Archaeological investigations in the Middle East are uncovering the intriguing ways in which an ancient, long-forgotten civilization employed previously unknown linguistic practices to foster multiculturalism and political stability. These groundbreaking findings, emanating from ongoing excavations in Turkey at the ruins of the Hittite empire's ancient capital, are providing fresh insights into the functioning of early empires.

Within the remnants of Hattusa (now known as Bogazkoy), evidence is emerging that the imperial civil service included specialized departments dedicated to researching the religions of subject peoples. In a fascinating twist, Hittite leaders instructed their civil servants during the second millennium BC to document the religious liturgies and traditions of subject peoples in their respective local languages (albeit in Hittite script). This approach aimed to preserve and integrate diverse traditions into the empire's inclusive multicultural religious system.

Modern experts in ancient languages have identified preserved religious documents from at least five ethnic groups, including the recent discovery of a previously unknown language, Kalasmaic, lost for up to 3,000 years. Approximately 5 percent of the unearthed clay tablet documents were inscribed in languages of minority ethnic groups, such as the Luwians, Palaians, Hattians, and Hurrians.

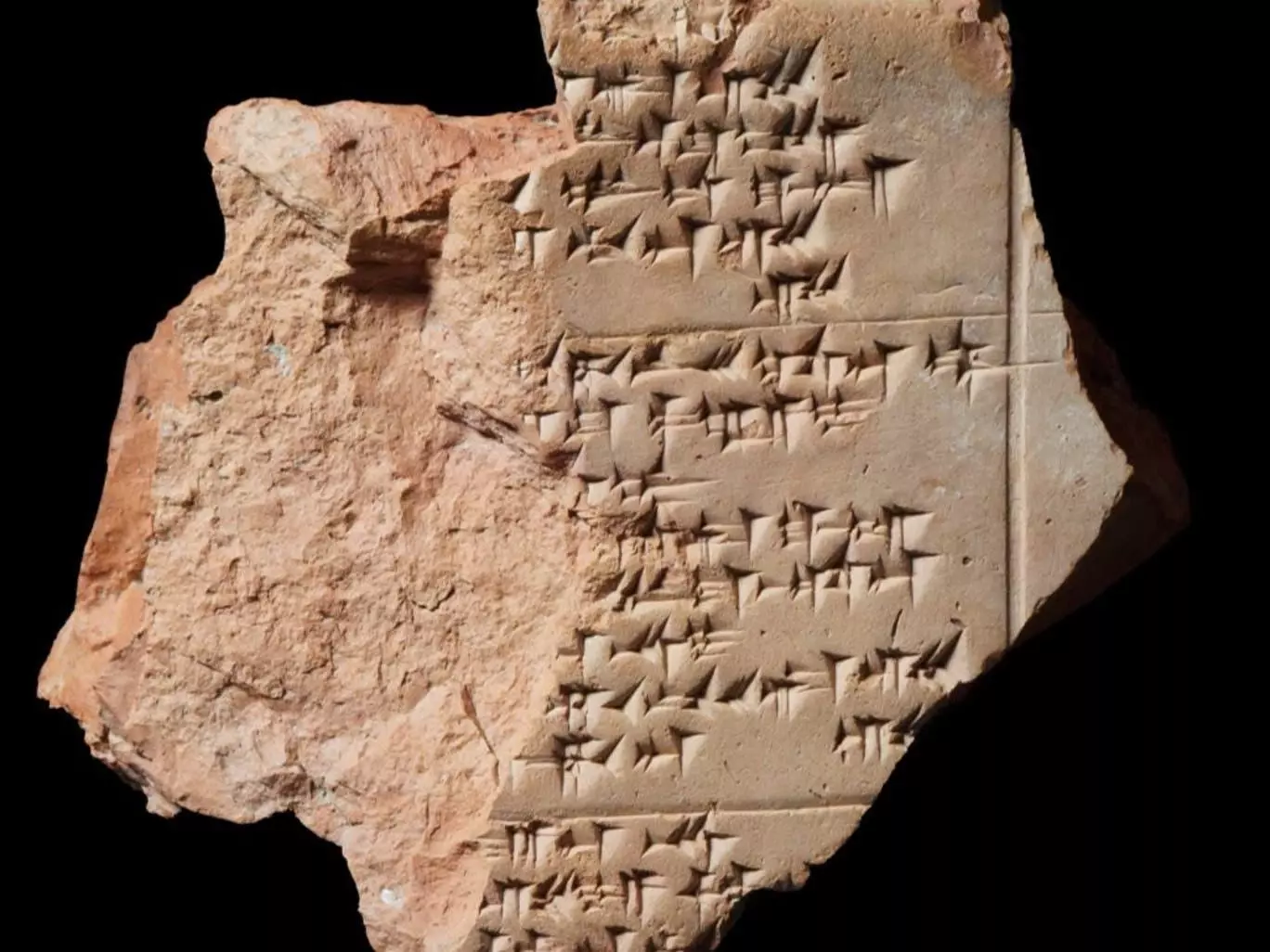

The Hittite civil service meticulously recorded these manuscripts in cuneiform, a script derived from a pre-existing Mesopotamian-originating script, showcasing linguistic diversity in the ancient Hittite Empire. The region, now Turkey, was historically rich in languages, a phenomenon influenced by its topography—mountains and isolated valleys contributing to the development and survival of numerous languages.

Despite currently only knowing of five minority languages from the Bronze Age Hittite Empire, the mountainous terrain suggests there may have been many more—potentially around 30. Adjacent to the Hittite Empire were the Caucasus mountains, which still hosts around 40 languages today.

The Hittite language itself stands as the world's oldest attested Indo-European tongue, with inscriptions dating back to the 16th century BC. The ongoing excavations at Bogazkoy, led by Professor Andreas Schachner of the German Archaeological Institute, along with paleo-linguists from Wurzburg and Istanbul universities, offer a unique opportunity to understand the evolution of ancient Bronze Age Indo-European languages.

As cuneiform tablets continue to be unearthed at a rate of 30 to 40 per year, these findings contribute significantly to our understanding of Bronze Age Middle Eastern history. Professor Daniel Schwemer of Wurzburg University, a cuneiform script expert, emphasizes the importance of these discoveries in expanding our knowledge of the Hittite civilization and its transformative impact on human history. The Hittite Empire, stretching from the Aegean Sea to northern Iraq and from the Black Sea to Lebanon, played a pivotal role in shaping human history through technological innovations and the establishment of substantial civil services.