History of Finnish settlement

Finland: meeting place for eastern and western cultural influences

Rock paintings and animal ceremonies

Oral tradition

First literature references and mythological studies

Cosmology

The ancestor cult

Hunting rites

Gods and guardian spirits

The unlettered culture of the Finnish people was for the historians of the ancient world a complete terra incognita until Tacitus, in the year 98 AD, mentioned in his Germania a people called the Fenni, living somewhere in the northeastern Baltic region "in unparallelled squalor and poverty". The northern area referred to by Tacitus was at that time already inhabited by peoples of various ethnic and historical origin, and it is questionable whether the barbarians of whom he spoke were in fact the forefathers of the present Finns or the Lapps.

History Of Finnish Settlement

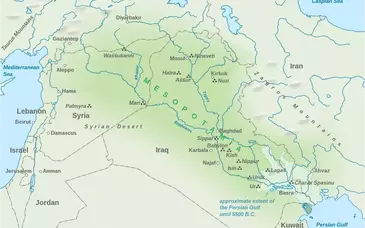

Recent archeological research findings prove that there has been continuous settlement in Finland since the mesolithic Suomusjärvi culture, i.e. for about 9,000 years. It is nowadays commonly agreed by linguistic researchers that a FinnoUgric or Uralic language had spread to Finland by the time of the neolithic comb pottery period at the latest (c. 4 200-2 200 BC). During the Iron Age (c. 500 BC-400 AD) five different areas of settlement emerged, cultural elements of which can still be discerned in modern Finnish society. The most important area was the coastal region from Porvoo to Vaasa. This area, called Finland Proper, witnessed numerous cultural innovations that gave Finland her own individual character. This was the nucleus area of the ProtoFinnic language, of folk poetry in Kalevala metre, of agricultural methods, and so on. It was from these new areas of settlement that the peasant way of life spread north and east and integrated the nomadic hunting and fishing communities. Numerous layers of folklore reflect the interaction of cultural phenomena from three ecological regions: the Arctic, the Woodland and the Steppe.

Finland: Meeting Place For Eastern And Western Cultural Influences

The position of Finland as the most northerly meeting point for eastern and western European cultural influences was already established by the Bronze Age, when the Scandinavians reached the southwest coast of Finland. The hunting and fishing economy continued in the central regions, this having been the predominant way of life of the early FinnoUgrians. Contrary to former hypotheses, the FinnoUgric peoples probably never had a common home in the region of the Volga. They inhabited far wider areas, from the Urals to the Baltic.

A nomadic way of life was a necessity imposed by their economy.

In the historical era Finland remained a crossroads for two cultures. Christianity came to Finland from two directions from the 11th century onwards. One was Karelia, which had in the Viking era been under the influence of the ByzantineRussian Church of Novgorod. In many periods of history the province of Karelia proved significant as a cultural bridge between East and West, and also between North and South. The position of Karelia between conflicting groups was not easy in the 16th and 17th centuries in particular, when Russia and Sweden were repeatedly at war. The people of Karelia were split by political, economic and religious disagreement and pushed the borders of the traditional Karelian way of life further to the east. The GreekOrthodox tradition, which had its roots in Byzantine culture, gradually became adopted as the religion of the Karelians. A sort of symbiosis developed that was quite the opposite of the western form of Christianity.

Three crusades were made to the southwestern part of Finland, in 1155, 1238 and 1293. Over the centuries a syncretistic religiousness emerged. Presentday life in both eastern and western Finland displays clear relics of a preChristian religion. In the Orthodox region it was still known as late as about 1900 for the head of the household to execute the traditional rites immediately after the Orthodox priest had blessed a new home; the purpose of the rites was to make the guardian spirits favourably disposed towards the new inhabitants.

Rock Paintings And Animal Ceremonies

Finnish rock paintings represent the philosophy of Stone and Iron Age man and his life as a hunter. The drawings on vertical rock faces reflect his world view, in which elks play a central role. Close on 70 % of the motifs in a total of 33 prehistoric rock paintings discovered in 1978 show elks and human figures. Comparison with corresponding material from north Eurasian hunting cultures indicates that the Finnish rock paintings are manifestations of animal ceremonies and the shamanistic tradition associated with them. This embraced the idea of souls in contact with one another. According to this both humans and animals had guardian spirits. These spirits were contacted in ceremonies before and after hunting. The shaman, on behalf of the community, conducted a ceremony during which he fell into a trance and became his own guardian spirit, his alter ego, then seeking the guardian spirit of the game in question. Every species of animal had its own guardian spirit, which had to be consulted by the shaman in order to ensure success in hunting. The purpose of the ceremony after the hunt was to guarantee a sufficient supply of a particular game species in the future too, by returning a game animal to the keeper of its species.

