Ancient Romans were great seafarers. The Roman Navy played a vital, if not overly glamorous, role in keeping the Republic and later the Empire safe from various external forces. It saved the Romans during the Punic Wars, brought final victory to Octavian, who would go on to become the first Emperor of Rome, and allowed the Romans to call the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum - "Our Sea," by keeping it free of piracy. The Romans always maintained a dislike for the sea, yet they remained dependent on it for trade and commerce, and were thus forced into keeping a strong hold on it by keeping up a strong navy.

The most basic naval warfare tactic used by the Romans and all ancient seafaring nations was to ram an enemy vessel. then send marines aboard to slaughter the survivors. This required oarsmen who were in excellent physical condition and who had for many long hours practiced the teamwork and split-second timing that made the difference between a quick victory and a floundering, clumsy defeat.

The Romans, since the earliest times, had not been known as great seafarers. This they left to the intrepid Phoenicians, Greeks, and later, the Carthaginians. They fought all of their battles on land, being much more comfortable on solid ground. By 272 BC, the whole of the Italian peninsula south of the Po River was in Roman hands.

However, Roman expansion soon brought them into conflict with the great maritime power of the age, Carthage. The Carthaginians, rich from trade, were able to support huge fleets by the standard of the time. This allowed them to take a virtual monopoly on trade in the western Mediterranean. Rome at this time was expanding as both a nation and a city; with the conquest of Magna Graecia, the Greek cities of southern Italy, they became aware of the prosperity available from trade. They also needed to guarantee regular shipments of grain to feed the populace, which could be supplied by the fertile fields of Sicily.

Thus, when separate factions in the city of Messana, strategically located on the straits separating Sicily and Italy, appealed first to Carthage and then to Rome for help against each other, in 146 BC, Rome could not sit idly by. What is now referred to as the First Punic War began. After an affirmative vote by the people of Rome to help the Messenians, the Romans ferried their troops across the straits on borrowed vessels). The Roman legions met with early successes on the landward parts of Sicily, but at the same time the superior Carthaginian fleets ravaged the coasts of both that island and the Italian peninsula. It soon became apparent that mastery of the seas was of paramount importance if Rome were to progress further.

Chiefly from the accounts of the Greek historian Polybius, we learn that the Roman Senate now ordered the construction of 120 warships. This was not the beginning of the Roman navy, as small contingents recruited from Magna Graecia had provided a flotilla of small, second-class ships from around 282 BC. It did, however, mark the emergence of Rome as a naval power in the Mediterranean. The 120 ships were made up of two classes, as Polybius tells us, 20 triremes and 100 quinqueremes. The former were of the same basic design that had been in use by the Greeks for 500 years. They were arranged with three levels of oars on each side, the top level containing 31 oars rowed by one man each and the other two levels containing 27 each . The heyday of the trireme, however, had ended. The second type of ship in the order, the quinquereme, would make up the majority of the fleets of both sides during the three Punic Wars.

The quinquereme or "five", Lat. penteres, represented a major advance over the trireme. Dionysius I, a tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily, is credited with its invention along with that of the oar system that made it possible Ships. Previously, as in triremes, each oar was rowed by one man. Dionysius conceived oars rowed by two or more men. This allowed the construction of "fours," "fives," and higher rated ships, even though the maximum workable number of oar levels was three. A quinquereme could have three levels of oars, the top two possessing oars rowed by two men each, and the bottom by one.

Alternatively, it could have two levels, the top rowed by three men to an oar, the bottom by two. A third option is a single level of oars, each oar worked by five men. It is this third arrangement that benefited the Romans. Each individual oar on a galley must be worked by at least one trained rower, so that it does not foul the other oars. The Romans, having almost no naval experience, would be faced with a severe shortage of trained crews, considering that a standard Carthaginian "five" on the 2-2-1 system needed 160 skilled rowers, and the Roman fleet was to consist of 100 "fives," the total number of trained oarsmen coming out to be 16,000. But with the one level five, only 5,400 trained men were required.

Of course, 21,600 other men were also needed to row, but they would have been much easier to acquire . Polybius tells the story of a Punic quinquereme, beached on a shore in Italy, coming into the hands of the Romans, and giving them a model on which to base their fleet. However, in light of the above case, this seems unlikely.

