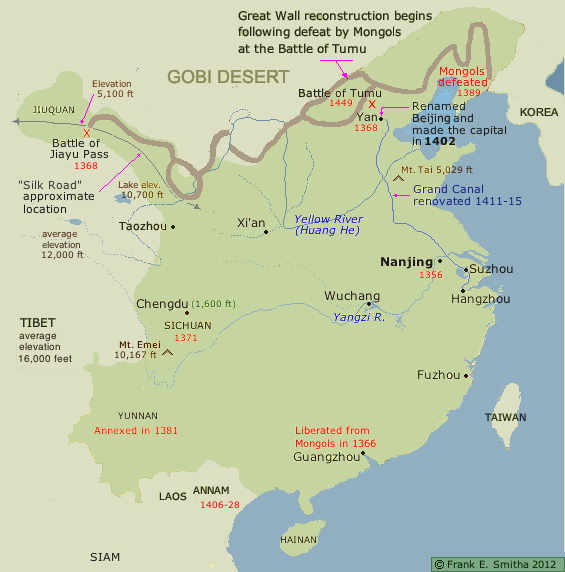

Jiayu Pass, built sometime around the year 1372 after Mongol troops were driven out in 1368. The fortress was strengthened following concern of an invasion by Timur that never came.

The Mongols in China were ruling with a great variety of administrators, military personnel and hangers-on – Turks, Arabs, a few Europeans, Jurchens and Persians. The Mongols were following their tradition of supporting a variety of faiths: Buddhism, Islam, Taoism and the Christianity that was practiced also by some of the Mongols in China.

China's Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, died in 1294 at the age of seventy-nine. His grandson, Temur Oljeitu, succeeded him, made peace with Japan and maintained reasonable prosperity. Temur Oljeitu was a conscientious and energetic emperor, but after his early death in 1307 he was followed by a nephew, Khaishan, who appointed people without talent to positions of government, including Buddhist and Taoist clergy, and he spent money lavishly on palaces and temples and tripled the supply of paper money.

Following Khaishan's death in 1311 his brother, Ayrubarwada, took power at age twenty-six. However competent Ayrubarwada was as a ruler, opposition rose against him at court by those who saw him as too sympathetic with the Chinese. He died in 1320, and his eldest son, Shidebala, succeeded him at the age of eighteen. Shidebala initiated anti-corruption reforms, sided with Tibetan Buddhists against Muslims and was assassinated in 1323.

Shidebala was succeeded by Yesun Temur, who was oriented toward Mongol traditions. His supporters had been involved in the assassination of Shidebala, and he distanced himself from them and returned to the Mongol tradition of treating religions impartially.

Yesun Temur died in 1328 and the youngest son of Khaishan, Tugh Temur, 24-years-old, took power. He was skilled in Chinese. He was a painter, supported education, lived modestly and dismissed over 10,000 from the imperial staff.

Following Tugh Temur's death in 1332, a thirteen-year-old, Toghun Temur, became nominal emperor. His ministers ran state affairs. His first minister was concerned with what he saw as Mongol weakness in China. He re-imposed segregation between the Mongols and Chinese, decreed that Chinese were not to learn Mongolian, confiscated weapons and iron tools from the Chinese, outlawed Chinese opera and storytelling, and he considered exterminating Chinese.

Rebellion and the Ming

During Toghun Temur's rule, Chinese opposition to Mongol rule was on the rise. The Mongols were different from the Chinese not only in speech but in dress and other habits, and the Chinese looked upon the Mongols as barbarians. They disliked Mongol table manners, and they thought the Mongols smelled(Mongols culture excluded frequent bathing – the result of their living with a scarcity of water. They saw lake water as holy and washing clothes in it as pollution).

Across decades of peace, the ability at warfare of the Mongol warriors had been declining. Common Mongol troops had been put to work farming to support themselves, using slaves. Some of these Mongol warriors had failed as farmers and had lost their farms. Some had become vagrants, while Mongol army officers remained as a salaried aristocracy segregated from the common Mongol soldier.

In 1346, plague had broken out among Mongols in the Crimea, and the plague spread to Mongols in China. Also there were floods that disrupted the country. Mongol military garrisons continued to rule at strategic points in China, but the Mongols were greatly outnumbered and were not prepared to contend with a great rebellion. Mongol military commanders began running the government, and Toghun Temur, now in his late twenties, passed into semi-retirement. He is reported to have taken pleasure only in boy catamites and in prayer with Buddhist monks from Tibet. Toghun Temur's debauchery and his devotion to Tibetan Buddhism added to Confucianist grievances, and opposition to Toghun Temur arose also among Buddhists. A secret Buddhist sect, the White Lotus, began organizing for revolution and prophesied the coming of a Buddhist messiah, Maitreya.

Mongol rule in China was about 76 years-old when, in 1352, a rebellion took shape around Guangzhou. A former boy beggar boy who associated himself with a Buddhist temple but never actually became a monk, Zhu Yuanzhang, left his temple and joined the rebellion, and his exceptional intelligence took him to the head of a rebel army. By 1355 the rebellion, accompanied by anarchy, had spread through much of China. Zhu Yuanzhang won people to his side by forbidding his soldiers to pillage. In 1356, Zhu Yuanzhang captured Nanjing and made it his capital, and there he won the help of Confucian scholars who issued pronouncements for him and performed rituals in his claim of the Mandate of Heaven. And Zhe Yuanzhang defeated other rebel armies.