The points at which game was most easily accessible can be concluded from the location of the rock paintings, along the waterways. The paintings referred to sacred places at which it was possible to contact the keeper of a game species and to request success in the hunting of this species. Similar to these are e.g. the sacred places of the Lapps with their seita idols. The rock paintings with elks depict the guardian spirit and the keeper of the elk. Pictures might be painted before the hunt, to guarantee success, or afterwards, to guarantee future luck in hunting. The anthropomorphic figures could represent a shaman, a person capable of contacting the spirits. Other pictures, different living creatures and abstract symbols represent the shaman's animal helpers.

Oral Tradition

The basis of folk material on Finnish mythology and worldview is to be found in the old Finnish poems. Inspired by the epic the Kalevala, systematic collection was caried out in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Between 1908 and 1948 material from the archives was collected in the 33 volumes of the Ancient Songs of the Finnish People. Other folk material, either published or in the archives of the Finnish Literature Society, consists of beliefs, legends, myths, all in prose form, and the poetic genres of incantations and laments. These genres of the oral tradition contain mythological motifs, from which it can be concluded that they extend back to the ProtoFinnic era. The epic poetry has thematic corespondences with many old myths of other peoples. Of greatest significance here is a cosmogonic myth in the song of the creation of the world, in which the hero, Väinämöinen , enters the primaeval waters and then creates the cosmos from the broken pieces of an eagle's egg. Variants of this song contain many other cosmogonic motifs such as the forming of the primaeval seabed and the freeing of the sun and the moon from the belly of a fish. The demiurges and heroes of the oldest myths of origins of the ProtoFinnic people were theriomorphic. In later periods of cultural development they were replaced by anthropomorphic equivalents, the most important being Väinämöinen and llmarinen. Väinämöinen is described in folklore as the patron of marriage and as a shaman who achieved his goal by ritual techniques. In llmarinen two layers of tradition are combined: the older represents him as a deity, the younger as a cultural hero, a smith who forged the firmaments.

Incantations are another rich source of Finnish mythology. At healing ceremonies the disease is diagnosed by reverting to its origins, from which all present forms are derived.

The origin of convulsions, for example, is an incantation that tells in the prologue of a mighty oak tree that stretched up to heaven, masked the sun and the moon and restricted the free movement of the clouds. A woodcutter is required and sought in heaven and earth. Finally a dwarf is found who fells the tree with a single blow, and the light of heaven shines again. This myth was used in healing ceremonies because of the results of the felling: convulsions spring from the splinters that fly about as the oak falls into the sea. The oak in the prologue to the incantation symbolises the cosmic tree, the tree of life or the column through the centre of the earth.

First Literature References And Mythological Studies

The first literary source of Finnish folk religion was by the Finnish Lutheran reformer, Bishop Mikael Agricola (1508- 1557), who in 1551 published a translation of the Psalms of David. Appended to the foreword to this book is a short list of the deities worshipped by the Finns in the regions of Häme and Karelia. The list contains eleven deities from Häme under the subheading of piru, the devil and twelve Karelian gods. The Home list appears in the light of subsequent tradition to be thoroughly heterogeneousit contains cultural heroes (Väinämöinen llmarinen), the guardian of the home ( Tonttu), wealth ( Kratti), the forest ( Tapio), and water (Ahti). Also included are spirits belonging to the realm of etiological tales, e.g. the ghost of a slain child (Liekkiö). There are two spirits of nature, those of the forest (Hiisi) and of water (Weden emä). The other ten deities belong to the Karelian calendar, i.e. they are actualised in the domain of a given occupational group in given situations, such as at the beginning or end of a given period of time. The deities that belonged to the preChristian tradition were the supreme god Ukko, his wife Rauni, and above all Kekri, whose feast was celebrated at the end of the agricultural and cattlebreeding year. The seven other names on the list are of Byzantine origin, but free from their Christian connotations. They were saints of the Christian church year that had lost their original character to such an extent that Agricola took them for heathen deities.