The Romans trained the crews on rowing machines during the sixty day period it took to construct the fleet. However, they were still no match for the Carthaginians in seafaring skill. The standard tactic of the day was ramming the opponent to put a hole in his side with the bronze encased ram on the prow of every warship. This required a great deal of skill, as the window for a successful ram attack was in the area of eight seconds, and that only if the crew was skilled enough to make last-second corrections, as a vessel arriving early was in danger of being itself rammed by its prey. A second option was to make as if to ram, and then turn away, attempting to shear off the enemy vessel's oars, immobilizing it.

In the spring of 260 BC, the Roman fleet had been completed and outfitted, and set off down the coast of Italy toward Sicily. One of the two consuls, Gaius Cornelius Scipio, who had been chosen to command the fleet, sailed to Messana with 17 ships in order to prepare for the arrival of the rest of his command. He then proceeded to seize the Lipari Isles, about 30 miles northwest of Messana. The Carthaginians learned of his presence there from their base in Panormus, and dispatched 20 ships under Boodes to engage Scipio. Boodes came upon the Romans unawares, and the inexperienced crews abandoned their ships and commander, leaving them to be captured by the Carthaginians.

After this small victory, the Carthaginian admiral, Hannibal, who, it may be worth mentioning, was not the same as the one famous for his elephantine exploits, sailed toward Italy with 50 ships, with the intention of observing the Roman fleet. He was surprised by the Romans while rounding a cape. According to Rodgers, he came away with few losses, but Shepard alleges that he lost over half of his forces and barely escaped with his own life . The other consul, Duilius, previously in command of the land forces, upon hearing of the capture of Scipio, instead assumed control of the fleet.

The Romans found, in the course of these first two skirmishes, that they lacked the seamanship and necessary skill to outperform the Carthaginians. However, someone in the Roman camp, perhaps from the seafarers of Magna Graecia, came up with a solution that would allow the Romans to benefit from their experience with land warfare. This was the "crow" or "raven", Latin corvus, a 35 foot long bridge mounted on a swivel so that it could be turned and dropped on an adjacent enemy vessel. A large spike at the end of the corvus bit into the other ship, locking the two craft together. Then the Roman marines, who were in a larger proportion to the crew than on Carthaginian ships, would storm across and engage the enemy crew, usually resulting in a Roman victory.

The first major engagement of the war occurred off Mylae, west of Messana and south of Lipari. Admiral Hannibal had been plundering the shore near there, hoping to draw the Romans out to battle. He was confident that superior Carthaginian tactics and proficiency in rowing would make for an easy victory. His ships advanced recklessly toward the Roman line. However, the Romans had equipped their quinqueremes with the corvus and packed them full of marines. The Punic ships, including the flagship of Hannibal, a "six", upon coming into range, soon fell prey to this tactic. The Carthaginian admiral escaped in a small boat, but he had lost 50 ships by the end of the battle. The Roman admiral, Duilius, was awarded many honors, including the right to be escorted by torch bearers and flute players when returning from banquets.

The next year, 259 BC, the consul Lucius Scipio led the fleet to Corsica, capturing it for Rome, and destroyed a Punic squadron under the hapless Hannibal consisting of 60 ships in harbor in Sardinia. For this defeat, the Carthaginians crucified their admiral. The year after this occurrence, the Roman consul Gaius Sulpicius was successful in leading a fleet to the African coast, defeating a small opposing force, and plundering several littoral settlements.

The Romans had little success on land in Sicily, as their fleet did not have the range to give the type of support needed against the Carthaginian strongholds. Ancient fleets of any substantial size needed a close base to work from, but the western part of Sicily was firmly in Carthaginian hands. In 257 BC the Roman fleet under Atilius Regulus raided Melita, now Malta, and returned to Sicily. At Tyndaris, to the west of Mylae, the Romans sank eight and captured ten Carthaginian ships, with the loss of ten themselves . Shipbuilding efforts continued by both sides throughout.

