Below are photographs and descriptions of buildings and places as they are today. Buildings that were constructed after Paul's time are still addressed, so keep in mind that Paul would not have seen such architectural structures as the Library of Celsus and the Temple of Hadrian. Click on an image below (thumbnail) to view a larger version of it.

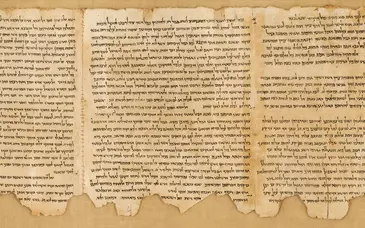

The archaeological record in Ephesus is rich. There have been many items found in this site, such as pieces of statues, sarcophagi, relief sculptures, and architectural fragments, which we will not investigate here (Cf. Smith, 171-200). Also, the epigraphy of Ephesus is equally noteworthy; Oster mentions that the site has yielded more than 4,000 Greek and Latin inscriptions (Oster Bibliography, xvi).

Locating Ephesus

Ephesus was located on the Western coast of Asia Minor, in the province of Asia.

The following map is adapted from Michael D. Coogan ed., The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Third Edition (Oxford: 2001).

The Site Plan of Ephesus

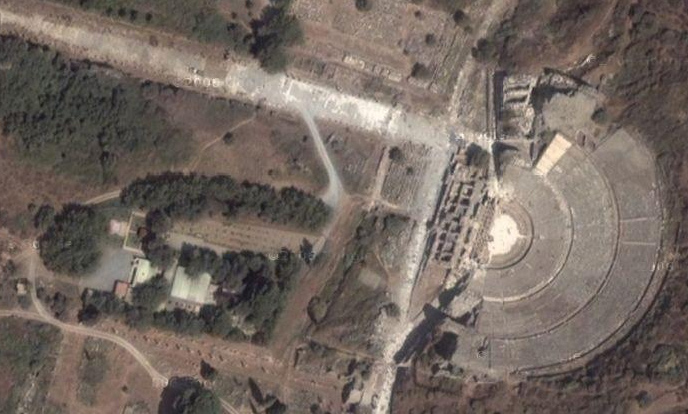

The archaeological remains of Ephesus are clearly shown in the satellite image.