Agricola's list of deities was not only the most important but for two hundred years also the only literary basis for Finnish folk religion . Following Agricola it was 1766 before any new material came to light, when Henrik Gabriel Porthan, professor of rhetoric at the University of Turku, published the first volume of his work De poesi Fennica. The influence of Porthan is also recognisable in the dissertation by Kristian Lencqvist entitled De superstitions veterum Fennorum theoretics et practica of 1762, and in Kristfrid Ganander's Mythologia Fennica of 1789. In his dictionary Ganander lists all Finnish and Lapp mythological names and concepts in alphabetical order. This work also has explanations, so it replaced Agricola's list as the basic source of preChristian Finnish belief and became the most important work before the publication of the Kalevala, the masterpiece by Elias Lönnrot, in 1835.

The Kalevala can be considered from three angles. To begin with it is a portrayal of Finnish mytholoy through the epic poems collected by Elias Lönnrot; secondly, it represents the mythological dream of the Finnish people, and finally it is, in the compilation of Elias Lönnrot, a statement of the worldview of the Finnish people.

Cosmology

The Finnish cosmology contained in sources displays the symbolic structure characteristic of most northern folk cultures. The region inhabited was regarded as an island surrounded by a stream. The earth was round, and above it stood the mighty vault of the heavens. The circular stream surrounding the world was regarded as the border between the living and the dead. The idea that the dead must cross this stream in order to reach Tuonela, the kingdom of the dead, is not, however, of Finnish origin and is part of the mythical tradition of the eastern cultures. According to the belief of the northern peoples the dead cross this stream in the far north. There lies the village of Pohjola with its iron gate, on the other side of the terrible waterfall of Tuonela, which turns everything upside down. Tuonela is thus a reversal of the world of the living. Before the gates of Pohjola lies the intersection of heaven and earth. This intersection, opposite Pohjola on the south side, was the realm of the dwarf lintukotolainen (dweller in the land of birds) or taivaanääreläinen (dweller of the horizon). This was also regarded as the destination of migratory birds.

The cosmos was divided into three zones: the upper world, the middle world and the underworld. This tripartite structure is one of the oldest north Eurasian folk beliefs. The three cosmic planes were joined together by the cosmic tree, the cosmic column or the cosmic mountain located in the centre of the world. The top of the column was attached to the North Star, about which the heavens rotated. The Finns also likened the North Star to a hinge and spoke of the "heavenly hinge", likewise the "north pin", the "celestial keeper", the "pole star" and the "heavenly pole".

The Ancestor Cult

The worship of dead ancestors was a fundamental part of Finnish folk religion. Its basic features were also evident in many other traditional acts, in the calendar rites, the Kekri festival celebrated on around November 1, and in the various rites of passage.

Uno Harva writes of the social role of ancestors in peasantagrarian society: "There are countless examples to prove that those who had passed on into the underworld played a particularly important role in the beliefs of the ancient Finns. The object of worship proper was not however, the dead person himself but all the dead of each individual family, whose descendants were entrusted with the sacred duty of continuing their work and fulfilling their wishes. This custom lay at the base of the ancient Finnish community. The dead were the guardians of morals, the judges of customs, and they maintained the order of society. In this respect not even the god of the upper regions could compete with them." (Harva 1948, 510-511). The Finns conceived of the family as a unit, regardless of whether its members resided on earth or in the underworld. The vital point of burial customs was to afford the dead the rites of separation, transition and incorporation into the fellowship of the family dead, and furthermore reorganisation of the remaining community.

The dead had a dual function in ancient Finnish society: they were cared for so that they would protect and watch over the prosperity of the family, but they also aroused fear, because it was accepted that they would punish anyone who neglected the rites or who did not conform with the customary norms. In former times the worship of the dead used to take place at sacrificial trees or stones. The first fruits and the first newborn cattle would be sacrificed to them as their share of the annual harvest. The sacrifice was in the nature of an obligatory offering. The family also organised the burial ceremonies and the periodic memorial festivals.

There were, however, major differences between the Lutheran and the Orthodox regions. In the Lutheran region the final departure of the dead took place at the burial on the third day after death. No memorial feasts were held.