By the beginning of the sailing season in the spring of 256 BC, the Romans were ready to invade Africa. Polybius, as recounted by Shepard, gives their numbers at 330 quinqueremes plus a number of horse transports. Rodgers describes these figures as "impossibly large". He suggests, following the estimates of W.W. Tarn, 250 warships and the rest of the 330 being made up of the transports. He similarly amends Polybius' 350 Carthaginian vessels to 200. The Roman fleet under the consuls of the year, Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius Vulso, set sail from Messana, rounded the southeastern tip of Sicily, and headed west along its coast.

The Punic fleet under Hamilcar and Hanno was waiting at Heraclea, knowing the Romans would have to pass their position to get to Africa. The Romans sailed west until they came to Mount Ecnomus, where their army was encamped. They loaded their troops onto the quinqueremes, in order to once again use the boarding tactic. Necessary supplies, such as horses and field artillery were loaded on transports. The Roman warships were slower than the Carthaginian ones, due to their inferior crews, and they were encumbered by the necessity to guard the defenseless transports.

Hamilcar sought to exploit this advantage and attempt to take out as many transports as possible. He understood that if he could capture or destroy enough of these, the Romans would have no choice but to retreat. The Romans also understood this, and deployed their ships in a defensive triangle, with the transports towed by warships in the center, and a fourth group making up the rear. The consuls Regulus and Manlius, in "sixes," took positions at the point of the triangle facing the Carthaginian line. Hamilcar drew the Punic squadron into four columns, leading the center two himself, and Hanno commanded his right. He planned to envelop the Romans and prevent the escape of the transports.

The two sides of the Roman triangle led by the consuls moved forward into a line and advanced toward Hamilcar and the Carthaginian center. The Roman transports were severed from their tows and began fleeing back toward the Roman camp. The warships thus freed moved right toward the shore to meet the advance of the Punic left. The fourth Roman squadron took a position where it could intercept Hanno if he attempted to pursue the transports or come upon the consul's groups from the rear. Three small battles developed as these groups met the enemy.

The consuls were victorious against Hamilcar, and Regulus turned back to aid the Romans facing Hanno. The Roman right was driven back against the shore, but Manlius, the other consul, took his ships to strike the rear of the Carthaginians attacking it. He was soon joined by Regulus, who had made quick work of Hanno's squadron. Several Carthaginian ships escaped being taken from all sides, but many did not. The Romans had scattered the Punic fleet, sunk 30 ships and captured 64 vessels intact. The Carthaginians had only managed to sink 24 Roman ships before being routed.

The Romans successfully landed in Africa, and, winning several victories, found themselves in Tunis, only twelve miles from Carthage itself. Regulus nearly obtained a Carthaginian surrender, but at that time a Spartan mercenary named Xanthippos came into Punic pay, and soundly defeated the Roman consul, capturing him. A fleet numbering 350 was sent from Sicily to rescue the survivors. The Carthaginians, confident from their victory, attacked and lost, according to various accounts, 114 or 24 ships, in either case being defeated.

The Romans began returning to Sicily with the prizes and the survivors, but were caught in a gale to the south of the island. All but eighty of their ships were destroyed. They constructed 140 new vessels, and by a combined attack of land and sea, captured the Carthaginian garrison at Panormus. After this, Shepard says that half of the fleet was wrecked in a storm, while Rodgers writes that only 27 were lost. Starr notes that, over the course of the war, around 600 warships and 1000 transports were sunk, between battle losses and those caught in storms. He establishes a connection between storm losses and the corvus, which made the ships top-heavy and vulnerable to poor weather.

In 250 BC, the Romans sailed to Sicily with 240 ships loaded with troops to besiege the Carthaginian town of Lilybaeum, on the western tip of Sicily. The town had excellent natural defenses, and could not be taken by outright assault. The Romans laid siege to it by land, and blockaded the harbor with 200 ships. The Carthaginians sent a relief force of 10,000 men on 50 ships. The admiral in charge of this force, another Hannibal, employed an unusual but successful tactic. He moved toward the harbor with sails up. In naval battles, sails were almost always taken down, to improve maneuverability and because of the risk of the mast snapping from the impact of ramming. With favorable wind, he was able to sweep right by the Romans, who were afraid to risk the impact caused by such relatively high speeds, and were also limited by their slower ships which would have had some difficulty catching the Carthaginian ships.