Meanwhile, Toghun Temur was still emperor, and during the rebellion in the mid-1350s the Mongols were fighting among themselves, inhibiting their ability to quell the rebellion. By 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang had extended his rule to Guangzhou – the same year that Toghan Temur fled to Karakorum. Zhu Yuanzhang and his army entered the former Mongol capital, Beijing, and with this he claimed the Mandate of Heaven. In 1371 his army moved through Sichuan. By 1387 – after more than thirty years of war – Zhu Yuanzhang had freed China of Mongol rule, and as China's emperor he founded a new dynasty: the Ming.

Expansion and Withdrawal

The Grand Canal today at Suzhou

The first concern of China's new Ming emperor in 1370 was military strength and preventing Mongol resurgence. The emperor, Hong-wu, established garrisons at strategic points and created a hereditary military caste of soldiers who would sustain themselves by farming and be ever-ready for war. Troops were forbidden to abuse civilians. Hong-wu made his commanders a new military nobility. Hong-wu's standing army exceeded one million in number, and his navy's dockyards in Nanjing were the largest in the world.

Farms had been devastated and he settled a huge number of peasants on what had been wasteland and gave them tax exemptions. Hong-wu attempted to create a society of self-sufficient rural communities. Between 1371 and 1379 the land under cultivation tripled, as did revenues. The government sponsored tree planting and reforestation. Neglected dikes and canals were repaired and thousands of reservoirs were rebuilt or restored. During his reign, China had a dramatic population growth, explained as due to an increased food supply and Hong-wu's agricultural reforms.

Hong-wu was tough on opponents. His regime executed anyone who violated his laws or were suspected of treason. He banned secret societies. He increasingly feared rebellions and coups, and he made it a capital offence for any of his advisors to criticize him. He became infamous for killing many people during his purges. His regime has been described as using many tortures, including flaying and slow slicing. In 1380, according to Wikipedia, a lightning bolt struck his palace and he stopped the massacres "for some time" while afraid of punishment by "divine forces."

Hong-wu considered the destructive role of court eunuchs under previous dynasties, and he reduced their numbers, forbade them to handle documents, insisted they remain illiterate and executed any who commented on state affairs.

Hong-wu died in 1398, at the age of seventy, and his death was followed by four years of civil war and the disappearance of his son and heir, Jianwen. Jianwen had been indecisive and scholarly and no match for his uncle, the Prince of Yan, who in 1402 became Emperor Yongle (meaning Perpetual Happiness) and made Yan his capital and renamed it Beijing.

In the wake of Mongol rule, China's leaders were eager to restore things Chinese, and that included shipping on China's canals – which had fallen into disrepair under the Mongols. According to Wikipedia, between 1411 and 1415 a total of 165,000 laborers dredged the canal bed in Shandong Province, and they built new channels, embankments, and canal locks.

One of Emperor Yongle's eunuchs, Zheng He, was a Muslim whose father had made a pilgrimage to Mecca. Zheng He knew the world a little more than others, and he led a group of can-do eunuchs that performed special tasks for the emperor, and Emperor Yongle ordered Zheng to make naval expeditions.

From the Mongols the Ming rulers had inherited extensive maritime contacts and technology. During Mongol rule, large Chinese cargo ships had plied the oceans around China, including a regular run of grain from the south along the coast to the north. And Chinese ships had traded through southeast Asia to the island of Lanka (Sri Lanka) and to India. But the Ming dynasty did not maintain this trade. Zheng He's expedition, beginning in 1405, was made for the sake of geographical exploration and diplomacy – an expedition with sixty-three ships and 27,000 men. Six more expeditions led by Zheng followed, continuing after the death of Emperor Yongle in 1424. The last expedition was in 1433 under Emperor Xuande, grandson of Emperor Yongle. The expeditions reached Surabaya at the island of Java, and they reached India and then Mogadishu on the coast of Africa, Hormuz at the Persian Gulf, and up the Red Sea to Jeddah. Gifts were exchanged, and rare spices, plants and animals, including a giraffe, were brought back to China.

China had the world's greatest navy, with an estimated 317 ships – constructed at Nanjing. These ships were made with special woods and waterproofing techniques, and they had an adjustable centerboard keel. Some of the ships were 440 feet long and 180 feet wide, ships with four to nine masts that were as high as ninety feet, with silk sails and with crews that numbered as many as five hundred.

But in China interest in a great navy and merchant shipping was overshadowed by concern about military defenses on land. Attempts to control Annam failed and were expensive. In the mid-1400s the Mongols were making border raids and appeared to the Chinese as a greater threat. Also, Confucian influence had increased at court. Confucian scholars were filling the ranks of senior officialdom and remained hostile to commerce and foreign contacts. The Confucianists had little or no interest in seeing China develop into a great maritime trading power. The Confucianists saw internal trade as enough. The government ended its sponsorship of naval expeditions, and, in the spirit of isolationism, the government forbade multi-masted ships sailing out of port. The development of world maritime trade was left to Europeans, who were now beginning to extend their voyages.

Meanwhile, Confucian ideology was inhibiting commercial enterprise.

Sources

The Rise and Splendor of the Chinese Empire, by René Grousset, 1968

China: a New History, by John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, 1998

The Ageless Chinese by Dun J. Li, 1978