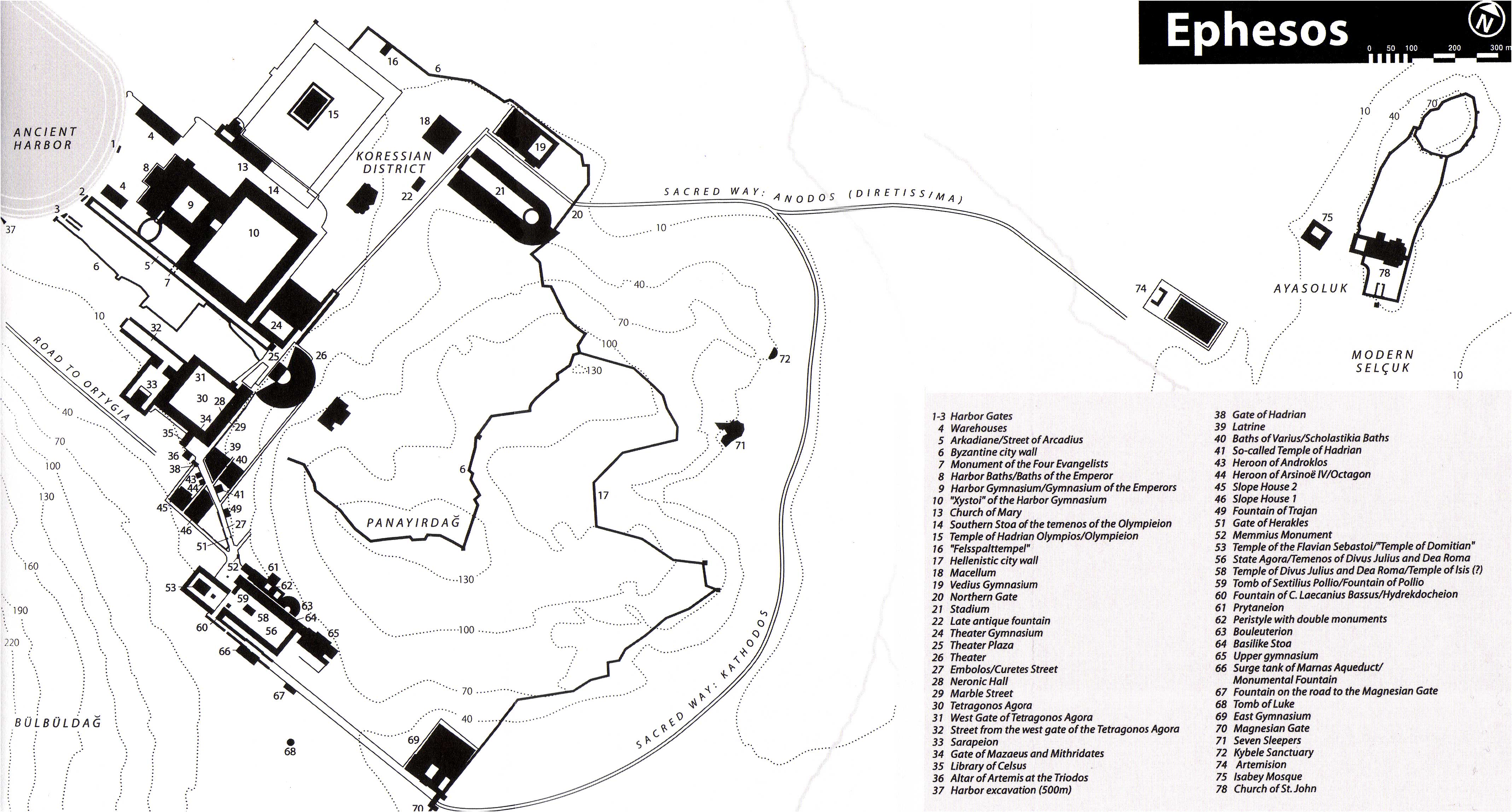

The following is a detailed site map of the city.

Image from the back of Helmut Koester, Ephesos: Metropolis of Asia (Cambridge, MA: 1995).

Aqueduct

During the Augustan age, Ephesus grew remarkably and was a recipient of the general prosperity characterized by the Pax Romana (Trebilco "Asia," 305). Augustus built a water system in Ephesus for, according to an inscription, "the people of Ephesus" (Crossan and Reed, 246). Part of this water system was an aqueduct of C. Sextilius Pollio built between 4 and 14 C.E., which, in part, remains standing today. The arches of this aqueduct were of dressed stone, and as for the abutments and superstructure, it was built of mortared rubblework (Ward-Perkins, 275). There was also a general increase in the number of donations and construction of public buildings during this time period (Rogers, 141; cf. Trebilco "Asia," 306).

Image scanned from John H. Vincent et al., Earthly Footsteps of the Man of Galilee (New York: Thompson Publishing, 1894), 2:325.

Magnesian Gate

This is one of the two entrances into the city. The road that led out of this gate would have connected travelers to Magnesia or Miletus. This gate was built sometime during the reign of Emperor Vespasian (69-79 AD).

The Tomb of St Luke

Is this where the beloved author of Luke-Acts has been laid to rest? It is very doubtful. There was some circular building that was later converted into a church. It was ascribed as Luke's tomb because there was apparently a bull carved into the door. According to the Anti-Marcionite prologues, which from date to the second to the fourth century, Luke "died at the age of eighty-four years in Boeotia" (Koester Gospels, 335).

State Agora (from the Odeion)

This structure was built sometime in the first century B.C.E., but at this location there have been found seventh/sixth century B.C.E. graves. The agora is roughly 520 x 240 feet. The following photograph was taken from atop the Odeion, which is on the other side of the Curetes street. At the northern side of the state agora was a triple-aisled and two-story stoa, which was sponsored by C. Sextilius Pollio and dedicated to Artemis, Augustus, Tiberius, and the people of Ephesus (Crossan and Reed, 248).

Odeion (Bouleuterion)

A boule was the ancient council, and so a bouleuterion is where this took place. An odeion, however, was a place for small concerts or other performances. This structure, which originally would have had a roof, would have served as both an odeion and bouleuterion (Ward-Perkins, 262).