The Punic garrison inside Lilybaeum was greatly heartened by the successful reinforcement. Later that year, another blockade run was made, again by a Hannibal, this one nicknamed "the Rhodian." His ship was considerably faster than the Romans', and he made several successful trips into and out of the harbor. However, the Romans captured a slower vessel and sunk it in the harbor mouth. With this tactic they were able to capture the Rhodian and his vessel. With the swift ship they had less trouble with blockade running. The siege would drag on for nine more years.

Meanwhile, the main Carthaginian fleet under Adherbal waited at Drepanum, sending out swift ships to again harass the Sicilian and Italian coasts. In 249 BC, one of the current consuls, Publius Claudius, set out with 10,000 fresh men to augment the crews and 123 ships to surprise Adherbal. Claudius was a rash and inexperienced commander. Before the battle, it was reported to him that the sacred chickens, from which the omens would be taken, refused to eat. He responded, famously, that if they would not eat they could drink, and ordered them thrown overboard. This set the tone of the day. The consul planned to take the enemy unawares in the harbor at Drepanum. He succeeded with this part of his strategy.

The next part, however, was to sail into the harbor to attack. Adherbal swiftly readied his ships and advanced to meet the attack. Claudius, commanding from the rear of the Roman line, upon hearing of this, relayed the order forward to withdraw. By this time, his front had entered the narrow harbor entrance, and many ships became entangled and confused. Adherbal made quick work of them. Claudius, meanwhile, was leading the retreat.

The Carthaginians caught up with him, and he backed his ships against the shore, a tactic that had worked at Mount Ecnomus. However, his ships were not equipped with the corvus, and the proximity of the shore made for less room to maneuver. The results were disastrous. The Carthaginians sunk 97 Roman ships and captured 93, with 20,000 prisoners. Diodorus, a decidedly pro-Carthaginian Greek historian, says that the Adherbal lost only several ships, which originally numbered less than half of the Roman fleet.

After this loss, the Romans let their navy languish for several years, concentrating instead on land-based efforts. But it appeared that Lilybaeum could hold out as long as Carthage sent supplies, and these could be delivered by sea. In 247 BC, Hamilcar Barca, father of the famous Hannibal, took command of the Carthaginian forces. He took advantage of the Roman lapse and sent large fleets to pillage the Italian and Sicilian coasts. Making no progress on land, the Romans looked again to their fleets.

However, the treasury was exhausted, and private citizens covered the expenses of 200 new quinqueremes. These were not equipped with the corvus, which was never used again. Under the command of the consul Gaius Lutatius Catulus, they sailed for Sicily in the summer of 242 BC. He aided the siege of Lilybaeum, and kept his crews in top shape. The Carthaginians were surprised, as their fleets had returned to Africa for the year. They set out from Carthage fully loaded with supplies to reinforce the besieged city.

Catulus stationed his forces in the Aegates Islands, several miles west of Lilybaeum, and awaited the arrival of the Punic fleet, under the leadership of Hanno. On the day of the battle, the wind and sea favored the Carthaginians. Hanno hoped to use the same tactic Hannibal had previously used, and move past the Romans with full sails. However, as a result of keeping his crews trained, Catulus felt confident enough to risk battle. His ships were faster, their crews being in better shape, and they were full of marines, whereas Hanno's fleet was so full of supplies that it was sluggish and had little room for troops. It was a quick Roman victory, and they sank 50 and captured 70 Carthaginian ships. Upon his return to Carthage, Hanno was crucified .

This battle isolated the Carthaginians in Sicily, and Hamilcar met with Catulus to discuss terms of peace. Carthage ended up paying 3,200 talents, enough to reimburse the citizens who had financed the last fleet of quinqueremes, leaving Sicily to the Romans, and returning all Roman prisoners. The First Punic War was one of, if not the, most navally-oriented wars in the ancient world. It crushed the Carthaginian mastery of the sea, and brought Rome onto the Mediterranean stage. It showed the advantage of the patriotic but smaller and poorer Roman state over the wealthy and powerful but mercenary-reliant Carthaginians. It gave Rome her first taste of empire, and in so doing changed the course of history.