In the Orthodox region of Karelia the old tradition of holding memorial ceremonies in the cemetery continued until the 19th century. Death was followed by a critical period, until the kuuznedäliset, the "sixweek festival". Six weeks after the death of a pokoiniekka (a person not yet incorporated into the fellowship of the dead) the family would by night hold the "final wedding", granting the deceased his or her new status among the nonliving members of the family. In addition there were two calendary memorial feasts. One was in spring, on the second Tuesday after Easter and was called ruadintsa. The other was called muistinsuovatta (Memorial Saturday) and took place in the autumn, on the Saturday before October 26. One special memorial feast was the piirut. This was arranged by the family in honour of a very important ancestor, such as a former head of the family. It was a general feast for the whole kin, it was not tied to a specific date and would be held whenever the relative felt it was necessary.

One special group of ancestors in Finnish folk religion consisted of those who had no place at all in the community of the dead. These were called sijattomat sielut (restless souls). Their restlessness was caused by inadequate or missing rites in preparation for their journey to the land of the dead. It was believed that they haunted the house, for no fault of their own or because they were guilty.

Huntig Rites

The first description of a Finnish bear feast was given by Bishop Isak Rothovius, who founded the University of Turku in 1640. He criticised the Finns for their myths and said in a sermon: "When they kill a bear, they hold a feast, drink out of the bear's skull and imitate its growling in order to ensure successful hunting and plenty of game in the future." The sources providing information about bear feasts contain detailed descriptions of all the rituals and epic poems and incantations referring to the mythical origin of the bear. These etiological poems and incantations were recited either during the bear feast or when the cattle were put out to pasture in summer. In the latter case the aim was to protect the cattle from the bear.

According to one description from the 17th century the bear feast consisted of three consecutive acts: the killing of the bear, the feast proper (karhunpeijaiset or karhuvakat, i.e. a beardrinking feast in honour of the slaying of the bear), and the bear skull rite. These acts were symbolic for the death of the bear, its burial and its resurrection. Hunting rites have structural similarities with the cult of the dead, in which the emphasis lies on the preservation of the existing social order and its institutions. Like the death ritual, the bear ceremony was also called a "wedding", kouvon häät. During the cult drama a bride was chosen for a hebear, a bridegroom for a shebear.

Gods And Guardian Spirits

Finnish mythology has no divine hierarchy, although incantations address Ukko as the supreme god in heaven. Ukko was primarily the god of thunder, as is indicated by the Finnish word for thunder, ukkonen. In his list of deities Agricola gives a valuable indication of the cult of Ukko: "And when the seeds had been sown in spring, a toast was drunk to Ukko. This was to seek Ukko's bushel both maidens and women drank freely. Many disgraceful things were performed, as could be both seen and heard." The 17th century report thus gives an interpretation of the reference to the "holy wedding" that is missing in Agricola.

The tietäjä, the seer corresponding to the shaman of the hunters in the agricultural community, called on Ukko not only as the god of rain and storm. Ukko was also called on in many difficult situations, such as confinements, curing the sick, when luck in the hunt was vital, and so on.

Another deity was llmarinen, who according to Agricola was the ruler of peace and the weather. The name llmarinen is a derivative of the word ilma, meaning weather or air, in some diaiects also storm, thunder storm, hurricane and sky. According to one report from the 17th century llmarinen was the god of wind. This report is the oldest evidence of llmarinen, who can be traced back to the Perm god Inmar, the god of the Votyaks. The syllable inm in his name is the etymological counterpart to the Finnish ilma. As has already been mentioned, folklore describes Ilmarinen as a cultural hero and also as a smith.

Finnish folk belief refers to many local guardian spirits called haltijat. The word denotes male or female guardian spirits in the role of occupants, owners or rulers. Every guardian spirit normally possessed a special domain over which it had command and from which it also took its name, such as forest spirit. The guardian spirits of the various buildings and localities watched over their domain and the economic or other activities conducted here. The domain of the house spirit embraced the house and yard, the spirit protecting the cows the cowshed, the riihi spirit the threshing and drying sheds, and so on. The specification of the roles and the allocation of the fields of responsibility attributed to the spirits was continued in the Catholic calendar of the saints. As patrons of various economic activities the saints entered into the former system of guardian spirits.

Written for the Ministry for Foreign Affairs by Professor Juha Pentikäinen, University of Helsinki

The views expressed in the article are solely the responsibility of the author