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Tomb/Fountain of Pollio

This fountain was built for C. Sextilius Pollio in 97 C.E. He was the patron responsible for the aqueduct in Ephesus. There was a pond in front of the fountain, decorated with the Odysseus and Polyphemos statue group.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Prytaneion

The prytaneion was originally constructed in the third century B.C.E. It was later reconstructed during the Augustan age. Prytaneia were common in Greek cities (there are eighty-four of them to be identified as such). They were used for religious ceremonies and banquets. A prytaneion would also house the eternal flame of the city, and would be where the head magistrate, the prytanis, performed his duties.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Temple of Domitian

Though it is often called the Temple of Domitian, it is more accurately known as the Temple of Flavian Sebastoi. It bears an inscription dedicated to Domitian, yet it may have honored the entire Flavian family. Understanding the imperial cult sheds a lot of light on the context of early Christianity. The imperial cult thrived mostly in the East (hence why it had such an impact on Ephesus), and the West. Most of its early expansion was on the fringes of the empire, although it was not completely absent in Rome. Here are some significant works on the subject:

- Lily Ross Taylor, The Divinity of the Roman Emperor (American Philological Assoc./Scholars Press Reprint, 1931, Reprint 1988).

- S. R. F. Price, Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor (Cambridge: CUP, 1984).

- Duncan Fishwick, The Imperial Cult in the Latin West (Leiden: Brill, 1987).

- Richard A. Horsley ed. Paul and the Roman Imperial Order (Harrisburg: Trinity Press International, 2004).

Images property of Pitts Theology Library.

Memmius Monument

This monument was built during the Augustan Age, and it honored Memmius, the grandson of Sulla.

Gate of Herakles

The reflief work on these pillars dates to the second century C.E. The "gate" was relocated to its present location on the Curetes street in the fourth century C.E. Images property of Carl R. Holladay.

Curetes Street

This is one of the main streets in the city of Ancient Ephesus. Many of the sites for archaeological interest are found on this street.

Images property of Carl R. Holladay.

Fountain of Trajan

This was a large fountain or pool built in honor of Trajan (98-117). At this place, archaeologists have also found statues of Trajan's family as well as Dionysus, Aphrodite, and Satyr.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Temple of Hadrian

The Temple of Hadrian was dedicated to Hadrian (117-138) by P. Quintilius. Though the pediment has been destroyed, some of the archaeological features of the temple still stand out: the large Syrian arch, the Corinthian columns and piers, and the pedestals in front of the temple that later propped up statues of the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Constantius I, and Galerius.

Terrace Houses

Ephesus is also the home to a series of residential complexes from the first to third centuries known as the terrace houses (or Hanghäuser). The houses are built on a slope with narrow alleys separating groups of houses. The homes also shared walls with one anothr like apartment blocks (Ramage and Ramage, 305). [[It was the Ephesian version of Turner Village.]] They seem to have been influenced by both Greek and Roman style of houses (George, 18-19). Within these homes are well-preserved wall paintings that help to balance the overwhelming number of wall paintings found in Pompeii. These houses were occupied as late as the seventh century (Yamauchi Archaeology, 95). In addition to these terrace houses, a 20 meter by 20 meter peristyle house has been uncovered above the theater, which some have postulated was the home of the proconsul (Oster "Ephesus," 2:545).

Baths

These baths were built in the first century C.E., yet expanded in the fourth century. Baths were a very important part of Roman society. Here are typical components of Roman baths:

- Apodyterium = changing room

- Palestra = Greek style wrestling room

- Frigidarium = cold bath

- Tepidarium = a warm bath

- Caldarium = the hot tub

The Roman men would generally utilize the baths during the late afternoon, while conducting business and socializing with friends and patrons/clients. One would first enter the Apodyterium where they would change out of their clothes and prepare for the baths. Some baths were equipped with a Palestra for excercise and training. Some baths had separate bathing areas so that the women could utilize the facilities as well, but for those baths that did not have separate bathing areas, the women probably bathed between nine and three o'clock. Lucian (120–180 C.E.) describes a newly designed bathing facility in his day:

The entranceway is lofty and has a wide flight of steps which are low rather than steep, for the convenience of people walking up them. You enter into a very spacious hall which provides a large waiting area for slaves and attendants. To the left of this hall are rooms designed for relaxation, and therefore particularly well suited to a bath building—elegant, well-lit, and private rooms. Next to these is a meeting room larger than one normally finds in a bath building, but necessary for reception of the wealthy. Beyond this room are two spacious locker rooms and, between them, a lofty and brightly lit hall which contains three cold-water swimming pools. It is decorated with slabs of Laconian marble and with two white marble statues....

Upon leaving this hall, you enter into a large room which is long, rounded at each end, and slightly warm, rather than being confronted suddenly with intense heat. Beyond this room and to the right is a very bright room which is quite suitably arranged for rub-downs with oil. At each end it has an entryway decorated with Phrygian marble to provide access for those coming in from the exercise area. And then near this room is another large room, the most beautiful of all rooms, very well designed for standing about or sitting down, for whiling away time without fear of reproach for occupying your time most profitably. It, too, gleams from top to bottom with Phrygian marble.