The Parts Of The Ship

These were the basic parts of the Roman Quinquireme, an long, slender warship propelled by rowers and on occasion by sail and suited for naval combat on the Mediterranean during Classical times.

Corvus

This movable gangplank could be swung out over the side of a Roman ship during battle and dropped on the deck of the enemy ship. Then, Roman soldiers could rush aboard the enemy ships, taking the enemy sailors by complete surprise and cutting them down with their deadly short swords. Roman engineers were always making improvements in the things they borrowed (or took by force) from their neighbors. This improvement on the design of the Carthaginian trireme helped the Romans to sweep the Carthaginian navy from the seas and win the First Punic War, fought with Carthage from 264 to 241 B.C.

Beak

The heavy, bronze reinforced ram or beak was the only weapon of ancient tomes that could sink a ship. Cannon hadn't been invented yet, and land based siege catapaults, which could hurl heavy stones over the wall of a fort, were too heavy and clumsy to be used aboard ships of that day. The men at the oars were made to row as hard as they could, then the ship was turned toward the enemy's broadside. The stout armored ram would tear a hole in the enemy ship's hull, letting the sea in to drown the hapless men caught belowdecks. With the ship mortally wounded, the Roman soldiers leapt upon the remainder of the enemy who still had any fight left in them and quickly put an end to the engagement. Sometimes, if the enemy were stouthearted and experienced warriors who managed to get the upper hand, they might turn things around and capture their attackers’ship!

Towers

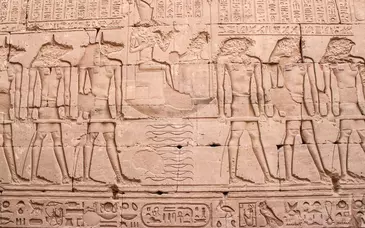

Sometimes towers were built on Roman vessels used in war. There are several monuments that have reliefs carved into their sides showing this feature. Most historians believe they were used as a place where archers could shoot their arrows at enemy seamen in the clear above the heads of their shipmates. They may also have been used as a platform from which heavy stones or burning pitch were hurled on an enemy's decks.

Gunwales

The sides, or gunwales of the Roman warship were usually lined with the soldiers' shields. These were often highly decorated with Gorgon's heads or other designs. They also usually carried the unit colors or insignia. You could often tell from a distance which cohort a legionary belonged to by looking at the design on his shield

Oars

The oars were rowed by Roman soldiers (not usually by slaves, as is commonly believed) and were the primary means of propelling the ship through the water during a battle. It took strong, willing men at the benches to drive the trireme fast enough to cut a hole in an enemy hull with her ram.

Rudder

Unlike modern ships, the Roman trireme was steered with a large oar that hung out over the side near the stern (rear) of the ship. Even though it seems quite crude by our standards, the steering oar was really quite efficient for these ships which seldom exceeded 150 feet in length and were used primarily on the Mediterranean Sea during daylight hours.

Sail

Roman warships had two different and independent propulsion systems, or energy sources used to move the ship. Oars were used in calm weather and when going into battle. The sails were used when the wind was blowing in the right direction and not too strong. During the later Roman period, Roman sailors did learn to sail across the wind instead of simply sailing downwind. They never learned to be great naval engineers and innovators like the Greeks and Phoenicians. Their attitude was "Just give me a ship good enough to do the job." They never really adopted naval tactics, either, preferring to wage a sea battle by ramming and boarding the enemy, then using land tactics. When the time for battle drew near, the mast was stepped (taken down) and both mast and sails were stowed (put away).

Roman Seamen

Contrary to what has been depicted in such great Hollywood movies as Cleopatra and Ben Hur, most men at the rowing benches of Roman warships were ordinary legionaries who preferred fighting on land. Though they often grumbled when their commanders required them to row a warship and spend long, seasick months training for an impending sea fight, these true Roman soldiers pitched in and did their part. After all, their lives depended on their ability to row and almost everyone preferred death standing on his two feet in a land battle to a cold, watery grave!