Next you enter a passageway heated with hot air and faced with Numidian marble. It leads into a very beautiful room which is filled with bright light and resplendent with purple. This room contains three hot tubs. Once you have bathed, you don't need to go back again through the same rooms. Instead, you can go immediately through a small, slightly warm room to a cold room.

Every room has a great deal of sunlight coming in. In addition, the height of each room is of good proportion, and the width corresponds well with the length.... The cold room lies in the north part of the building, but the rooms that need a lot of heat are situated in the south, east, and west....

The building also has two privies and many entrances and exits, and provides two devices for telling time—a loud water clock and a sundial.

Lucian, The Baths 5–8 (quoted in Shelton, 313-314).

There is also a very interesting tradition via Polycarp about John in the baths in Ephesus:

There are also those who heard from [Polycarp] that John, the disciple of the Lord, going to bathe at Ephesus, and perceiving Cerinthus within, rushed out of the bath-house without bathing, exclaiming, "Let us fly, lest even the bath-house fall down, because Cerinthus, the enemy of the truth, is within."

Irenaeus, Adv. Haer., 3.3.4.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Latrine

The latrine was adjacent to the bath house.

Images property of Pitts Theology Library.

Hadrian's Gate

This gate stands at the southern end of the marble street. Based on its architectural decoration, it dates to the early second century, sometime during the Trajanic-Hadrianic period. The name "Hadrian's Gate" is indicative of its period, though it does not necessarily have a connection to Hadrian.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

The Library of Celsus

The great library in Ephesus is one of the most photographed structures in the city. It was dedicated to Hadrian, late in his reign. It is spectacular because of its use of alternation: it has alternating open and covered spaces, round and triangular pediments, projections and recessions, which are further intensified by the niches. The second photograph shows the ornate detail of the structure.

Gate of Mazaeus and Mithridates

Two freedmen named Mazaeus and Mithridates built this gate and dedicated it to Augustus in the first century C.E. The gate has the resemblance of a three-arched triumphal arch. Allegedly, there is a piece of graffito condemning those who urinated in that spot, even though it was right next door to the latrine! Note: there is no connection between this Mithridates and the one who had a stronghold against the Romans in Ephesus (88 B.C.E.).

Images property of Pitts Theology Library

Pavement Stone (Brothel Directions)

It was common for advertisements and messages to be inscribed into the ground. Here are directions to a brothel.

Image property of Carl R. Holladay.

The Theatre

The theatre in Ephesus is remarkable. More will be said about it in the next section because of its role in the narrative of Acts.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

The Agora

Ephesus, like every Greek city, had an agora. After a devastating earthquake in 23 C.E., the undertaking of the Tetragonos Agora had been initiated. It was later rebuilt in the third century C.E. (retaining its hellenistic style), and consisted of a colonnaded square with shops in the surrounding porticoes (Ward-Perkins, 285-286). This was the main marketplace in ancient Ephesus. The courtyard itself measured more than 360 feet in length.

Images property of Pitts Theology Library.

The Harbor Street (Arkadiane)

This is the street, or arcade, that led from the theatre to the harbor. It used to lead right into the sea, however, after many years of recession, the water is about two or three miles away. The collonade component of the street dates to the fourth century (Ward-Perkins, 286-287).

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Gymnasium

The Greek word gymnos means naked. Since participants would train and compete in the nude, the term gymnasion (Latin gymnasium) was appropriate. Gymnasia often contained an open courtyard called a palestra, which was surrounded by a colonnade. In some ways there was an overlap between the functions of a gymnasium and a bath. The gymnasia were also places of learning, where both boys and girls would learn to read and write in the rooms surrounding the palestra.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Church of Mary

It is not surprising to find a church for Mary since tradition suggests Ephesus is where she spent her later years. This church was constructed in the late fourth century, and was home to the Third Ecumenical Council in 431 C.E.

Image property of Pitts Theology Library.

Artemision

The temple to Artemis was the most important structure in the city, although it was separated from the city center by about a mile. More will be said about the temple in the next section because of its role in the narrative of Acts.

Image property of Carl R. Holladay.

Church of St. John

The church of St. John was built over the tomb of John. Though smaller churches were built on this site, this building was constructed in the Justinian Period 527–565 C.E.

Image property of Carl R. Holladay.